Yaelle Amir Curates Art Exhibition on Our Prison Systems

What would a prisoner’s dream home look like? Which news publications would an inmate subscribe to? To Shoot a Kite, an exhibition at the CUE Art Foundation on view through August 2, begins with questions like these and proceeds to open a world previously unknown to anyone who has never experienced the prison system. The show, organized by curator Yaelle Amir, examines several projects—including two by Creative Capital artists, Dread Scott and Laurie Jo Reynolds—that expose the “abject state of the incarcerated.” As an increasingly significant portion of the American population lives behind bars, an exhibition like this takes on obvious importance.

We spoke to Amir to get a better sense of her inspiration for the exhibition.

Alex Teplitzky: The essay you wrote for the show starts off with the character, Alex, from Sesame Street, whose father is incarcerated. Was it this character or something else that gave you the idea for an art show about prison inmates?

Yaelle Amir: I have been studying the issue of mass incarceration in the U.S. for a long while and had the idea of developing an exhibition about it a couple of years ago, after I became increasingly aware of the existence of many creative initiatives to raise awareness and provide services to prisoners, such as Jackie Sumell and Herman Wallace’s collaboration, Temporary Services, and Laurie Jo Reynolds’ various efforts through Tamms Year Ten to connect with incarcerated men and women. My knowledge of Alex from Sesame Street came later, through initial research for the exhibition. Discovering this character really brought this issue home for me, making it evermore clear that mass incarceration affects a broad segment of the American population.

Alex: The exhibition, including audio recordings, letters and documentaries, is so different from a gallery show you might see in neighboring Chelsea. Rather than using visual elements to captivate its audience, each artwork tells a story that begs the viewer to stand before it at length to really understand it. How do you hope these projects will affect people who have no knowledge of the prison system?

Yaelle: I find the works in this exhibition to be first and foremost educational. You cannot walk away from any of them without learning about the people who are incarcerated and the system as a whole. I cannot imagine someone spending time with these works and leaving the gallery indifferent to the issue. I hope this will encourage more individuals to call for a true break from the current judicial system, as it appears broken beyond repair and needs to be rebuilt with an emphasis on rehabilitation.

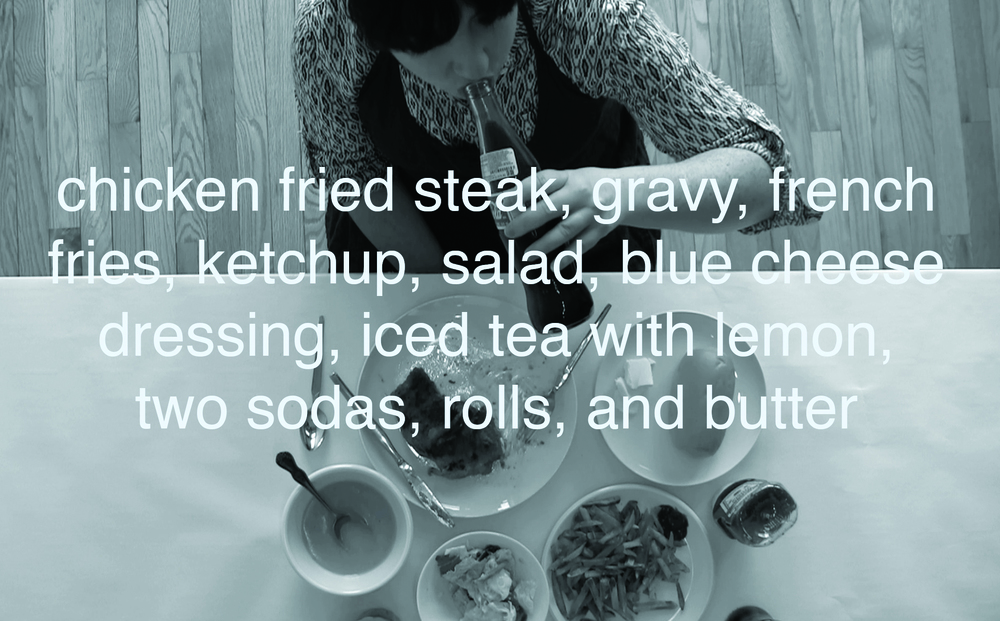

Lucky Pierre, “Final Meals,” 2002-present

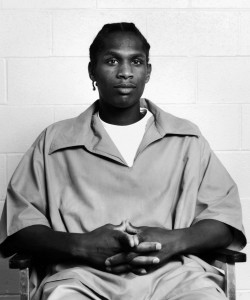

Alex: Lockdown by Dread Scott—a Creative Capital funded project—is a series of stunning black and white photographs with audio recording of the interviews he conducted with each inmate. You talk about how the project depicts a group of youth that are actually “acutely aware of how they got to the position they are in.” Can you tell me more specifically how Lockdown does this?

Yaelle: When you listen to the audio recording you hear the men speak about the mistakes they have made, their race and class background, and how their experiences are positioned in the general structure of our society. The self-awareness the men express is touching and, at times, humbling.

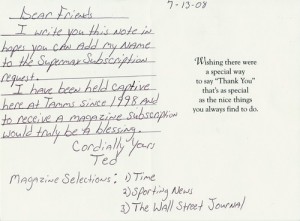

Alex: The exhibition also highlights the Tamms Year Ten campaign, started by Creative Capital artist Laurie Jo Reynolds and other activists to challenge the inhumane conditions at the Tamms Supermax prison in Illinois. I particularly loved the letters written by Tamms inmates to the Tamms Year Ten group, which promised subscriptions of news publications to inmates in permanent solitary confinement. The letters showed how hungry the prisoners were for access to information and education, and the various styles of their handwriting. Can you talk about the impact of the Tamms Year Ten project and what role it played in closing the Tamms prison?

Yaelle: The Tamms Year Ten campaign is an inspiring example of what persistent grassroots activism can accomplish. Six years of fighting for justice achieved what many may have thought to be an impossible outcome—the closing of a supermax prison in Illinois. I encourage people to read about the full process of the campaign on their website: http://www.yearten.org. The Supermax Subscriptions project—much like Tamms Year Ten’s Photo Requests from Solitary project that continues now in different locations—provided a service to the prisoners in solitary confinement who often felt all but forgotten. These initiatives reached beyond the sealed doors of Tamms Supermax prison and demonstrated to the incarcerated men that there are people on the outside who have identified the injustice they are enduring and would like to help alleviate their time in solitary in some way.

Alex: You proposed the concept for this exhibition to the CUE Art Foundation as part of a curatorial competition, and it was selected as the winning proposal by a prestigious jury that included Creative Capital artist Pablo Helguera (2005 Visual Arts). Do you feel like these competitions, where artists enter a role that traditionally directors or board members play, engender a higher caliber of curatorial practice and studies?

Yaelle: I think it is natural to have artists, curators and arts administrators play a central role in determining programming at an institution, and I believe that this is the case in many nonprofits these days. I feel that a diverse selection committee is essential in ensuring that programs reflect a broad intersection of ideas, and I am honored to have been the benefactor of such a process at CUE.

Yaelle Amir is an independent writer and curator based in Brooklyn, New York, focused on artistic practices engaged with social movements. “To Shoot a Kite” is on view at the CUE Art Foundation in New York through August 2.