Artist to Artist: eteam and Center for Land Use Interpretation

In our “Artist to Artist” series, we invite two Creative Capital artists whose art practices rhyme in some illuminating ways. Recently, we got the eteam (2009 Emerging Fields) duo and Matthew Coolidge from Center for Land Use Interpretation (2009 Emerging Fields) in our offices to talk about the anthropocene, what they’re working on lately, and of course, the implications of a pile of rocks. You can read the full transcript below or listen to the podcast above.

Franziska Lamprecht: I’m Franziska Lamprecht, part of the e-team.

Matthew Coolidge: I’m Matthew Coolidge, Center for Land Use Interpretation…guy. [laughter]

Hajoe Moderegger: Hajoe Moderegger, part of e-team, also guy.

Lamprecht: When I looked up the title of the lecture you will give tonight, I was like wow that’s the longest English word I’ve seen in a long time. Usually in German we have these words where you put two things together. I am trying to pronounce it: Anthro … Anthro … geomorphology?

Coolidge: Well you could say that, there are many ways to pronounce it. I tend to call it Anthropogeomorphology. Anthropo: human; Geo: earth; Morphology: shape. Very simple. A lot of people talk about “Anthropocene” as being the geologic period that we are in now. We don’t tend to use that word because we’re not really geologists, we’re—at the Center—more geomorphologists. So for us its always Anthropogeomorphology and there’s been absolutely no doubt about when it started appearing and what it is. It’s the stuff that’s created and shaped by humans, so its basically everything, everywhere. You could also say Anthropogeomorphology is the stuff that looks like humans, like the Old Man in the Mountain or Indian Head or even Mount Rushmore, for that matter. But that’s not what were talking about, the old man in the mountain perhaps is the best example of a more classical way of understanding anthropogeomorphology. Suggesting that “natural” landforms happened to assume human features or we attributed human features to those clearly non-human objects. And that’s a funny thing to think about too, but that’s not what were talking about.

Lamprecht: But in a metaphorical sense you are applying this idea to almost every landscape we are surrounded by.

Coolidge: Completely, I mean there isn’t a molecule on this earth that hasn’t been effected by humans, so therefore everything is anthropogeomorphology. So we gotta get busy here, because we’ve got a lot to cover.

Moderegger: There’s no nature in Germany anymore; everything’s been re-modeled and redone, so there is a term of Cultural Landscape. Does this term exist in English? I just translated it from German to English. In German it means at once the richness of the art and culture but it also relates to the culture that has been terraformed or transformed into something else. Is there a term in English that comes close to that?

Coolidge: Not that I’m aware of, there really should be. There should be an infinite number of words for our cultural physical landscape. We’ll get there eventually. Germans are often ahead of us here.

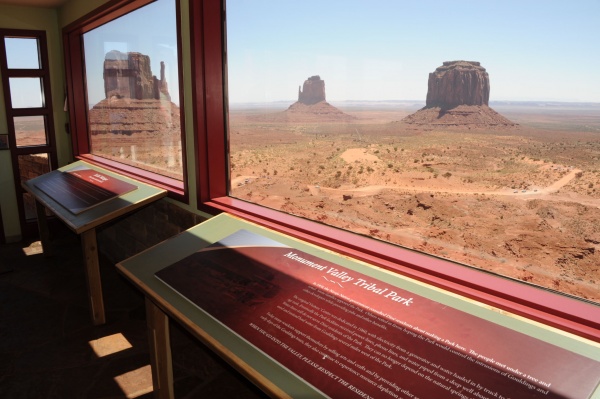

Moderegger: It’s also very weird because the term suggests something beautiful. You know culture always relates to the arts or something that serves the better, higher purpose. Yet in the context of the Cultural Landscape, its really something very violent, because it is transforming nature. You know, rivers are turned into canals to streamline for boating, so the whole landscape is turned around. I don’t know if that phenomenon exists on the same level in the US or if “nature” is more existent. It has all been touched but it feels like—we were just talking about Monument Valley, for example—in preparation for today’s talk. Two years ago for our last project, we drove through Monument Valley and we couldn’t stop. We had to drive through. The landscape was so immense that it didn’t make sense to stop at a particular place; it was a drive-through experience. And then reading in this magazine that said it was an untouched landscape or pristine.

