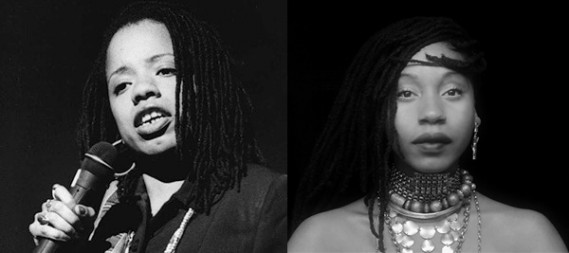

Artist to Artist: Queen GodIs Interviews Tracie Morris about Poetry, Performance and East New York

As part of our “Artist to Artist” interview series, Queen GodIs (2013 Performing Arts) and Tracie Morris (2000 Performing Arts) met up at the Brooklyn Museum to discuss commonalities in their work. The following is an excerpt from their conversation. You can listen online to the full podcast, or subscribe through iTunes.

Queen GodIs: This is Queen GodIs, Creative Capital grantee, 2013, with the honor of being with Tracie Morris, a Creative Capital grantee from…

Tracie Morris: The first class of Creative Capital—2000.

Queen: I’m excited. I think there are a lot of parallels that I’m interested in discovering between our work, and some new things. I’m excited to see what she’s up to in this time and figuring out what we’re doing now. I’m going to start with what I call a “check-in.” I think that before you start an interview and start with asking people questions about their business, you want to see what’s on their brain for the day. This check-in is actually inspired by a quote of yours that I heard in an interview that you did with Charles Bernstein. You said: “Our subconscious says things that our consciousness has to catch up to.” I thought that was an awesome statement—a profound statement—and one that rings true in so many ways. So for this check-in, it’s just a quick thought, word-association based on this year in America. So I’m going to throw out some words, and you just give me one or two words—short, simple, off-the-top, first things that come to mind.

Tracie: Calling Dr. Freud!

Queen: Here we go. Mandela.

Tracie: Exalted.

Queen: NSA.

Tracie: Typical.

Queen: GMO.

Tracie: Not having it.

Queen: A.D.D.

Tracie: Questionable diagnosis.

Queen: Drones.

Tracie: Droning.

Queen: Zimmerman.

Tracie: Murderer.

Queen: Gentrification.

Tracie: Global.

Queen: Jesus Christ.

Tracie: Superstar.

Queen: Kanye West.

Tracie: Gemini.

Queen: Gay marriage.

Tracie: Of course.

Queen: Jeffrey Wright.

Tracie: One of the greatest giants of acting.

Queen: Afrofuturism.

Tracie: Here.

Queen: Beyonce.

Tracie: Not hatin’.

Queen: The shift.

Tracie: Is constant.

Queen: And, last but not least: Brooklyn.

Tracie: Mecca.

Queen: Yes! Ladies and gentlemen, we are actually sitting in the lobby of the Brooklyn Museum, which is a special place for both of us because we both have ties to Brooklyn and its ever-changing state. So, I wanted to jump right into the first question that I have for you, which is a question that sparked my original Creative Capital project, which was inspired by the work of Octavia Butler and that did really explore what future means for me. And that question that I had to ask to get the body of that work, which I’m still developing, is: Who are you, and what were you before?

Tracie Morris performs It All Started at the University of Arizona in 2008

Tracie: I don’t know yet. I don’t think I have a definition for who I am; I’m still figuring that out. Who I was? Quite a few things, but one of the good things I think I was sick. And I’m just realizing, in the last five years or so, how being born sick was such a blessing for me and my life, weirdly. It was certainly anxiety-inducing for me and my family, especially when I was born and really small, but a lot of the stuff that is coming to fruition now is rooted in the fact that I was severely ill as a child. And now I’m an extremely healthy adult, but I was born at a turning point.

Queen: First of all, how do you define sick? I think that’s a really provocative idea.

Tracie: It’s true. I was born with a lot of physical challenges. Some of them were undiagnosable. I was pretty much touch-and-go for the first four years of my life. People didn’t expect me to live past infancy. So then I carried some of those problems with me until after puberty, and then I had a relapse as soon as I started college—probably somewhat induced by stress, but also because I was a frail person. So anyway, I won’t pull out my teeny tiny violin, I’ll just say that how it helped me was, I grew up in a really difficult neighborhood at a really difficult time—New York housing projects, difficult time—and being sick kept me from a lot of aspects of that environment that threw off a lot of people, like not being able to run around and play as much kept me out of the streets; it made me much more bookish; it made me explore my imagination. I think I learned how to empathize and try not to judge people by their bodies because my relationship with my body was so tenuous. And I think there’s also dark places I’m not as afraid to go in with my work because I’ve been in a lot of dark places. So, I think that that was helpful. The life that I’m living now was unimaginable to me when I was little. I mean, I literally couldn’t conceive of being an artist and being a professor. How’d that happen? That wasn’t something that I thought about.

