George Legrady’s 1973 Photographs of the Cree People Are Now Online

In 1973, 23-year old George Legrady (2002 Awardee) was invited by the Cree indigenous communities to photograph their way of life. The Cree people were about to enter negotiations to dispute a dam project that would flood land they had lived on for millennia. Recently, George received funding to digitally archive these photographs. Looking at them, I found a striking similarity between that moment in 1973 and the one we are living in now, as 280 First Nations tribes have convened to protest the construction of an oil pipeline in North Dakota. Wanting to learn more, I asked George to select a few images and share his experience.

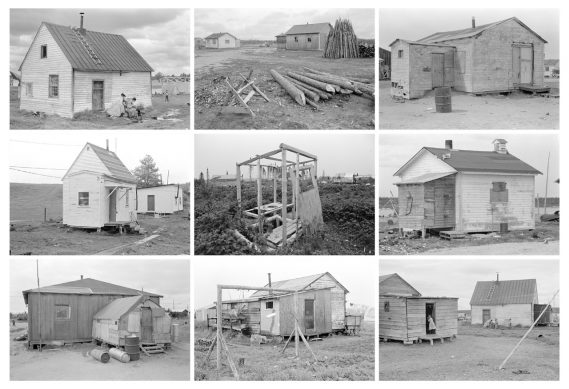

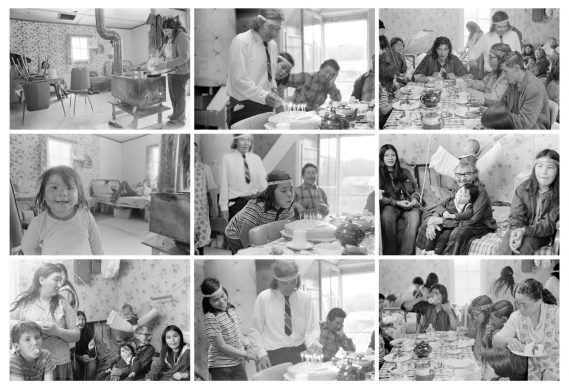

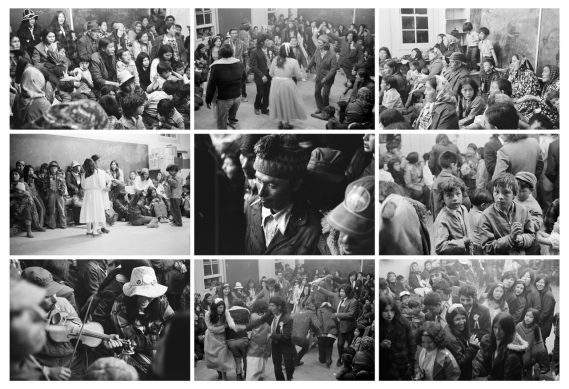

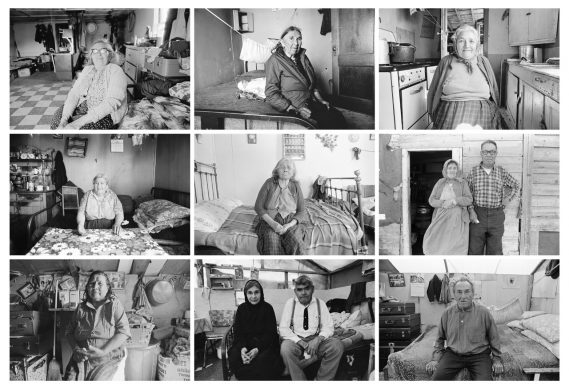

In 2012, I received a National Science Foundation Arctic Social Science grant to digitize the photographs and revisit the Cree to present the images back to the communities. Of the existing photos, I have digitized and archived about 700 to be used by the Cree and ethnographers. Below is a selection of 3 x 3 clusters of images from 1973 with anecdotal comments.

