An Opera About Sarah Winchester Lends a New Voice to Gun Violence

The national conversation about gun violence has reached a standstill. Concerned about this impasse, composer Lei Liang, writer Matt Donovan, and visual artist Ligia Bouton teamed up to make an opera that cast the story of Sarah Winchester as a fresh perspective. Legend has it that Sarah Winchester—heiress to the Winchester rifle fortune—created a labyrinthine mansion to escape the spirits of those killed by the same weapons whose manufacture gave her a life of indescribable wealth. The opera uses Winchester’s biography to explore America’s complex relationship with guns and violence. Their Creative Capital Project, Inheritance, premiered October 24-27, 2018 at ArtPower at UC San Diego.

We spoke to Ligia, Matt, and Lei, as well as Susan Narucki (a 2006 Creative Capital Awardee), who sings the lead character and produced the opera, and Cara Consilvio, director.

Alex Teplitzky—Can one of you describe the project for me?

Matt Donovan—Maybe I can talk a little about the history of the project to get into it. When I was asked to participate in the project, I didn’t have any experience writing for the stage or for opera. It was definitely a creative challenge that I was eager to pursue, and I also was thrilled an honored to work with the entire creative team. The idea came up to develop a chamber opera before the content, focus, and subject was determined. All of us wanted to develop a project that would have resonance and meaning beyond the world of opera, and we wanted to address a topic that meant something to us. All of us were deeply concerned about gun violence in this country. We’re deeply concerned about the standstill that our country seems to be at in terms of firearms, and also the increasingly polarized divide that seems to be more and more entrenched every year, or every day for that matter. We wanted to develop a work that would foster engagement with this really complicated subject.

All of us also wanted to pursue it in a way that wouldn’t be didactic—that wouldn’t presume, that wasn’t designed from the outset to instruct, but would be an invitation to engage, and move out of those polarized boundaries. That’s when the idea for the Winchester subject locked in for all of us. The idea was that we would develop the opera that would focus on Sarah Winchester and her biography.

According to legend, Sarah Winchester—as the heiress of the Winchester rifle fortune—was deeply concerned about her own complicity in the deaths of so many people through those weapons. She went to a psychic in Boston (this is the legend, slightly apocryphal, but the legend nonetheless) who told her to move West and build a house that needed to be kept in constant construction, or the spirits of the deceased would have their revenge upon her.

So, she did exactly that, according to legend—she built this house that kept workers around the clock, there was constant hammering, to ensure that the building was under constant construction. There was not so much a plan or design to it. It was just this labyrinth that kept building upon itself.

For all of us, we really were interested in how Sarah Winchester was someone who seemed to be a very compelling, sympathetic character, someone who was emblematic of a stance that so many Americans feel, which was a concern about guns. For Sarah Winchester, and a lot of us, there’s ultimately a complicity in the violence that has ensued. Yet, the end result of all of that guilt and complicity and concern is an impossible labyrinth built upon a fantastical premise from which there is no real resolution or escape. The richness of that metaphor really appealed to all of us.

That’s when we started chasing it down full throttle to see the possibilities for exploring the metaphor of that premise, and the vicissitudes of her character might be for the team and the project.

Lei—For me, the project was an organic extension of a few threads of friendship. Susan and I collaborated on an opera called Cuatro Corridos, that dealt with social injustice. It’s about sex-trafficking across the US/Mexican border. Working on it was a very inspiring experience for me, personally. I thought that Susan and I shared this passion for doing something with our creative work that intersects with issues that matter in our society, or dialogues that needed to take place. So, we just loved that experience, and wanted to continue working together.

Meanwhile, I lived at the American Academy in Rome for eleven months, where I met Matt and Ligia. That was one of the best times I have had since college. We had coffee every morning together, and had many inspiring conversations about all kinds of things. I loved Matt’s poetry, prose, and the readings he gave at the Academy. Ligia’s work was astounding, and I just fell in love with it. We wanted to work together before we had any idea what to do. When Matt proposed this story, Susan and I thought, this was it. This was the story we knew we wanted to work on.