Coolidge: There are no highways, no trains going through there, there was never a crossroads, it was a bypassed region in terms of the development of the west. Which has left it fairly unexploited in terms of the natural resources of the area, the mines that might otherwise be there that aren’t. It’s just this photograph-scape. And its also been under the purview of the natives for a long, long time. So they’ve been controlling the development. It’s a visual space, not a physical one, I guess is what we’re getting at in that article. It’s about looking, not touching, because as soon as you get up too close to the monuments, you can no longer see their forms; they sort of disappear, so you have to get back in order to ingest it. It is a drive-through or a walk-through experience. It’s not about being there, it’s about being near it and then moving on. It’s kind of interesting in that way, it’s a destination that you never really get to.

Lamprecht: This question of accessibility is interesting. The Grand Canyon could be the same kind of thing, where you can only look at it. But then there are tours to the bottom of the Canyon in which one can explore the details. I mean most people just look at it from above basically, but in Monument Valley, if someone would come up with a great tourist idea, wouldn’t it also be that could be explored on a smaller scale? Is there anything more required than an access point and a brochure that explains what is interesting about this place? People will come if you sell it right.

Coolidge: I think they could do this and they don’t want to. The value of the site for the people who actually own it and control it is in tourists not crawling all over the place. These are places intimate to them and their culture. I’m sure there are specific logs that can be measured in specific inches, where power resides within that massive landscape, but that is a Native American vocabulary not for us to exploit. So they’re not telling.

Moderegger: The drive-through aspect of Monument Valley is a perfect fit, then, for our time. It’s all about the length of the attention span, the experience, the mediated view, the cinematic perspective: you know, take my photograph, you’ve been there. It has the perfect balance, in a way, to keep the sacred sacred without actually providing access to it, and yet giving everyone what they need because what I need is a beautiful photograph. And I’ve been there, that’s all.

Lamprecht: It also reminds me of one of your book recommendations that I recently also looked at, and I was so excited about: Bad Luck Hot Rocks. It recounts the way people actually take a piece of petrified wood home and then they feel so bad about it that they send it back with a letter explaining why they feel bad and why they have to send it back. What do you think about this kind of phenomenon that people experience, what is it about these rocks that give bad karma to people?

Coolidge: Most of the notes suggest that people are doing so not just out of guilt, but out of a cause and effect. They’ve noticed a string of bad luck in their lives that they attribute to the rocks, potentially as either the source or a possible source, so they’re trying to correct the imbalance by sending the rock back. It’s very much a sense of guilt that is also practical. That sort of association of bad luck with the rocks is something that can be traced towards a notice on a bulletin board in the park exit that was there for a stretch that suggested that it was bad luck to take the rocks. Not everybody saw that note, but there’s that lore associated with the act. I believe that note has been gone for sometime from public purview. It’s interesting too, that the rocks—once they send them back—of course they’re out of context. So the park just puts them in a pile, in a service area, which has come to be known as the “conscience pile of rocks.”

Lamprecht: Do they actually exhibit the pile?

Coolidge: No they don’t. They’ll tell you where it is, but it’s not on the regular beaten track. It’s in a maintenance area. It’s a wonderful project that has got a lot to say in a very simple way.

Moderegger: It is interesting for us to read about these things because the last film project we did, was dealing with us going through Monument Valley, and then ending up on a piece of property that we bought in Arizona. And what we had found on the property was also petrified wood. It’s part of the same question. We took pieces of that petrified wood home with us, but so far we haven’t felt guilty about it. The land wasn’t part of the National Parks, so at least it didn’t feel like there was a spell over the wood.