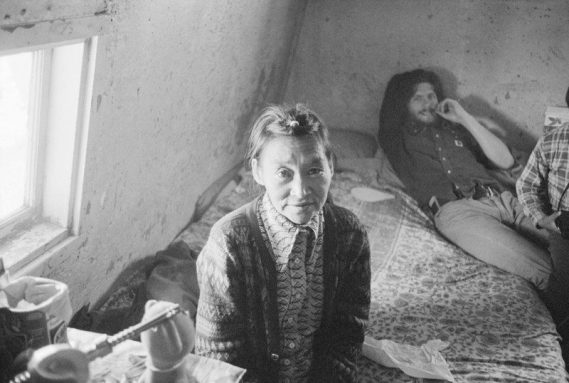

An Inuit woman, Maggie Ekoomiak, living in a Cree community in James Bay with artist George Legrady in the background

The James Bay Cree were in the news when the government announced in 1972 that they were planning to flood some of the Crees’ hunting grounds in northern Quebec, Canada, to create a gigantic hydroelectric dam. Known as the “James Bay Hydroelectric Project,” the dam was to flood land the size of England.

About 5,000 Cree had been hunting on traditional lands in northern Quebec since prehistoric times. The land equals about the size of Texas or Germany. The Cree had never signed treaties passing the land over to Canada. They began negotiations in 1973 and continue to do so to this day, but they have successfully managed to acquire control of much infrastructure in their communities, receiving royalties, and I believe, they now have “nation with a nation” status. The North has yet to settle much of northern Canada, but this may be in the process of changing as climate change opens up the area for mining, shipping and other major industries. These effects will undoubtedly impact the ecologies of the land and the traditional way of life of the First Nations who occupy these lands.

In the summer of 1973, my brother Miklos and I and two other photographers received invitations to go north and live with the Cree to document their everyday lives. Eventually, we would return to urban centers with visual documentation that depicted the communities and show how the dam project would affect their way of life.

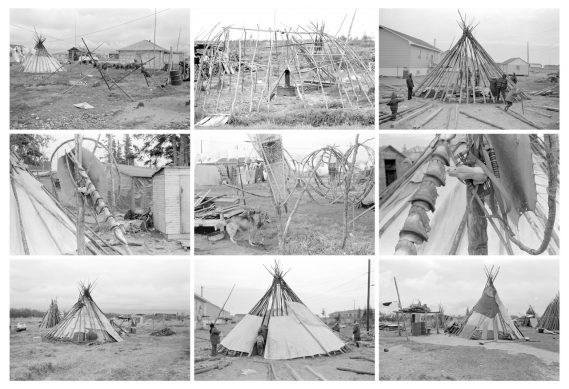

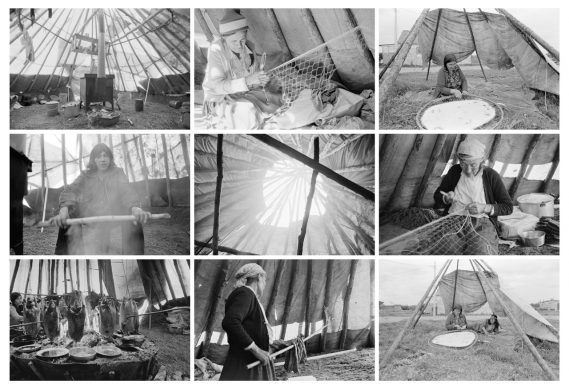

Here are tipi structures with fish drying, and beaver skin being stretched to dry in the sun. The upper left image has moss drying which the Cree used as disposable diapers. Women were in charge of constructing the tipis.

Smoke inside the tipis kept mosquitoes out. In the photo at lower left, Canadian geese cook for hours, while the grease collects in pans. At right, women repair fish nets, and a woman outside prepares a beaver pelt. The Hudson’s Bay Company—named after Henry Hudson who landed in Manhattan in the early 1600s—set up the northern fur trade. The Cree would deliver pelts to meeting sites, which became villages.

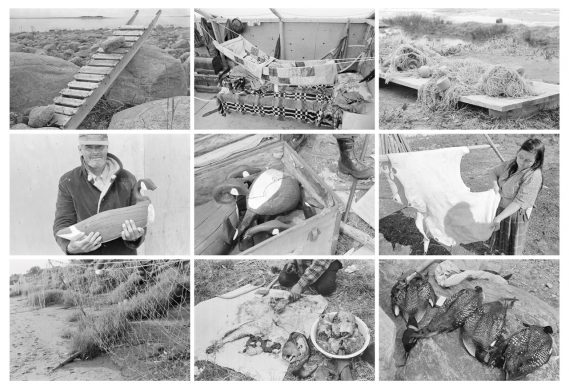

The Cree live off the land through fishing and hunting. In the photo on the left, Ray Spencer holds a goose decoy that he made. Ray was one of the legendary fiddle players in the north. In the 1600s, the Hudson’s Bay Company brought workers from northern Scotland, Orkney and the Shetland islands to Canada. These workers brought their culture and music and introduced it to the Cree. Today, Cree fiddlers are invited to Scotland as some of the few who can still play the original 17th-century Scottish music.

