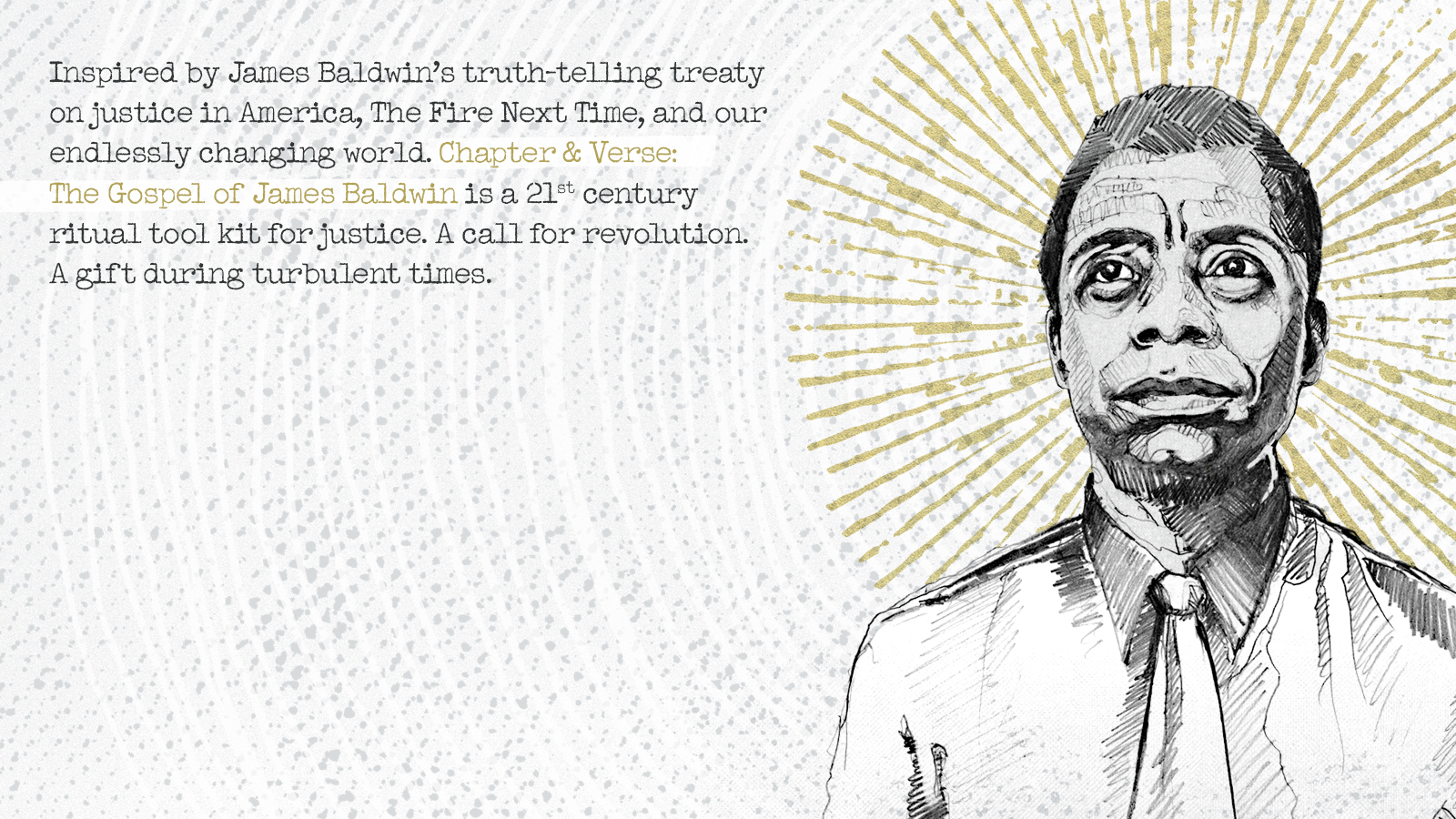

Meshell Ndegeocello and Collaborators Uplift James Baldwin as a Ritual Toolkit for Justice in Troubling Times

Images from Chapter & Verse: The Gospel of James Baldwin by Meshell Ndegeocello. Graphics by Rebecca Meek, illustrations by Mo Geiger, 2020.

