Percival Everett Questions How We Trust Narratives in His New Novel, Telephone

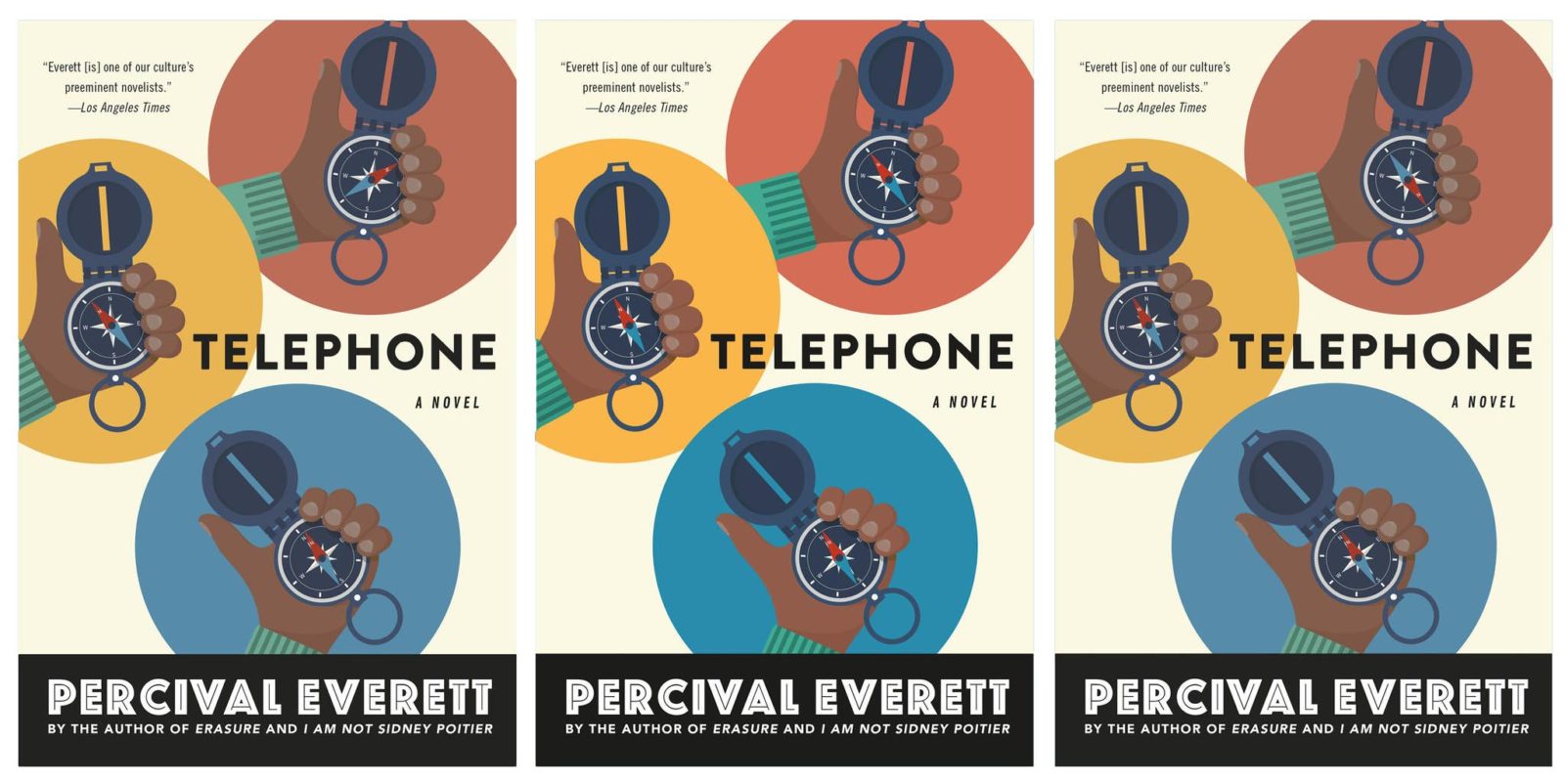

How often does a reader’s understanding of a book line up with the intention of its author? Percival Everett has a history of using his novels to play with the writer-reader relationship, but takes it to an unprecedented level in his Creative Capital Project, Telephone, a new novel published by Graywolf Press. The book tells the story of Zach Wells, a geologist who, after learning of his daughter’s diagnosis of Batten’s disease, goes on a series of adventures to save a group of women in New Mexico that he believes is sending him notes in used clothing he orders online. But readers may disagree on certain details about the book—that’s because Everett actually wrote three versions of the novel, all with slight variations, from the colophon and cover all the way to the conclusion.