Lamprecht: But we always assigned a certain value to these petrified rocks and instead of bad luck we had big hope in them, because we had bought the property on eBay, but we never got the deed. So we were basically ripped off. Our thinking was, ok so we found these petrified rocks, and they sell them everywhere. If we were to sell them in a gallery, maybe we could get our money back. But well, we’re still working on that part. [laughter].

There’s something about these little artifacts that you take out of a landscape that you are not supposed to, I mean we were a little bit in the same position because we were not supposed to take these rocks I guess, because the property didn’t belong to us officially, but we felt we had a right to take them in revenge or whatever. So that is our little petrified rock connection.

Coolidge: It’s interesting, that sense of proprietary-ness, that makes you compelled to take physical samples from a landscape. We collect a lot of signs at the Center. But we never take them down from where they were. We take signs that have fallen down and they’re broken, shot up, or no longer serving their function as the sign that was put up in the first place. I feel like that’s ok, but to take a sign that somebody else put there that’s saying something—no matter what your feelings are about what its saying—it’s wrong, it’s part of the landscape, and by taking it away you are interfering with the natural order of things in a way that wouldn’t necessarily give you bad luck, but that suggests there is something about your attitude that might give you bad luck. If you are compelled to do that here, you might be compelled to do other things in other ways that are also a little off. That’s maybe what the bad luck with the rocks is about. It’s indicating a flaw in character that’s certainly right on the fence in terms of it being an issue or not, but if you’ve got doubt then you begin to suspect yourself of overreaching to things that are beyond your domain. Even though it doesn’t hurt anybody directly or anything really, it’s just kind of the bigger picture. It’s also about responsibility as an anonymous citizen, one of 7 billion people. Your behavior isn’t really going to change the world but if you do it anyways, you know, it does change the world potentially. It has the potential to change things.

Lamprecht: In the Chinese tradition they have these scholar rocks. These specially formed, really interesting looking rocks that Chinese scholars put in front of them on their desk and then they meditate on the shape of the rock and it’s like a focus, thinking piece. So there’s something about the time that’s also within these objects I think. That adds an agency that is different than anything else: rocks last forever.

Moderegger: It’s also the shape, going back to the anthropogeomorphic form. There are so many rocks. I remember we drove through one area where they had all these—I forgot what they’re called—when the wind blows away and the water washes away everything else and just these pyramids are left standing and it looks like one stone sits on top of the other one but its just that the sediment has been washed away. I think the rock itself is the history, the wanting, but the shape is something else as well.

At a memorial to the artist Nancy Holt held on the Summer Solstice, more than a hundred people gathered to watch the setting sun line up in her sculpture Sun Tunnels, a large viewing device. Photo by Center for Land Use Interpretation

Coolidge: Rocks are sculptural, even if they’re not made by humans, which would suggest that they can’t be sculpture. That brings up an interesting notion that as soon as you say something is sculpture, you frame it from an anthropogenic point of view, a human point of view. That is enough to transform the object—even if it was not made by humans—into an artifact as opposed to a geofact. A geofact is a thing that exists pre-humans. An artifact exists only in the human realm. But you can take a geofact and change its context and it becomes an artifact. Which you know, archeologists would say, “No!” But I’m saying “Yes!” What do you guys think of that?

Lamprecht: What is your hypothesis?

Coolidge: That you can frame objects in a certain way and by changing the context you change their very nature and meaning. You can take a “natural” object and make it into an artificial one simply by changing the context and the way you see it. The object itself has no inherent integrity or, whatever you’d call it, because its context defines its meaning, not its material.

Lamprecht: If you leave things in their place and then extend the notion of the museum or the gallery by doing these bus tours, for example, and bringing people to this place and declaring it just conceptually as part of a museum. Maybe this is the closest way you can display a geofact as an artifact because everything else is an artifact the moment you take the object and put it into a gallery. It’s not a geofact any more because you have altered it the moment you touch it.