In the early sixties, James Baldwin wrote a letter to his then fifteen year old nephew about the challenges he would face as a Black man living in the US. “Take no one’s word for anything,” he wrote, “but trust your experience. Know whence you came.” Over the past decade, Meshell Ndegeocello has been paying tribute to the writing of Baldwin through a church-inspired musical performance. When the pandemic began, Ndegeocello worked with her long-time collaborator Charlotte Brathwaite to adapt the piece to the restrictions of the time, turning her Creative Capital Project, Chapter & Verse: The Gospel of James Baldwin, into an accessible series of songs, thoughts, and meditations offered online and through a phone number anyone can dial for free. Institutions, realizing the importance of celebrating the words of Baldwin together despite limitations of 2020’s shutdown, have stepped in to lift up the project to their own audiences, starting with Fisher Center at Bard College. The work is digitally accessible through the end of December, 2020.

When Baldwin wrote that letter to his nephew some fifty years ago, the civil rights era was in full swing. It is poignant that this missive has become as one of the defining essays of the movement—not an invective speech, but rather an intimate, personal message aimed at the wellbeing of only one person. But the letter was shared with a wider readership, originally appearing in The Progressive in 1962, since becoming a cornerstone essay in the fight for racial justice.

Ndegeocello spoke to Creative Capital as her project circulated the world. Asked about the first time she read Baldwin, Ndegeocello answered that the better question was “when did Baldwin change my life?” She began reading, and rereading, The Fire Next Time in 2015. “It answered so many questions I had concerning my parents, my upbringing, and the state of the country which I call home.” Baldwin wrote to his nephew that by understanding his parents and grandparents, and the struggles they lived through, “there is really no limit to where you can go.” In an introduction to one of the videos on the Chapter & Verse website, Ndegeocello reflects on her parents, “the world they raised me in was troubled, harsh, filled with anguish, judgment, physical and sexual abuse, along with disturbing ideas about race.”

“Wouldn’t it be amazing if you could just pick up your cell phone—and instead of scrolling through Instagram or buying things, actually call a number that would somehow, even for just for 30 seconds, give you some sort of succor, or a moment to know what you feel is alright?”

Inspired by the way Baldwin used the written word to commune with others and give them strength, Ndegeocello has used her craft of music and performance as a vehicle to connect with and share the message of Baldwin’s words. “I try with all my heart to create work that allows others the freedom to think and create for themselves.” Once people experience Baldwin’s writing through her art, what they do with it is up to them. “There is so much wisdom in it that is so timeless and general but the connection to his work is personal. I just want to offer the opportunity to connect to it.”