We spoke to Everett over the phone just after the publication of the book.

Alex Teplitzky—I’m curious to know how you describe the book when you tell friends or family about it?

Percival Everett—Hm, well, I guess the answer to that is I don’t [laughs].

Alex—Or, how would you explain it to someone who didn’t know about it?

Percival—One of the reasons I continue to write is the exciting part of hearing how people read my writing. When I write a novel, someone will have a theory about what it means. They will say it, and I won’t recognize it. I do suffer from a kind of work amnesia, but even when I do remember, their reading is so different from what I meant. I realized long ago that what I mean really has nothing to do with the work of art. The circuit is not completed until the reader comes to the work and does the readerly work of constructing the meaning.

We always talk about the intention of the author—well, I think there’s something to be considered called the intention of the reader. We read because we bring certain things to a story, and when we bring those things, we create meanings different from anyone else. My interest is not in the intention or the authority of the artist or creator, but in the intention and the authority of the reader.

Alex—The reason I ask that question is because I was curious to know whether you introduced the book through the plot, or the project in general—of three book versions in one. I was introduced to this book through the panel selection for the Creative Capital Awards. Your application came up for producing three versions of one book. It was one of those projects that generated a lot of discussion, and it was so secretive. There was a big conversation about whether it was even possible. You don’t often hear people discuss whether something is possible when it comes to books.

Percival—Yeah, I wondered that myself. And I wondered whether, before Graywolf agreed to do it, whether the idea was one that any publisher would seek out.

Alex—So I’m interested to know how you thought writing these three versions of one novel would play out. You have a history of playing with the idea of writing and reading in a lot of your novels, so I think this idea about the reader’s intention that you mention is a natural extension of your work.

Percival—I think that’s probably true, although I wouldn’t have known that until it happened. Quite honestly, and quite literally, this is an experiment. I didn’t have a picture of how it played out. The reveal was supposed to be different from the way it’s actually happened because of COVID, but I don’t know how we were going to do it finally, anyway. I wanted to see how different reviewers and readers dealt with disagreeing with each other.

Of course, that window has now closed—that won’t happen, but that doesn’t mean there can’t be conversation about that. I was curious how book clubs might respond to the work without the knowledge that they were reading different stories.

Alex—Right, it’s interesting to think how in book clubs, there are discussions where one person says “I saw the work like this,” and someone else says, “that’s not how I saw it at all. I think what the intention here is…” It would be interesting to see those conversations, but don’t they happen anyway?

Percival—Well, not to the extent where your evidence for saying that is not in the other person’s book, and that was what I was curious about too. In the face of someone saying, “but she says on page 57…” and someone else says, “No she doesn’t!” Those were the conversations that I frankly miss now, but it’s ok.

Alex—I read that you did different sets of research for different books. I had imagined that the books would be only slightly different, so I was surprised to hear that you had taken completely different research trips.

Percival—It all comes together. The books are not that different. There are changes in language, and changes in some events. Two might be the same in one place, and a third might be different, or all three might be different some place else. You would never think you were reading a different book. They do end differently, but with the same people in the same circumstance.

That was one of the more fun parts about this. My work is always so solitary, and to do this with the people at Graywolf was a lot of fun. In fact, the title came to me in a meeting with them. I was in Minnesota, and I went to a meeting with Steve Woodward and some of the other staff, and I wasn’t happy with the title. The title was, at that point, Said The Wren, and I wasn’t happy with it. All of a sudden, Telephone popped out. Whether that’s the best title, I don’t know, but it worked for me and for them because it really has no connection with the story, but with the project.

Alex—I’m thinking about how in fiction in general, people tend to read it as nonfiction. A lot of times people try to read fiction as biography or autobiography, even though it’s clearly fiction. Were you thinking of that as well?

