Jim Findlay Brings Bruce Haack Back From the Dead with “Electric Lucifer”

Even if you’ve never heard of the electronic musician Bruce Haack, there’s a good chance the songs you listen to have been influenced by him—he did pioneering work in the ’60s and ’70s on vocoding, autotuning, loops and synthesizers. Now, Jim Findlay’s Creative Capital Project, Electric Lucifer, pays tribute to Haack with an electronic rock opera that will premiere at The Kitchen. The live performance is inspired by Haack’s album of the same name, as much as it is an exploration of this cult figure’s complicated biography. Electric Lucifer will premiere at The Kitchen in New York Jan 9-13, 2018. We spoke to Jim to find out more about the project, the cult figure Bruce Haack, and Jim’s 20 year obsession with this enigmatic character.

We spoke to Jim Findlay before the premiere of his show.

Alex Teplitzky: How did you find out about Bruce Haack?

Jim Findlay: I found out about him just through combing record store bins for weird ephemera. This was quite a while ago. My brother brought his record into the room when we were working on a piece 15 or 20 years ago. It was a curiosity to me. The first record I heard was a contemporary rerelease of his collected children’s music. After I got hip to his children’s music, I got a hold of his Electric Lucifer record. It’s a whole different thing. When I listened to it I sort of had an immediate vision, “You could really do something with this and make a big visual spectacle out of it.” It felt very visual to me. It wasn’t anything fully developed, just a flash of an image, but over the years I would daydream about it. And when I got to a point in my career where I felt like there was support for something of this scale, it came boiling back up from my fantasy world.

About three years ago, I put the project on the front burner and really started working on unpacking what Haack had been up to. I approach all my work by asking questions instead of providing answers. I have to flounder in the dark and figure out what the essential questions are and pull those threads until they take me somewhere unexpected. Reading some of the materials around the album and music, Bruce talks about suffering and redemption. And that led me onto this track of the whole idea of a religious pageant, and even religious theatricality, going back to renaissance painting, the liturgy and form of church services and praise songs.

As I kept sort of peeling things back, at it’s base, all religions seem to be at heart really dealing sort of universally with this question of suffering. I grew up with religious parents and rejected that as a young adult, but I never really rejected the pageantry part of it. I only rejected the dogmatic part of it. I would credit church with being my inspiration for making theater in a way. It was the performative aspects of church when I was young and impressionable that gave me this feeling that what happens in a room between people is special. I’ve always pursued that feeling of specialness that I probably first felt in a church.

And at the same time, I started learning about Haack’s life—and without airing any details, I found that his life could have been more comfortable in a lot of ways. I can say that he wasn’t unacquainted with suffering. Listening to his music, the optimism that’s on the surface obscures a more hidden subterranean struggle that feels essential to why he would be inspired to create music with religious themes and characters.

Alex: That’s what I wanted to ask next, actually. Your pursuit of Electric Lucifer seems as much about the concept album as it is the subject who made it. There are these two sides to Bruce Haack: by day he made children’s music and by night he made this darker, more experimental work about Lucifer and suffering. In your piece are you exploring his biography?

Jim: I’m definitely exploring his biography. When I approach the Haack, I pull the thread out of the record: what is redemption and what is suffering? I got this record that I want to make into something, but I don’t immediately know what it is about the work. The material is rich in some way that will lead me somewhere. That’s where I have to start a project: feeling like there’s something here I don’t understand. The first thread I pulled out about suffering and redemption: I was asking myself why Bruce was interested in a character that he says needs redemption, in fact, he needs a new power in the universe so powerful that it can redeem even the worst of us, even Lucifer. I found that idea interesting because I’m not familiar with any other stories where the redemption of Lucifer is part of it.

Bruce Haack was inventing tools and pushing them as far as he could to create unexpected results, but if we tried to just recreate the results he came across 40 years ago, that wouldn’t be true to his vision in a way. The way to collaborate with Bruce Haack is to keep pushing and to try to create unexpected results.

There’s a little precedent. Bruce was writing Electric Lucifer around the same time that Jesus Christ Superstar appeared. These religious things were kind of in the air. But Jesus Christ Superstar looks at Judas as this sympathetic character. Judas’s choice is portrayed in a way that you have some feelings about it, that aren’t just like, “he’s an asshole.” We’re meant to identify with the choices Judas has to make. But I thought Bruce’s piece is over the top. If Judas can be a sympathetic character, how can we make Lucifer a legitimate, sympathetic character?

I say I’m collaborating with Bruce Haack. He just happens to not be able to participate in this stage in an active way. He’s done a lot of early work, and we’re collaborating with the materials he’s given us.

A rehearsal of Electric Lucifer. Photo by Paula Court.

