Elaine McMillion Sheldon Documents the Dreams and Myths of Appalachian Coal Country

Published: August 09, 2023

Published: August 09, 2023

Words: Elaine McMillion Sheldon

Words: Elaine McMillion Sheldon

Published: August 09, 2023

Published: August 09, 2023

Words: Elaine McMillion Sheldon

Words: Elaine McMillion Sheldon

Fred Powers talks to students about his time in the mines.

The film started in 2019 by documenting coal culture, seen through coal dust runs, pageants, coal shoveling contests, and coal education in the classroom. Some of these things have been around since I was a kid in the coalfields. Co-Producer Molly Born and I sought these rituals and traditions out to document a living archive. One of our very first shoots for this film was in a classroom with kids. Fred Powers, a retired miner, told stories of his time in the mines, labor disputes, and fatalities. He had no “kid filter” to his message about coal — it was neither pro or anti-coal, it was simply his story. Fred impressed us with his ability to walk the fine line of honoring the past, while calling out the injustices. The kids impressed us with their attention, curiosity, humor, and enthusiasm. It was clear, when the students asked “what is that?” as Fred held up a piece of coal, that this story of coal was not one of their own making, but instead one that was being handed down to them. As we documented the coalfields, it quickly became clear these coal-related rituals were dying traditions. Many of them were traditions born out of people’s fears of “the king” dying. So I started to ask — what new rituals do we need in life and in film to help us live? This led us to think more about the already-blurred lines between myth and reality, of the power and influence of coal, when it comes to life in the coalfields.