Percival—I wasn’t thinking about that, but you’re right—that’s a pretty amusing thing that people often do. I have a novel called American Desert in which the main character in the first couple of pages, his head is severed from his body in an accident and is sewn back on and the novel continues. I’ve had people ask me if that’s autobiographical.

Alex—Oh, wow really?

Percival—Yeah, that happens, but it wasn’t in my thinking. Real readers of fiction—and my audience isn’t incredibly wide, but they’re very sophisticated, it seems. They’re smarter than I am, I know that. They would never make that mistake.

Alex—How does your research influence your writing?

Percival—Most of it was understanding the landscape in which the last third of the novel happens, and also a trip down to Ciudad Juarez where I talked to the police of the murders of all of those women. I made several trips.

North New Mexico is a state I know very well, but I don’t know Southern New Mexico all that well. So, I had to work on that. I ended up crossing the border a bunch of times not knowing exactly what I was looking for, but just stepping across the bridge in El Paso.

I did my usual academic research, though not as much as I have, on paleontology and geology. It doesn’t really come to the book, but I find it necessary to assume the identity of my character.

Alex—In the books I have read of yours, like So Much Blue and I Am Not Sidney Poitier, you slip back and forth between the identities of your characters so well that I was fascinated to learn about the research aspect of the novel.

Percival—Yeah, I always do. Writing books for me is an excuse to study. I have a novel Watershed—I read 25 or 26 books on geomorphology and hydrology, and actually did a few months of field work with a hydrologist. There’s not a lot of hydrology in the book, but to understand the character I felt I had to do that.

“You can look at my books and realize fairly quickly that this man does not do this to make money. I just want to make books, and I want to learn something when I’m doing it, and I learned a lot doing this.”

The research I didn’t have to travel for—I do play chess, but I’m not a great chess player at all. I had to study a bunch of chess games to find one that did what I wanted it to do. That’s hard to explain, but that is work where often it does something for me, and not for anyone else. So there are alterations in the moves of a very famous chess game. That’s kind of my private language inside the text.

Alex—I’m also curious about the character’s daughter who has Batten’s disease. I met a boy who has Batten’s disease recently. Is it something personal for you?

Percival—Batten’s disease is seldom fatal in adults, and almost always in juvenile cases. I don’t remember how I got to it, but it was the idea of dementia setting in—the idea that this family would have to lose their daughter twice, as we do with our loved ones who have Alzheimer’s: they’re not who we know when they are still with us. More importantly, they don’t know us. I was taken with that idea.

Alex—My grandmother is going through that now. The weird thing is that it’s not the person I remember, but now it is, so it’s a strange thing to deal with.

Percival—They have these windows. I don’t know if you have experienced this. They have this 15-second period of lucidity where all of a sudden they are back, and then it’s gone. I don’t know if there’s a much better lesson about how to live than to see that happen.

Alex—Yeah, that’s interesting. I’m curious how the Creative Capital Award was helpful to you.

Percival—The support has been great. It allowed me to make more trips than I would have normally been able to take comfortably, and that was great.

But also—I don’t even know if I can explain it because again, I work in such a solitary way, and I have no business sense at all. I don’t even know how to talk about marketing or anything, but the presence of the staff has been so supportive. It was an attitude from them that I found that helped me get through the work because it was really hard to write these three books. When I write books, I never know if I’ll be able to write another book when I finish. But there were times when I was working on these three that I thought I would have to find another line of work. I have to say the emotional support was really helpful. The fact that they, like Graywolf, were willing to take a chance on an experiment just renewed my faith in art.

You can look at my books and realize fairly quickly that this man does not do this to make money. I just want to make books, and I want to learn something when I’m doing it, and I learned a lot doing this.

Percival Everett with his pet crow.

Alex—Just one last question I have to ask: whenever I research your name online, I find this photo of you with a crow on your shoulder. What’s the story with that photo?

Percival—That was my pet crow, Jim. He was a rescue. He fell from a nest. I raised him for a couple of years. I kept wanting him to fly away and have a crow’s life, and he finally did when I wasn’t there. Crows are really monogamous. He wouldn’t let my dogs come near me, or anyone come near me. He would just scream at them if they did. As much as I loved him, I would never have another crow for a relationship—it was too intense.

Read more about and purchase the book, Telephone, at Graywolf Press.