I started working on this around the time that Mahmoud Salahi’s Guantanamo Diary came out. When I asked myself, “what is irredeemable?” I started thinking of him. What does it mean that we have these people that we think of beyond the justice system—people no longer part of society or subject to law? We put them in this gray area that’s completely subject to unencumbered state power. Who in that story is the Pharisee or Pontious Pilate? Who in that story is the kind of character that Jesus represents and associates with? If you look at that, it all unravels. The idea of forgiveness or redemption turns back on itself. It would be one thing to redeem a terrorist. But if our actions or complicity are also problematic, how do we redeem ourselves?

I personally felt guilty, too, thinking “I’m not doing enough to raise my voice against [the treatment of people like Mahmoud Salahi].” I’m paying taxes, so I’m paying the doctors to torture this guy. We’re all complicit in this. This was all well before the current political moment.

Around the same time I went to visit Ted Pandel, who was Bruce’s life long friend. Bruce lived in Ted’s basement starting in 1974 until he died there in 1988. Ted invited me to visit him in his house where he still lives. It’s not a shrine or anything, but there are a couple of filing cabinets that have all of Bruce’s papers. There’s a bookshelf with 250 reel-to-reel tapes that are Bruce’s work product. Bruce Haack was definitely an amazing progenitor of electronic music, but he was also an amazing tape artist. Tape is equally as important to his process as the electronic instruments he was inventing.

