Alison O’Daniel’s Sundance Film Festival Premiere: The Tuba Thieves

Alison O’Daniel’s Creative Capital film, The Tuba Thieves, premieres this Sunday, January 22, at Sundance Film Festival. Awarded the Creative Capital Grant in 2019, the Deaf director presents the impact of a spate of tuba robberies from an unexpected angle in her first feature film. The film unfolds like a game of telephone, where sound’s feeble transmissibility is proven as the story bends and weaves to human interpretation and miscommunication. The result is a stunning contribution to cinematic language. O’Daniel has developed a syntax of Deafness that offers a complex, overlaid, surprising new texture to the dimensional experience of Deafness and reorients the audience auditorily in unfamiliar and exhilarating ways.

Read on for a behind-the-scenes look at the making of this project.

In the fall of 2011, like many Angelenos, I heard stories on the radio about tubas that were stolen from multiple high schools in Los Angeles. When the stories were reported, the focus was on the thieves and why they would do this. I was curious about the students’ listening experiences in the band, and how the sound changed. I live on the Deaf spectrum and I’m endlessly curious about sound and its impact. In 2011, I started keeping a notebook about the details. I reached out to the band directors and went and visited any classes that would allow me to. I went to four different schools. Centennial High School in Compton was the school that welcomed me in with wide open arms. The students were phenomenally talented and good natured with me. Manuel Castaneda, the band director, and a trumpet player, is a true visionary and artist in the way he teaches. He is open minded and supportive of ideas and experiences for his students and he never made me feel like a weirdo artist. He’ll be going to Sundance with us!

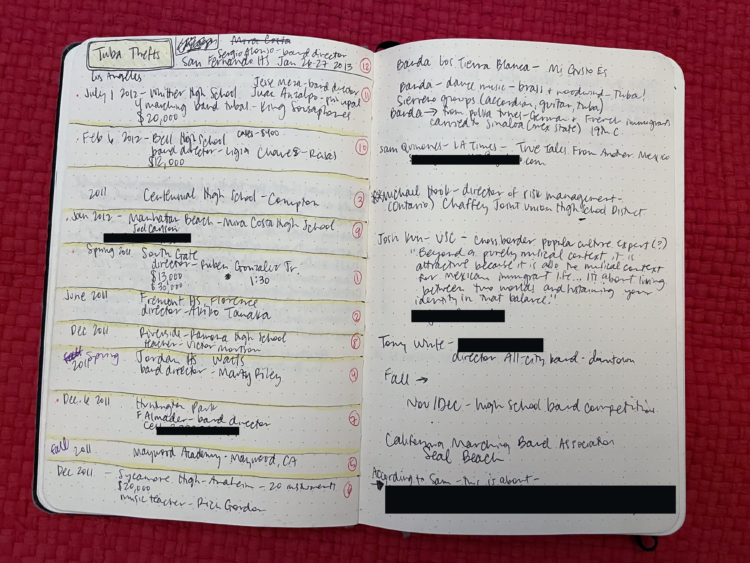

An 11 year old notebook that has weathered and carried the research for this project.

This was one of the early pages where I started and continued cataloging the thefts as they were happening. It also shows notes from my very first conversation with Sam Quinones, an L.A. Times reporter at the time whose research was respectful and comprehensive. When I was visiting schools, I was always one step behind Sam. He is now one of the main characters in the final film.

Alison O’Daniel, bottom right, in 2017. Photo by Gina Clyne.

Here I am posing with Manuel Castaneda looking very sharp, and his marching band from Centennial High School. Geovanny Marroquin, center in white, was the drum major. I have filmed with this band or members of the band four times for the film and also collaborated with them on a performance at Art Los Angeles Contemporary art fair. For this performance, I asked the students to co-author a performance with me based on the constraints of the art fair. This included the physical layout of the space, and the director’s and gallerists’ concerns about noise during the opening. I went to Centennial multiple times to rehearse with the band, and we ended up creating choreography and a medley that combined a Pauline Oliveros (my idea) score with band songs they perform at football games and an Eminem song (their idea). The Tuba Thieves is a project with tentacles. It has included performances, installations, sculpture, short films and a feature. I don’t consider the feature film the top of a hierarchy. But it is the most demanding and the most expensive. (Thank you Creative Capital for funding!)

After visiting the schools, I decided to make a film called The Tuba Thieves that would not focus on the thieves. I also decided to make the film backwards starting with music. I didn’t know what the film would be about exactly, but I knew it would be built through listening and my idea at the time (and now still) was to untether listening from the ears. I wanted the bands to be involved. I was open to everything else.

With $6000, I filmed a scene of plants singing (to match Christine Sun Kim’s voice) in the cargo of a 26 ft. Penske truck. Meena Singh and I set up a shot together here on the Arri Alexa camera with incredible macro lenses. I knew that if I was going to make a film over a long period of time, the quality of the image would need to hold up, so I committed to the fanciest of cameras and effectively forced my film into the gearhead zone.