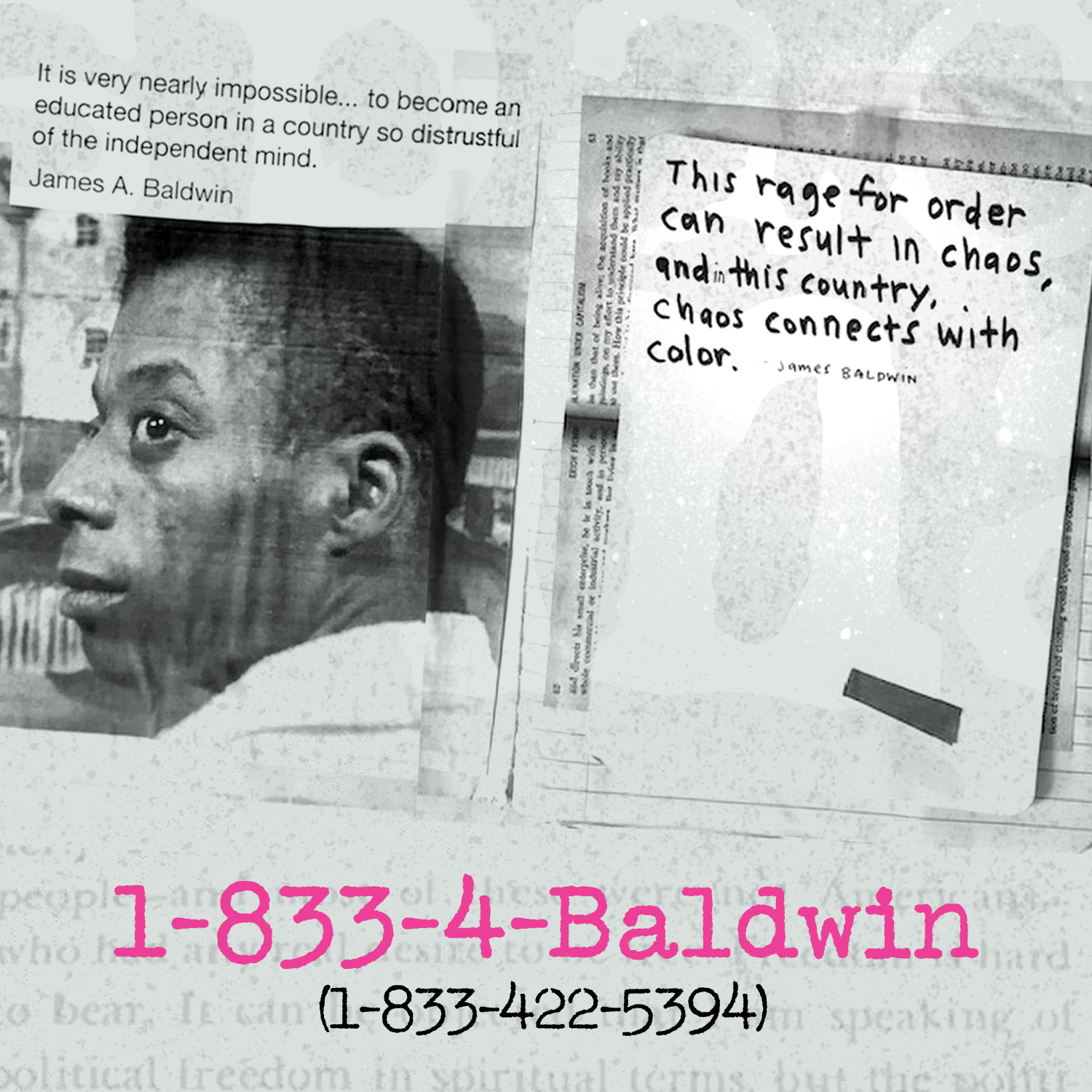

Ndegeocello organized an early first performance inspired by Baldwin, Can I Get a Witness?, just after the election in 2016 at Harlem Stage. In 2020, as the pandemic added to the challenges already faced by Black communities across the US, Ndegeocello started talking to artistic director (and another Creative Capital Awardee) Brathwaite to change the nature of the work. “Like most projects, we start with a conversation,” Ndegeocello says, “and the one issue we both agreed upon was that the experience of theater can feel stagnant.” Inspired by the Black Lives Matter movement that was gaining renewed visibility, they decided to create a phone line that anyone could dial to hear spoken word, music, and audio inspired by Baldwin.

“It was a conceptually brilliant idea,” Ndegeocello said. “Wouldn’t it be amazing if you could just pick up your cell phone—and instead of scrolling through Instagram or buying things, actually call a number that would somehow, even for just for 30 seconds, give you some sort of succor, or a moment to know what you feel is alright?” Ndegeocello worked together with artists Chris Bruce, Jebin Bruni, Justin Hicks, Kenita Miller, Abraham Rounds, Julius Rodriguez, and Jake Sherman to create an audible collage. The piece is also accessible through a website, a free downloadable Broadsheet, and videos.

Images from Chapter & Verse: The Gospel of James Baldwin by Meshell Ndegeocello. Graphics by Rebecca Meek, illustrations by Mo Geiger, 2020.

Recognizing the need to uplift and celebrate this reflection, the Fisher Center has spearheaded an initiative with a group of other institutions around the world, including MCA Chicago, CAP UCLA, and the Festival de Marseille in France. The audible collage has been translated into many different languages, and is intended to be, as Brathwaite wrote, “a call to action, a call to do something, a call to sing with a purpose and intention.”

Finishing his letter to his nephew, Baldwin implored him to rise above the negative expectations that he was born into, from the world outside of his family. He encouraged him to join together with others, even white people, writing that, “we, with love, shall force our brothers to see themselves as they are, to cease fleeing from reality and begin to change it. For this is your home, my friend, do not be driven from it; great men have done great things here, and will again, and we can make America what America must become.”