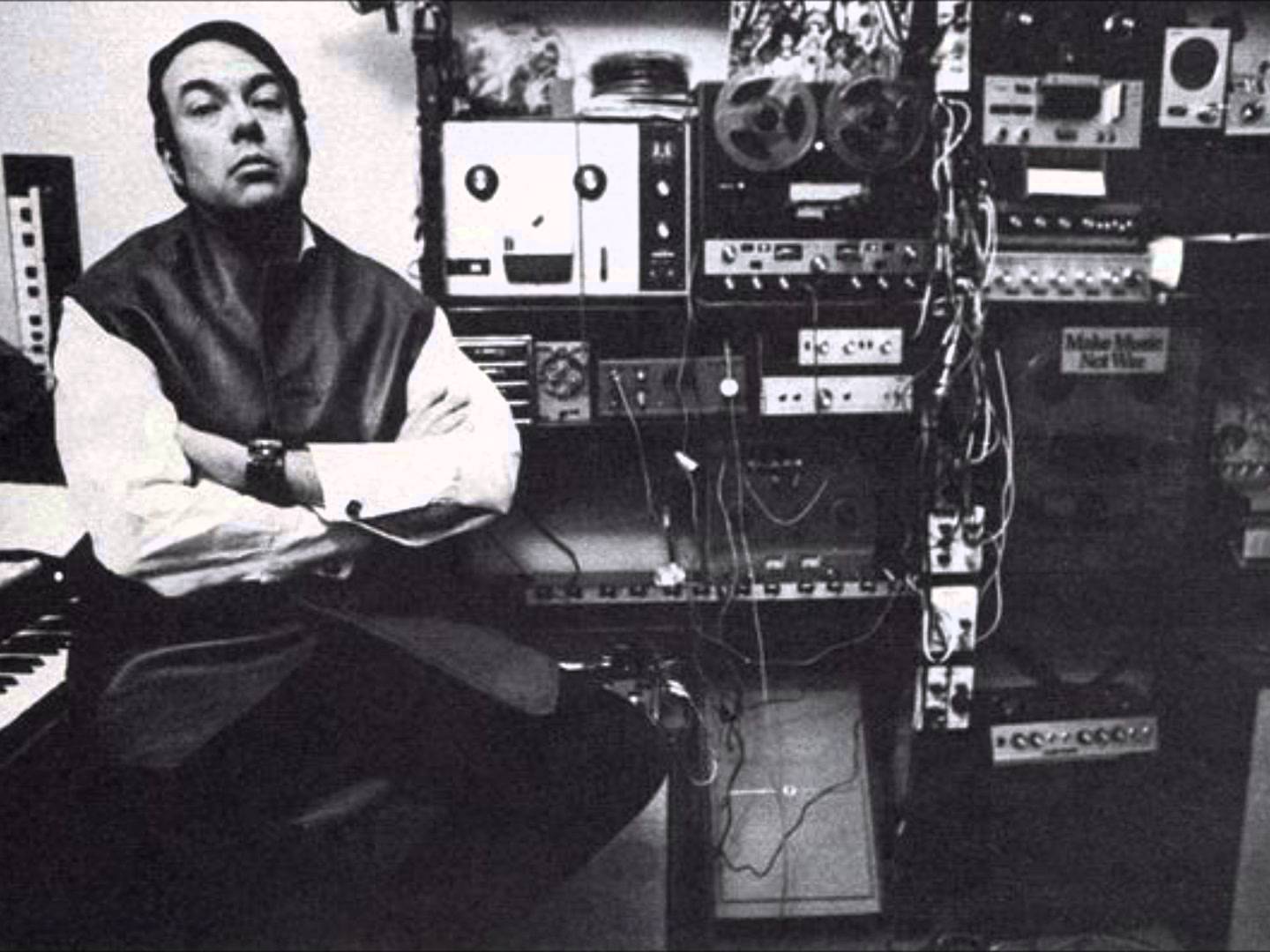

An image of Bruce Haack in his studio

Alex: I also wanted to ask about this emerging form of electronic music that he was a part of. To people listening to electronic music for the first time during Haack’s time, it might have felt scary, evil, or nonhuman. So, the idea of representing Lucifer through this music isn’t unimaginable. Is there some part of this project that explores the early history of electronic music?

Jim: More than electronic music as a genre, I related to Bruce’s circuit bending and hacking ethos. I’ve always made work by using tools that weren’t meant for the job. Early on in my work, well before video became a thing, I was using video in weird ways. I would take consumer electronic items in ways that they were never intended be used.

Alex: Exactly, there’s a sort of perversion to this form Bruce invented, and perversion is an element of Satanism.

Jim: There is a kind of dark magic to it. The story goes, when Bruce started building instruments in as early as the late 1950s, he would go to Canal Street and go into those crazy electronic surplus stores and buy boxes full of random electronic parts. He would just build his own circuits. When he appeared on Mr. Roger’s Neighborhood, the instrument he demonstrates is all of these oscillators that had been mounted to a kitchen dish strainer. Bruce was very high-brow and low-brow. He took this high technology, or technology that most people don’t understand, and combined that with a piece of common kitchen equipment. I related to that on a nerd-level. Here’s a guy who’s always like, “What happens if I put these two things together?”

Electronic music didn’t exist when he was working. He was inventing it. Bruce would plug two things into one another and make new sounds. I don’t really relate to a genre of music, so much as that tinkering.

His other major accomplishment was that Bruce repurposed the sound of military vocoders to create a singing voice. Bruce is basically the father of autotuning, electronic singing. His shit was weird early!

I had a private conversation with Ted, which helped me imagine myself in Bruce’s shoes. There is one story that Ted told me that I don’t mind sharing. It had this big effect on me and it’s still hovering over the show. He told me that when Ted went to work in the morning, he would see Bruce in the window of the basement where he was living. He said Bruce would keep this plastic lobster by the window. If Bruce saw Ted leaving for work, he would wave this plastic lobster at him. Ted told me that one morning he went to get into his car, and he thought it was strange that Bruce’s lights weren’t on. Ted assumed Bruce had been up late making music and he was still asleep. He remembered noticing that Bruce wasn’t there waving the lobster. When he came home the lights still weren’t on, and that’s when Ted found out Bruce had died of a heart attack the night before.

This story of this guy waving a lobster was this surreal image for me. That’s been this touchstone for me. Is Bruce waving goodbye or waving hello? Somehow for me this represents whatever suffering that Bruce was putting into his music. He had such a weird sense of humor. Now you would call it nerd-chic. He was goofy but also honestly excited about all this stuff.

He also liked dark imagery, not just in Electric Lucifer but in the albums Haackula and Bite. There are a couple of skulls in Ted’s basement. Ted told me Bruce liked having skulls around. There’s something dark and light about the guy. I’ve just been trying to pull threads to find my own way to my own story that makes some kind of sense of Bruce and suffering.

Alex: So we should be looking for lobster imagery when we see the show?

Jim: I can guarantee that there will be some sort of lobster imagery.

Alex: [laughs] I like that little Easter egg! So, moving from the subject of the story. When I saw the Kickstarter campaign I noticed how many people are collaborating with you on the project. Okwui Okpokwasili, among others. What’s it like to be this grand orchestrator of all this?

Jim: I have a history of doing big projects and then licking my wounds and doing small projects. Once I’ve gotten over my PTSD, then I get ambitious and make a big project. I’d say it’s a life long pattern in my art-making career. So, I’m not unfamiliar with the scope of this project, but I am unfamiliar with music as the central genre. I’m an amateur musician, but not by any means a very talented one. I knew at the beginning that the most important thing was to find a musical collaborator. I’ve been working on the project for three years on and off. It took a while, but I really found the right person: Phillip White, who is the musical adapter and composer of additional music of our piece. Philip is cut from the same cloth as Bruce, an alchemist of juxtaposition and also really also a pioneer of using autotune as an artistic tool in a way that’s not just to create ‘pop’ sounds. He is such a natural fit with this project. I’m lucky.