In 2013, I filmed the very first scene from The Tuba Thieves. I had just finished a seven month residency at the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, MA. At FAWC, I wrote the screenplay for a feature film called The Tuba Thieves that all derived from listening to musical compositions I commissioned from the artists Christine Sun Kim, Steve Roden, and composer Ethan Frederick Greene. I came back to Los Angeles and was invited to be in my first group show in LA at LA Louver gallery and I decided to make a short film for it. I won a small grant from Arts Matters and looked through the script to see what scene could stand alone from the feature as a short film. I asked Cinematographer Meena Singh, who had been a gaffer on my previous film, to work with me on a feature film that might take many years to complete. I had no idea how filmmakers raised entire budgets for features, so I figured I would make it piecemeal. I just didn’t want it to take longer than 10 years. (It took 11.)

I was teaching as an adjunct at UCSD and at Otis and I had incredible students at both schools that year! A handful of them helped that day and some continued working on the film in various roles over the years. Here we all are ‘on set’. Photo by Rachel Main.

With this film, I want to relish the art of cinema, celebrate what cinema can do and be, expand audience expectations around how storytelling is done and experienced.

Also, so many stories of people with disabilities are hyper focused on the disability as trauma, and/or the stories get filtered down into basics that feel inauthentic and oversimplified. I really hope to widen ideas around Deafness, and offer our vantage point as a valid and important contribution in the conversation about sound, music and the aural world. We are so diverse and people tend to think in binaries of totally Deaf or totally hearing. I have never seen a film made by someone who is Deaf that is widely seen outside of the Deaf community. Rather, the films about Deafness are often made by hearing people.

The Tuba Thieves crew setting up a big crane to get a sweeping shot of the forest reflection across all of those diagonal windows on the facade of the Maverick.

The Tuba Thieves honors an intricacy around the perception of sound, whether the perceiver is human, animal, or plant. I love the idea of Deaf Gain—this is a term that flips the phrase ‘hearing loss’ on its head (or ass). The idea is that Deaf people do not have hearing loss, but rather have a rich surplus of culture and perspective to offer, especially about sound.

Installation view of Hearing 4’33”. This was a two-channel installation in my first exhibition showing multiple scenes of The Tuba Thieves. All Component Parts (Listeners) installation view. Solo exhibition at Centre d’Art Contemporain Passerelle, Brest France.

When I commissioned the scores for the film, the musicians had no image to respond to, so I gave them random prompts. I had a photo of the Maverick concert hall and gave the image to painter/musician Steve Roden to respond to. We were both shocked to realize that I didn’t know that this was where John Cage had premiered 4’33”. Steve told me I must do something with 4’33”! At first, I felt dismissive. I love John Cage, but there are too many oversimplified comparisons of 4’33” to Deafness that I resist. However, I happened to be in Hudson in the winter of 2012, and I went and visited the space. It’s a summer concert hall, but I was able to visit one quiet evening when it was covered in snow. The wind was loud, and I realized that 4’33” was not at all about silence, because the first performance must have been inundated by the sounds of nature. I was shocked by the pervasive mythology of silence around 4’33”, which is the same misunderstanding that deafness is an experience of silence. That opened a door for me to explore 4’33” and I wrote a scene that focuses on an irritated audience member who gets up and leaves the concert behind to walk in the forest.

|

|

From September 2016–January 2017, The Hammer Museum invited artists to perform on a stage in the courtyard in their exhibition, In Real Life. I built a kitchen set and filmed a segment from The Tuba Thieves in view of anyone who wanted to come and watch.

Whenever you film, you’re constantly navigating cascading problems. During this shoot, we had a tight window to film at the Hammer and there was a huge, rare LA storm. At one point, we had to unplug everything and wait out the rain. Several days after, I felt so horrified that I had missed an opportunity to capture what could have been one of the most beautiful shots of the film. My advice: let it rain in the kitchen.

< |

|

Left: On a street corner in Lincoln Heights in Los Angeles, filming with cinematographer Judy Phu and crew in 2017. Right: A tuba in its case at Bell High School. The tuba is duct taped together.

Having the funds stored and available when I needed them was not only practically helpful, but also reassuring that I could take whatever amount of time the project required.

I received the grant in 2019, and utilized the funds and other forms of support over a period of five years. The Creative Capital staff and resources have been available to consult and advise when I needed particular resources. I found my lawyer through Creative Capital, I’ve worked with a financial coach, had a meeting set up with another Creative Capital artist to learn about how they bought a co-op, and taken advantage of other strategic resources. Creative Capital helped me slowly become better at supporting myself and my practice in a sustainable way, by not trying to do everything on my own.

I love the process of making a long form project. The Tuba Thieves has been elastic and flexible, an epic deep dive into making and listening, and I feel emotional looking back on the whole thing. There have been many moments when I didn’t really know how I would complete it, but I knew that I would. On a personal level, this project has validated my sense of capability as an artist, and also has been a marker of my own shifting understanding of my identity within Disability and Deaf culture.

I hope audiences enjoy the experiential and physical element of the narrative of this film. I have always had a goal to expose the audience to a huge range of audio in multiple forms, and I hope the audience leaves feeling internally quiet.

I am so excited to be with the cast in Park City and celebrate all the beautiful and generous work everyone contributed to it.

The Tuba Thieves premieres at Sundance Film Festival in Park City, Utah, on January 22nd at 12pm MT. It will also be streaming online from January 24th at 8am MT, through January 29, 11:55pm MT.