When we think about something like guns, as an individual artist it is such a huge and overwhelming topic. It is so complex, and it is affecting our country in so many different ways that it’s hard to imagine how you could even begin to have engage in some kind of meaningful way with that conversation. There’s something really unique about opera itself that allows for the power of multiple professionals to come together to collaborate in a way to make something that is much bigger than any of them could have done alone.

Alex—Opera really seems to be one of the forms that artists are using to talk about social issues in the country. How do you see the form of opera lending itself to this conversation particularly?

Lei—I’ve always been fascinated with early music, especially the earliest operas. Monteverdi is one of my heroes in music history. I’ve also been involved in experimental music for a while, and I see a very interesting parallel between these two worlds. Early operas were very experimental in nature. I found this particular form, contemporary opera, a versatile expression to confront issues that are most difficult. That’s why I embraced this form, but Susan and Cara know a lot more.

Susan—Opera has been in existence for 500 years. It’s been in a constant state of transformation. I think that there’s a generation of artists that are transforming the genre, and want opera to engage with the broader community. Opera has been labeled as an elitist art forum, but in fact has been part of national identity, especially in some countries in Europe. Our project is another way in which artists are starting to reclaim the power of this genre.

Alex—In a perfect world, what do you all see this opera doing that’s outside of the performance itself? An opera that inverts social order isn’t just a performance, it does more than that. So, what would Inheritance do?

Cara—My hope is to use empathy to move people to a place where they can think in a different way. When people feel strongly about a particular issue, like guns, it’s hard for them to get out of their patterned thinking. If you use a human story, like this one, sometimes empathy is something that can move people out of their patterns, to make them think, “Is this where we want to be?” It’s not looking for an outcome one way or the other with guns, but it is hoping to get people thinking about the current state, and where we maybe could be in twenty years.

Ligia—One of the things that I’ve been thinking about throughout this conversation is how, historically, opera has brought together artists from different disciplines to collaborate in a holistic way. I think about how the innovation of stagecraft really came through early opera production, and how artists and designers, writers and composers, and then, of course performers, all came together to create this collaborative project.

When we think about something like guns, as an individual artist it is such a huge and overwhelming topic. It is so complex, and it is affecting our country in so many different ways that it’s hard to imagine how you could even begin to have engage in some kind of meaningful way with that conversation. There’s something really unique about opera itself that allows for the power of multiple professionals to come together to collaborate in a way to make something that is much bigger than any of them could have done alone. This particular issue with guns is such an issue where it feels like we all needed to come together for this. There’s something in the project itself about that.

Matt—I love both of those responses. One of the things I love about what Cara says is that I think that notion of empathy is its key to any possibility of change on this very topic, and I mean empathy on both sides of the issue. It’s also a realization we all came to through the gradual workshopping and distillation of the project’s text. It’s not something that we set out to embed in and find in Sarah Winchester’s biography, but the more that the project evolved, the more we discussed the themes we were finding, the more that that exact idea of empathy came to the forefront.

I think music, narrative, poetry, and song has great power to awaken precisely that in the audience. It’s an opportunity for the audience to think about this issue in a way they haven’t before because currently nothing that we are doing seems wholly efficacious either. This is just another way to foster dialogue, and harness that concern that we’re imaging a lot of our audience members might share.

Alex—I actually heard a lecture by someone that is working on a biography of Sarah Winchester, and she argued against the mythical stories of her—she argued that actually Sarah didn’t have the kind of empathy that you are asking your audience to have. She actually was completely OK with having inherited a fortune from guns. How do you deal with the complexity of the Winchester story?

Matt—There are a lot of different versions of Sarah Winchester out there. There’s the Sarah Winchester that the estate is harnessing toward the kind of tourist attraction that her house has become. There are revisionist biographies. There is Helen Mirren’s portrayal of Sarah Winchester in a recent b-grade horror movie. So, I would say we don’t fully know who the real Sarah Winchester was, and there is a plurality of selves that we try to bring forward in the version of her that we’re presenting.