In one of his interviews, Bruce was talking about some new technology that would allow him to play his music live for the first time. As far as I know, he never performed his electronic music live. So, I always wanted my piece to be performed by a live band—and Philip’s own brand of mad genius is making that possible.

Photo by Paula Court

Alex: Do you think that because of how technology has developed, that it’s only now possible to realize Bruce’s vision of playing electronic music live?

Jim: Well, it’s probably been “possible” for a while. But Bruce did lament in an interview that the tools he needed to play his music live weren’t yet available. He was inventing tools and pushing them as far as he could to create unexpected results but if we tried to just recreate the results he came across 40 years ago, that wouldn’t be true to his vision in a way. The way to collaborate with Bruce Haack is to keep pushing and to try to create unexpected results.

Those were the directions I gave to Philip. I said, “Let’s push.” What would Bruce do if we had the tools that we have? I mean, he had nothing digital! It’s all goddamn analog oscillators and analog synthesizer circuits. There were no computers making music!

Alex: He wasn’t looking at screens.

Jim: There were no screens! It’s astounding what he did. So the music in our piece is totally updated. Phillip and I have taken the opportunity of taking these pieces that Bruce created and figuring out how to string them into a story that would be interesting for us.

So, there is a lot of collaboration because of all the things going on. We have to represent a war in heaven, a war between 7,400,000 angels, and God and the archangels. We have to represent a whole new species of creatures that Bruce imagined called “silverheads” which are sort of like quasi-devils that mated with humans to become cyborgians. There’s a lot of work to do.

Creative Capital is very good at saying, it’s ok to slow down in order to be strategic. And their main message is that you can apply it to any aspect of your art-making practice. You can be strategic about how you’re going to develop the art part, but you can also be strategic about how you’re going to develop the marketing part, or the fundraising part. All of those things benefit from strategic thinking: laying out a plan ahead of time, so you’re not being reactive.

Right now we have a cast of 7 and a band of 4. I could easily make it for 20 people or 40 or 60, because the themes are totally scalable as long as the central themes are there.

Alex: You’ve been working on this project for 15 to 20 years. I can’t even imagine what it’s going to be like for you to see it on stage finally.

Jim: Just hearing you say that… when the band kicks in and the performers are on stage, it’s going to be emotional for me. When the whole engine is humming. I’m really looking forward to it. I feel excited like a child just thinking about it! It’s going to make all the suffering feel worth it.

Alex: How has Creative Capital helped in the whole process?

Jim: Without Creative Capital this piece wouldn’t be happening. I say that in a number of ways and not just because they are one of the main funders of the piece. I was lucky enough to get invited to a professional development weekend many years ago because of a grant from MAP Fund. Even from that moment, Creative Capital was so supportive of me. They gave me that mental change of thinking of myself as a problem-solving unit, being able to compartmentalize problems.

Creative Capital gave me the freedom to say, I’m an artist and here’s what I want to do, and here’s why it needs support. Even being able to articulate that came from Creative Capital’s professional development. Then, getting the award and becoming part of the Awardee cohort. It made dealing with such a big project much more manageable.

And Creative Capital isn’t doing any producing work or heavy lifting. It’s just to know that there are resources to get things laid out the way you want, and being able to take the time to do them. I could have pushed this project forward quicker, but I really wanted to take the time. Creative Capital allowed me to take the time and say, I have this resource. It’s not enough to do the whole project, but it’s a big resource. The only thing I could do wrong was to push it forward too fast so that I don’t have the support to do it in the way that I want to do it. Creative Capital is very good at saying, it’s ok to slow down in order to be strategic. And their main message is that you can apply it to any aspect of your art-making practice. You can be strategic about how you’re going to develop the art part, but you can also be strategic about how you’re going to develop the marketing part, or the fundraising part. All of those things benefit from strategic thinking: laying out a plan ahead of time, so you’re not being reactive.

The truth is this project has faced a lot of challenges that were unexpected. We were booked in a venue that canceled on us. We’ve had resources pulled from us that we had every reason to expect were secured. I have to say my producer and I have marveled about all the weird things that have gone wrong with this project. But for everything that has gone wrong, something else has gone right. Every time we’ve had a major challenge that felt existential, somehow we failed into success again. I think that’s because we’ve been strategic and we’ve got things laid out. So any one set back only affects one part of the plan and not the whole plan. That has been the biggest help from Creative Capital.

Buy tickets to see the premiere of Electric Lucifer by Jim Findlay, taking place in New York, Jan 9-13, 2018