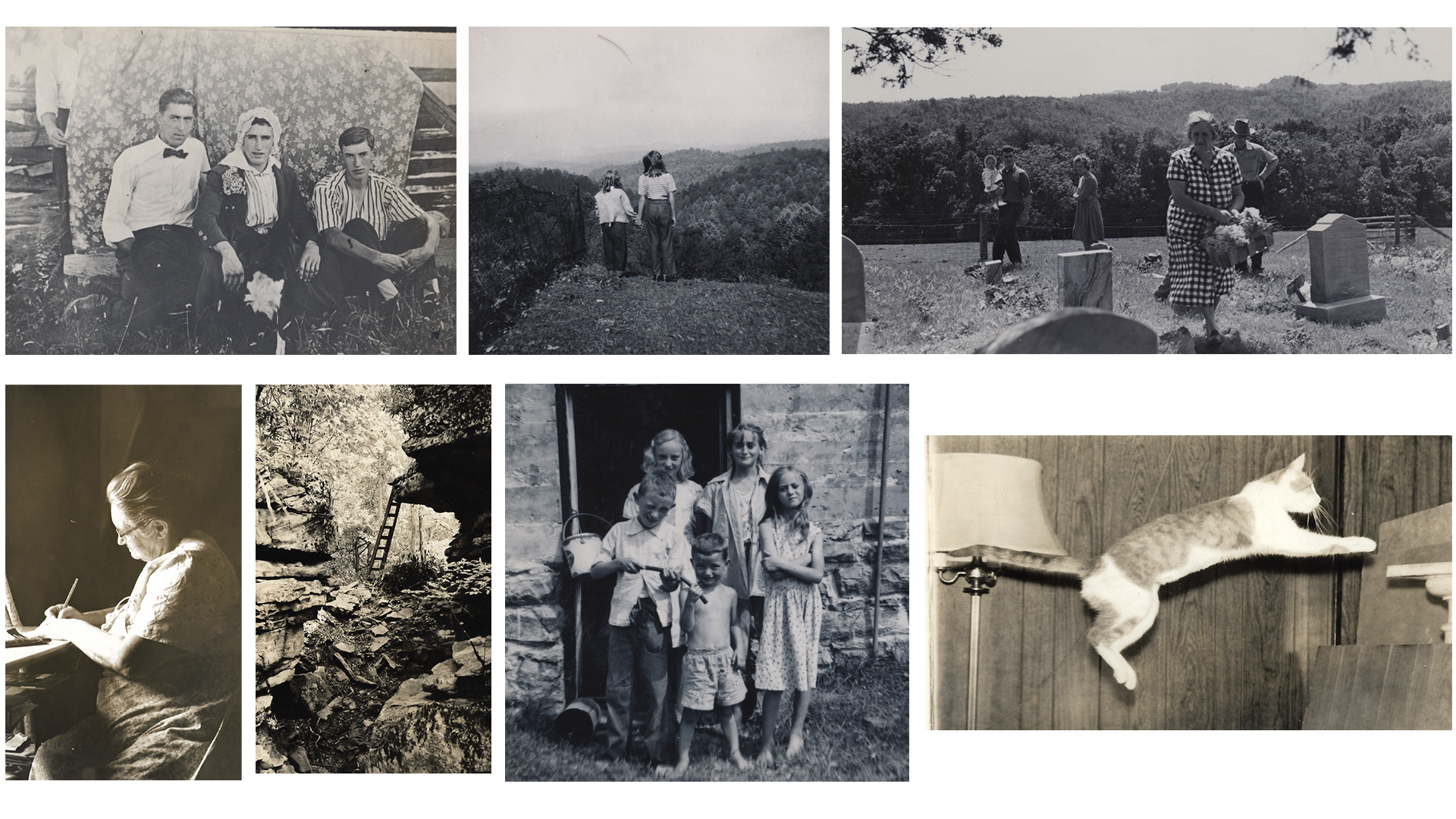

Elaine McMillion Sheldon’s family archives.

Documenting coal culture wasn’t enough. It was the seed for the film, but not the flower. The idea, the seed, needed patience and time. It needed nurturing. Oftentimes our first ideas are too obvious, but this process of germinating is not a passive experience. It is one I lost sleep over. Watering it daily through sitting down and forcing myself to write. Through digging through the archives. Through conversations with producers, Shane Boris, Diane Becker, and Peggy Drexler; editor, Iva Radivojević as well as my partner and director of photography, Curren Sheldon. Through relearning my own history and seeing the blindspots. Through letting go of what was acceptable in nonfiction storytelling, and making room for anything else. I looked to other traditions — family archives, poetry, folklore, magical realism, ghost stories, fables, dance and movement, the land itself, and sound art, among other cinematic tools — to help guide the final language of the film.

My own family archives began to be a portal in which I could imagine new and old narratives colliding. My family has been in Appalachia for nine generations. My great uncle, Roy Russell, documented the mundane and surreal moments of his life in the mountains. Moments of kids at play, of my great grandmother writing letters, of the first miners in my family, of decorating graves at the family cemetery, and of ladders that led to unknown caves. In the end, I learned that I needed to break open my ways of working. Of relearning how to tell stories, how to add more play into my nonfiction, to get to a deeper, more internal truth beyond an observed truth. My community is in need of grieving as a way of processing the impact coal has had on us. But I also was in need of this. I used this film as a way to grieve with my community and family.