On the bottom right photographs, a woman shows her moose skin, while a man chops up moose skull for meat.

Housing at James Bay today looks very different from the above photographs. Now, the Cree all have contemporary suburban track housing. A few of the old houses, pictured above, remain and are now cared for as historical sites. The owners have refurnished them with original stoves, pans, gas lamps and other items particular to the former times.

Hudson’s Bay Company erected stone tombstones for their personnel. The Cree still have the white wooden fences around the graves, and they retain the practice of hanging animal furs, claws, skulls and other parts of the animal that cannot be used. It is a form of respect to the hunted animal.

I like how these images show the hybrid of Cree and contemporary culture. The Cree family here celebrates a birthday for a young man, and a father wears both a tie and headband.

These images show Cree dancing after a wedding, square dancing, and music played by the fiddler, Bobby Georgekish, accompanied by a guitarist. Dancing would continue all night.

Here are portraits of some of the elders of Rupert’s House, a community now renamed Waskaganish. I was asked to make the rounds with George Diamond, who translated for me. The elders only spoke the Cree language.

The other photographers and I arrived at the end of May in 1973. We were given a tipi to stay in, but it was too cold. So, I managed to stay with the family in the bottom center photo. We spent the night hanging out and slept in until we were woken by a record player. The family played Dolly Parton and Porter Wagoner. I had never heard of Dolly Parton at the time. No one was playing country in Montreal, but I immediately fell in love with the music. The song was the same every morning: “Daddy was an Old Time Preacher Man.”

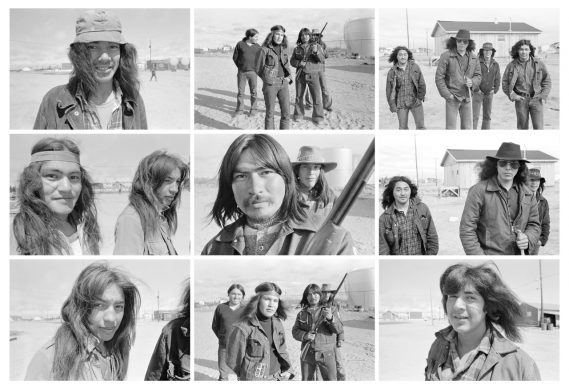

Gordon Neacappo is the one with the “Keep on Trucking” patch on his jean jacket. Today, he is the local radio DJ. This was my culture group—young unmarried men in their early 20s. A number of the young men were inspired by our visit to move to Montreal to take photography and video courses. Upon their return, they started businesses using these skills.

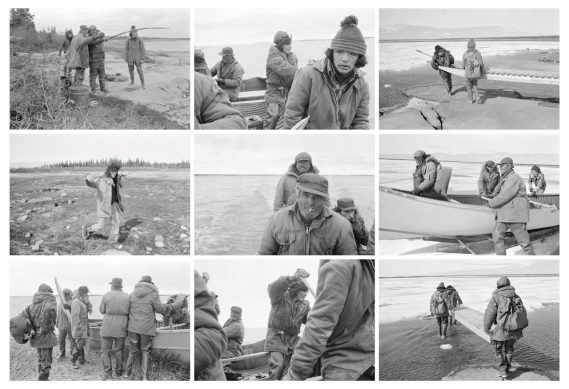

We went out to a hunting camp near the end of May when the ice was breaking up into large 100-foot pieces. Since the ice was so thick, the Cree would put a canoe on a sled and have everyone run across, so that the ice would not sink. When we got to the last chunk of ice we realized we were sinking, so we jumped into the canoe. The young men with the hat somehow managed to get water into his rubber boots and began to sink, and nearly drowned. We managed to hoist him up, even though the weight of the water in the boots made it very difficult.

Most of the canoes were made commercially, but I saw some photos of the Cree from around 1900 when they still made their canoes. They would peel birch bark off the trees and seal the pieces with pine sap.