Additionally, I think the complications of understanding the past and the different versions of the past actually dovetails beautifully with our interrogation of the Second Amendment and firearms in this country. There are so many different versions of our country’s relationship to firearms, and the fact that the past is murky—the fact that we all see it differently—is something that we really want to bring forward in this production. There are romanticized versions of the West, the confusion about who this person was—all of that confusion is also tied up with our engagement in Second Amendment rights in this country. So, it actually assists us in some ways.

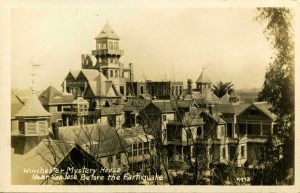

The Winchester “Mystery” House near San Jose

Cara—We talked a lot about who Sarah Winchester is in rehearsal, and there are two things that stuck out to me. After she died when they opened her safe. They thought it would be full of jewels, but there were only two things in it: a lock of her hair from her daughter who she lost when she was only a month old, and a lock of hair from her husband.

The other story that touched me was about her driver, who had been with her in Connecticut and had taken her to California. When he died, Sarah was so shocked that she went into mourning for a long time. She continued to take care of his family, she gave his widow a house, and a source of income.

Sarah Winchester wasn’t a public person. Usually you can judge people based on who they are in public and private. Because she was not out in the world it’s hard to judge her, but one of the things we discovered was that most of her actions were driven by this deep sense of grief. The whole reason she moved to California was to start a new life because of the loss of her daughter and husband.

Alex—Are those some of the stories referenced in the opera?

Cara—No, those particular stories do not come up, they’re just background to the story. But there’s this sense of grief throughout. Because it is about a historical figure that ties to contemporary times—it takes place in a school and references a school shooting—for us, this idea of grief is timeless.

Susan and I have talked about this a lot: Sarah Winchester inherited all this wealth, but we both think that if she was given the choice to have one more day with her daughter, she would trade it all away. I think for parents of children who are killed in school shootings, they would do anything. That is an important tie for us between the present and the past: the inconsolable grief of a parent losing a child

It was through the force of collaboration that I could see the ways in which the work was being improved—exponentially through the forces of everyone weighing in.

Alex—How do you all collaborate with each other? You each represent so many disciplines—how does it all come together?

Susan—Some of us are playing multiple roles. In this project, my role is to create and sing the lead character, Sarah Winchester, but also to serve as producer of the opera. That means assembling the funding, leading the logistics of the team. Although we’re fortunate because we have great support from our institution at UC San Diego—and there’s a wonderful team here and in our production staff—every single day many questions have to be answered that are unanticipated.

Lei—In addition to our school where Susan and I both teach, the generous support from Creative Capital and the National Endowment for the Arts made it all possible. Susan is an amazing leader for our team because none of us have this kind of experience. The entire project has been guided by Susan’s wise and steady hand for the last few years.

I found this collaboration to be an eye-opening experience. I always collaborate, but I’ve never collaborated in such a complex situation before. Matt and I both approached this project with very little experience in opera writing, I’ve only done one scene in an opera before. So, it’s a really beautiful process: we were both challenging ourselves to learn how to adapt to this new form.

I was inspired when I received the initial drafts from Matt to see how musical he was. He’s very natural with a musical imagination, telling the story with different voices, the pacing, and the rhythm, the tone. He gave me very interesting materials to work with. On my side, I feel like I’ve always written music for specific people. This opera has taken that to a higher level because I had very specific people and their specialty in their instruments in mind.

Artists Ligia Bouton, Lei Liang, and Matt Donovan collaborating on their opera

Of course, I wrote this for Susan. I fell in love with Susan’s voice the first time I heard it ten years ago. There’s so much for me to explore in her voice. Susan probably doesn’t know this, but I observe her when I listen to her talk. There’s so much beauty in her voice that I can explore in this opera. Yes, there is singing, there are arias, but there’s also just plain speaking because I feel that Susan’s voice has very different expressive ranges. Those are the things that I am engaging with.