Coolidge: Perhaps we don’t even have to touch it to alter it. Just by framing it, pointing it out, you take it out of the non-human context. As soon as you single it out, it is transformed. What do you think?

Lamprecht: I think this is what you guys are doing at the Center.

Coolidge: I think you guys, as eteam, are doing it too. That’s why were here together.

Lamprecht: Part of what is so great about what you’re doing is that it is maybe the most harmless way to bring objects or things or places into a different context just by re-framing them. You are thereby changing the thinking about them instead of doing that thing where you take it and load it onto a truck and display it in different galleries. Did you arrive naturally at this methodology?

Coolidge: It couldn’t have been “natural” [laughter]. I don’t know how—trial and error maybe—or something. It’s more of a striping away of things, then a logical process, I’d say. It’s about that clairvoyant moment where you go, “Oh! Duh!” Just like Dorothy, you realize you’ve known all along you just haven’t allowed yourself to see. It’s just a matter of stripping away layers of confusion and obfuscation. I almost went to art school and then I saw what could happen. [laughter] And its great for some people but for me art school was just going to be more layers between seeing and believing.

Lamprecht: There’s something so optimistic about your descriptions of places and phenomena. They appear to be neutral, and not judgmental. But what I find so intriguing is that I know there must be more to the story than what you say and that is such a genius thing to do. This is where you get people to like things. The moment they want to find out more.

Coolidge: People are so buried in ideas. I like to take the bucket of ideas and dump it upside down and dump everything out and maybe use it as a pedestal to stand on to see above all the other buckets. I don’t know, but it’s useful to just start with the most fundamental shared space between people, which is the shared space between people. This tablecloth for example, this is what’s between us, this is our shared space.

Lamprecht: But to keep it simple, do you have to go to the place and spend time at the place or how do you, personally, build a relationship towards a place?

Coolidge: Well the ground itself, the physical place, is important. But less so than you’d think. Google Maps and Satellite View, is almost like being there in some ways. I was surprised. I personally feel less like I have to go everywhere, now that there is this quasi-objective universal view. I love USGS topographic maps for the same reason. They are single scale across the whole country: seven and a half minute quads that people use for hiking; that’s the base map of the USA as produced by the federal government. You can’t get any better resolution for the continent. These are the sanctioned federal views. As zoomed in and detailed as possible. And then Google Earth Maps with the Satellite View was sort of feeling like the same thing in a different way and maybe a little better. These tools don’t replace the need to be there physically, but they fill in some of that space. Not that it is reality, because none of it is reality, of course. It’s all this subjective interpretation.

Maybe it has to do with that site non-site thing, and I used to think this was a joke but now I think its real. There’s site: the place and you go and you’re there; then there’s the non-site: the physical samples and photographs that you construct in a different place, and that’s the non-site. And then Robert Smithson died in 1973, so he didn’t have the third site: the website. This is the compiling of the layers of information: the satellite views, photographs from all over the world, all converging around the Wikipedia, or whatever, all creating different iterations of that place. It is like a meta-space, a virtual space, a nonphysical space. It’s beyond the non-site. And it certainly isn’t the physical location itself, it’s a new terrain. But it’s that terrain of digital maps and Google Earth, where most of us are spending our time these days.

Moderegger: It’s a new space for some and not for others. I remember in 2002, when we first discovered the satellite images which were provided for free by the USGS. And then when Google Earth came out, the satellite images changed our view, which was the citizen view. The citizen/horizontal view changed in to this kind of governmental view, this overview. Now we have this look from above and we can zoom in on a certain area that we couldn’t do before. And that can be very satisfactory, because we are in control of that space at that very moment. That shift in perception was empowering and also disempowering at the same time. Because we are still not in control.

Coolidge: That is very much what your work is about, right? The virtual space versus the physical space, the representation of space through economic value and functionality, and space as a resource or space as a waste.

Read more Artist to Artist conversations here. You can also subscribe to Creative Capital podcasts through iTunes.