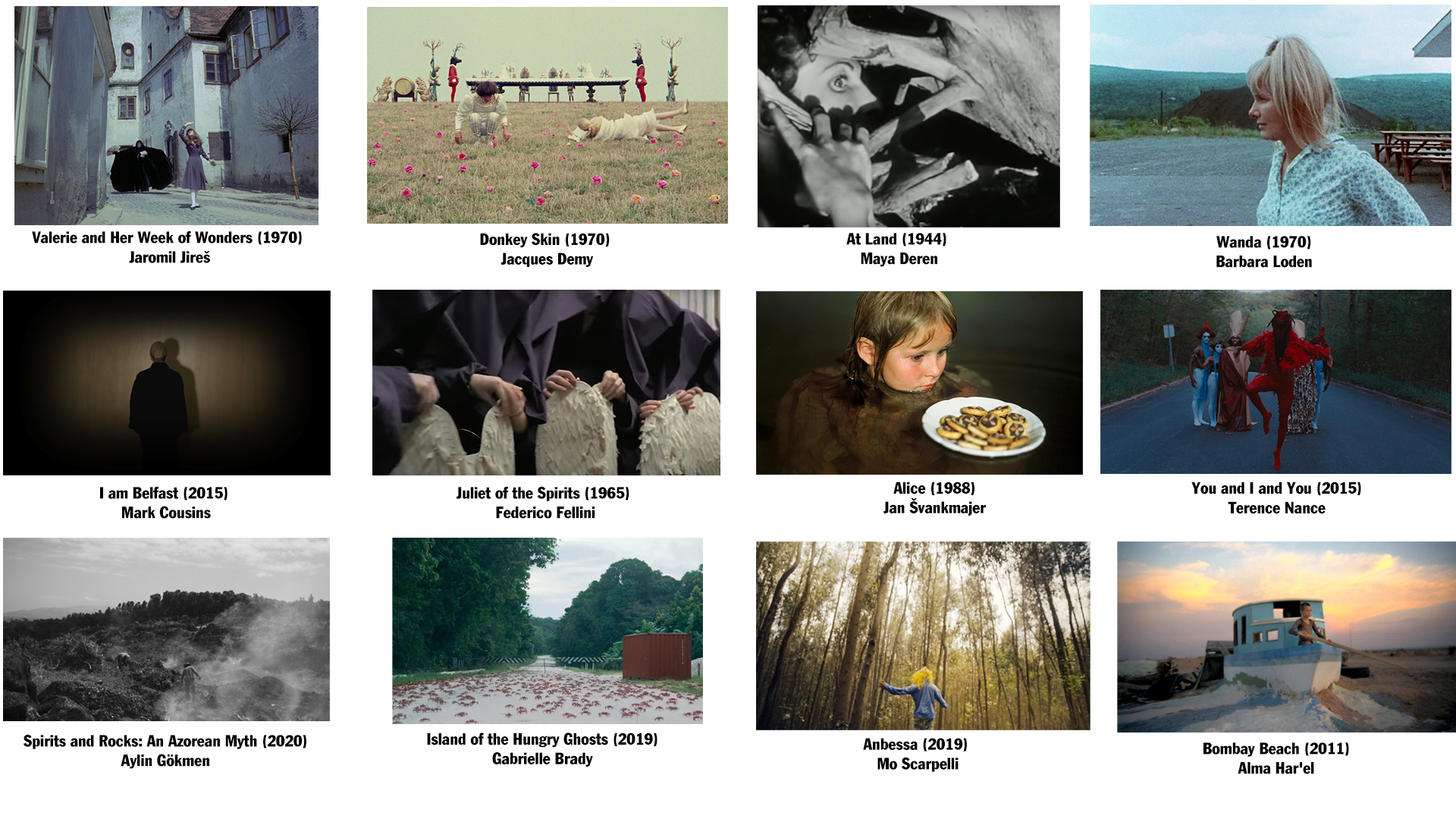

Films that inspired the magical thinking of King Coal.

I began filming King Coal in 2019, but when COVID-19 kept us at home, I had time to start thinking more about the goals of this film as a piece of cinema, not just from a traditional documentary impact point of view. I sought out films that helped me break open the ways I had been telling stories. Above are some images from films that inspired my thinking behind King Coal. These are films that explore the myths of places, the dreams of children, hauntings and ghosts stories, dance and movement, surreal sound design, use voice-over narration as a guide, feature raw vérité moments, rely on mosaic structures, center children and/or women, employ wardrobe and production design as a form of storytelling, explore Afrofuturism and magical realism, use editing to create new worlds with a single cut, and where metaphors and symbolism are at the center of plot. There are many more films to be listed (“Badlands” by Terrence Malick also comes to mind when writing the voice over narration), but it felt like a very important part of my process to broaden my reference points outside of documentaries. I aimed to tell a story that was felt, but not always seen. That required me to employ cinematic tools I had never used before in vérité filmmaking.

Read Elaine’s full list of films that inspired thinking in King Coal here.

Director of photography, Curren Sheldon, and director, Elaine McMillion Sheldon, with their 3-month old baby while filming King Coal in Thurmond, West Virginia.

The writing process first began before filming started. I found myself drawn to a form of creative nonfiction that blended personal story with folklore. As we began to film King Coal the writing evolved and became a reaction to the footage itself. Some of the writing digs beneath the surface of what is being seen, like a coal dust 5K, to illuminate the psychology of coal as a cultural touchstone. My goal was to tell the truth, but without complete condemnation. Towards the end of the film the narration shifts from “I” and “me” to “we” and “us.” This collective sense of identity carries through to other aspects of the film. The script poses more questions than answers, something contributing writer and editor, Iva Radivojević, encouraged.

In the middle of production, I gave birth to my first child. Having a child really put into perspective the story I needed to voice through this film. I asked myself what I wanted to communicate about the history of Appalachia and the fading role of coal to the child I was bringing into the modern world. It became very important that this film didn’t just replace the negative ideas of Appalachia with beautiful ones, but instead allows the pain and strength to swirl around in order to allow for a slow absorption of contradictions, irony, and imagination. The process of making this film required a level of vulnerability and personal excavation that was challenging, but speaking to the next generation gave me courage. My initial resistance to being the narrator faded away as the team and I recognized that it was my voice that was most true to the writing, which is not always first-person, but always personal. Hats off to my contributing writers, Shane Boris, Logan Hill, Iva Radivojević, and Heather Hannah, who read countless drafts and edited for clarity, rhythm, and pacing.

Lanie Marsh dancing at Blenko Glass in Milton, West Virginia.