That’s just one example of how I wrote, in my way, for the percussionist, the clarinetist, the harpsichordist, for the guitarist, the double bass—these people are capable of doing very unusual things. And opera can be that experimental test ground to bring forth the kind of humanity we’re trying to put in the work.

This process has been really fun. Also, the open endedness of it is very new to me. Susan communicated to me at one point that the team isn’t looking for a finished score. That is a new concept for me as a practitioner in my field. When I work with an orchestra, I try to create as perfect a score as I can. But that openness, and ability to work with the team is important. Knowing that Ligia is going to create a beautiful stage will now inform how the performers move their bodies, and I will take that into account somehow. It’s a luxury I haven’t had before. Opera is a more open collaboration, and I’m learning a great deal from that. It’s a great privilege to have this experience.

Ligia—Matt, Lei, and I came to this, as Lei mentioned, with no experience in the field of opera, and I have never worked in the field of theater. Part of the luxury in working with a team of this caliber is to feel over the last couple of years I have learned so much with the people I am working with. I’m constantly in a position of looking for feedback, and considering it. In my own work, I work so much with narrative. The joy of working with the narrative Matt’s came up with, and Lei adding his music as a layer to it—thinking about my design with the layers of music was all a completely new experience. Every conversation I have with Susan and Cara is just eye-opening in teaching me all the ways in which things I’m thinking about need to be shifted in terms of specifics of the theater. To be a teacher, learning is a privilege. I’m so thankful for this experience.

Alex—I don’t know that much about opera, but the more I hear you all talk about it, it feels like this impossible medium!

Susan—People should come and watch rehearsals! It’s amazing to see how we take all the elements: the music, the idea of what the set will be, the director’s vision for the characters, and the singers’ synthesis of the elements in space. It’s like watching a building being built!

Matt—I wish I could be there!

To answer your question in a really direct way, in the initial stages we were geographically all separate. So, there were a lot of Skype sessions where we were drilling down into the texts, and addressing particular scenes. Even though every collaboration has its inherent complications, it was so gratifying for me to see the ways in which those individual sessions were really directly addressing issues with the text that could be strengthened. It was through the force of collaboration that I could see the ways in which the work was being improved—exponentially through the forces of everyone weighing in.

It was so fantastic to know my own thoughts in isolation weren’t anywhere close to what we could achieve together as a group. At the heart of the piece’s development, too, we all met at the BANFF Centre for a residency where we could have a more immersive, contiguous experience. That came out directly out of the Creative Capital Retreat. That week was utterly invaluable to the piece’s development where we could think about it holistically, and think about it together. Collaboration has its inherent difficulties, but I felt, as a team, we were so receptive to each other’s ideas.

Alex—Speaking of Creative Capital, how did you use the support to help strengthen your work together?

Matt—I found the Creative Capital Retreat—where we had all of these projects being presented that are so dynamic and compelling—so inspiring for this project. To find a way to make work that could reach an audience, and have a meaningful resonance in this era, and that would reach an audience in a more direct way. I think that’s something that Creative Capital is just fantastic in doing: they want you to find ways to be self-reflective and thoughtful about the audience that you’re trying to reach, and what you’re trying to do with your work. They’re also incredibly concrete in thinking about logistical necessities as you move forward. It’s been both inspirational, and so deeply educational about what’s needed for this project, and the pieces as a whole, creatively.

Ligia—I second that. The Retreat was an incredible experience. Matt and I left there, and we drove seven hours to pick up our kids, and we just talked the whole way. It was like this flood of ideas and thoughts that had come out of that four or five days that we were there. It was an incredible experience: the people we met, the stories we heard, the projects we were introduced to, and the ways we were asked to think about our own work, and how this project might expand. I really professionally never have been through an experience quite like that.

Read more about Inheritance, and the artists’ work together.