The film is a documentary that blends fictional and fable storytelling elements to tell a different story of coal. One way it does this is by centering the story on two West Virginia girls, Lanie Marsh and Gabby Wilson, who were cast for the roles at local dance studios. Some of the scenes they are featured in are real-life moments, like the West Virginia Coal Festival in Madison, W.Va. In those scenes, Lanie and Gabby were placed there to show what it’s like to be a kid, but the things they say and do in them are completely unscripted and unprompted. Other scenes, such as those featuring the girls dancing in front of coal piles or in surreal landscapes, were set up for the purposes of the film. But never were Lanie and Gabby given a script to read; they were asked to be themselves in every scene.

Behind the scenes at a funeral held for King Coal.

This is a film that blends vérité scenes with imagined scenes where real people, non-actors, were asked to just go about life in front of the cameras. But the scene itself, in the case of the funeral as pictured above, would not have existed without the framework of the film. Other scenes were purely natural, with us filming live events but with two young girls —dancers with coal family connections that we cast— just being kids in the moment. It was a constant recalibration and humbling experience to dream big, fail massively, and then get back up the next day and try again. This type of filmmaking required everyone on our team to think on their toes about how to best capture the magic of real life and always ask how this might work in our overall narrative.

King Coal is whole-heartedly a product of taking creative risks. We filmed this over three years and we were led from shoot to shoot based on reactions and creative impulses of our team and Appalachians we filmed with. Some ideas for shots and scenes came to me as a single image from my imagination, or a memory from childhood that I wanted to recreate. Others were spontaneous ideas that popped into our minds while being immersed in the environments we filmed in. The entire act of filmmaking and creating this film was a call and response between our team and the land and people we were filming. Much credit goes to our small, but mighty, on-the-ground producing team – Diane Becker, Shane Boris, Molly Born, Clara Haizlett, Curren Sheldon, and Elijah Stevens – who took my craziest ideas for scenes like king coal’s funeral, and made them a reality.

Bobak Lotfipour talks about his work on King Coal at San Francisco Film Festival.

Composer Bobak Lotfipour and I worked together to dream up a rich, challenging musical landscape that represented both the beauty and pain of the region largely through over 20 percussive instruments: drums, bells, crystal bowls, and playing non-traditional objects, such as sheets of metal. We sought to create two worlds for the music. The coal world being machine-driven, electric, with bass and darkness. The film in these moments has deep rumbles of uncertainty; the oppression that living in a boom-and-bust economy creates. In the non-coal scenes our palette was less mechanical; more human, animal, and textured. These natural sounds, including human whistles, were still mysterious and not too sweet. We sought a balance between the images and sound, imbuing calm visuals with an eeriness and mystery in the music. The musical landscape reflects the film’s focus on a community on the brink of change, with all its uncertainty and all the fears and joys.

Listen to the soundtrack here.

An ambisonic recording device built by sound recordist, Billy Wirasnik.

Our sound mix team at Signature Post was led by Alexandra Fehrman (CODA, 2021; Everything Everywhere All at Once, 2022) who supervised the incredible team: re-recording mixer, Tim Hoogenakker; sound designer, Benjamin L. Cook; dialogue editor, Christina Chuyue Wen; and foley services by Post Creations. The sound mix hinged on the emphasizing the lush environments captured by our production sound mixer, Billy Wirasnik, who recorded an incredible library of ambisonic nature recordings —birds, crickets, owls, thunder, wind, rain, rivers, creeks, forests— over the course of several years of production. We also worked with breath artist Shodekeh Talifero, who with his own body and voice made the sound of thunder, ocean waves, crickets, wind, whistles, and many other sounds. We recorded his session in a moss-floored, dense forest in the Allegheny Mountains (hats off to associate producer, Clara Haizlett, for finding this perfect outdoor sound studio). His sound art and human breath is used throughout the film as transitions and as a motif to explore the new life the coalfields are embarking upon. Sound, in addition to music, plays a key role in the film’s magical realism.

Beyond financial support, Creative Capital has helped build an ecosystem around me. Being a part of a community of talented artists has provided much inspiration. The mentorship and advising has helped me articulate my ideas more clearly.

I hope audiences can appreciate the ways we are pushing the boundaries of nonfiction to get to an emotional truth. To make a film that is experiential —calling upon all the senses, to tell a deeply felt, and true, internal story of identity and belonging. Maybe more than ever, I believe in the power of hopeful and future-forward stories; stories of reconciliation and cinema as a form of processing grief and change.

Catch King Coal had its NYC premiere at DCTV Firehouse Cinema in New York City from August 11—August 17, 2023. See where you can watch the film here. Watch the trailer for King Coal below.

Elaine McMillion Sheldon

Elaine McMillion Sheldon

Elaine McMillion Sheldon is an Appalachian-based filmmaker who explores challenges in American society and its effects on people.