Queen: Speaking of being bookish, what were some of the books that you acquired during those bouts of working through your sickness and having to be confined to certain spaces that other people weren’t? What were some of the books that you say—the titles that represent your life over the years? The ones that stand out the most.

Tracie: Oh, a lot of them were fantasies. Dr Seuss, then there was A Wrinkle in Time, The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit, Dune and The Martian Chronicles. All of those extremely fantastic worlds were on the public libraries as well as school libraries. And also politics. I remember reading about Nixon when I was really small. I really liked libraries. It was nothing for me to go into school and take out the absolute maximum on Friday and have read all of them by Monday, including a lot of crap like romances and stuff. (Laughs)

Tracie Morris performs Smokestack Lightning with Elliott Sharp at the Vision Festival 17 in 2012

Queen: Ohh romance novels! Let’s talk about that. Which one is your favorite and have there ever been any that influenced your writing?

Tracie: Well, of them are exactly the same. And I read a couple of dirty ones, too, snuck and read the dirty books that your friends would pass around. I think the only thing that they taught me was what really bad writing was. I could see an obvious plot point a mile away and get really bored with that. In terms of my romantic life, like everybody, those books are propaganda, for the most part, to disempower women, and I guess I saw a lot of contrast to that growing up in a tough neighborhood. So, probably there’s some aspect of that in my head somewhere.

Queen: Nothing has shown up in your writing or in your work?

Tracie: Probably it’s dystopia. I read a lot of poems that are about people having these false notions of romance that don’t make any sense. So that’s probably a pushback. I haven’t really though about it before.

Queen: What were you listening to this morning? CD player, iPod, iPad, whatever device you have for hearing…

Tracie: Well, it’s funny, this is not going to be a musical answer, but I was listening to the diction of Peter O’Toole. Peter O’Toole just passed away and I’m writing an essay on him. He had such an astounding voice. He was classically trained at RADA so he knows how to do the R.P. British thing. But he has this incredible diction so that even when he’s screaming and playing a maniac, which he does in a lot of roles, you can hear every letter, every single time! I watched three of my favorite films of his—Beckett, A Lion in Winter, and The Ruling Class—and he plays these wildly emotional shifts in these three…and I just love listening to the that way he speaks, the way that he uses his instrument. That’s what I was doing this morning: Peter O’Toole marathon.

Queen: High-five to the nerdism! That’s a first. I actually really appreciate it and I think it’s a perfect segue into my next question. I am here speaking to Tracie Morris: poet, thespian, academic, New York native, and, sound magician. She’s been dubbed a sound artist, a sound poet, in which the sound of the poem is just as significant as the content of the poem. What does it mean to be a sound poet? How do you embrace that term, and how does that term show up in your work?

Tracie: Well, you ask Jaap Blonk what he thinks, you ask Christian Bok what he thinks, you ask me what I think, and you ask the late Kurt Schwitters what he thinks and you get different answers. My relationship to sound poetry has to do with other ways of framing meaning that aren’t literally based. Every language has that—every language has onomatopoesis when things sound like what they mean. For me, sound poetry teases apart the meaning that is embedded with sound and separates that from literal meaning. So what I try to do is pull those things apart and then create a narrative arc from it. Now, not all sound poets are interested in the narrative arc. Some people just want to make sounds and leave them totally open to interpretation. But I like to use sound to make specific political points. I don’t want people to use language as an escape. Language is abstract, right? It only means what we ascribe to it. But people can sometimes get into, “OK, this word means this,” and then you start getting into that intellectual exercise. I want to get away from the intellectual and into the body.

Queen GodIs performs Black Madonna Medley (Excerpt from “Venus Transit Over Brooklyn) at the Merle Reskin Theater in Chicago

Queen: I can appreciate that. One of my first visceral lessons of that is I was performing in Rennes, France at the TransAtlantic Music Festival. It was my first time there. I was part of an ensemble that was spearheaded by a group called Les Nubians, who are Afro-European and French speaking. We were on stage performing poetry that we had written from this project—eight artists from the United States, eight artists from, I believe, Paris—and I was performing a poem that was a “signature poem” for me here in the United States. While I’m performing you couldn’t even hear a pin drop. There was no sound happening at all. I’m not used to that. Being a poet that was born and raised in the United States, you’re used to the “oohs” and the “aahs” and the snapping and the call-and-response on certain phrases, lines and words. And it was terrifying at first because I’m like, “Oh my goodness, am I doing something wrong?” Then at the end, the crowd erupts in this huge response, at the last line of the last verse. There were about 10,000 people there and I would say that a good 90% had no idea what I was talking about, at all. So they were really tuning into the sound and the feeling, the vibration and energy of the words. Some years later, as I was entertaining the idea of getting some poems translated into French, it’s a whole another…. One poem in multiple languages is not one poem; it becomes a whole world of poems. I want to ask you, have you ever had your work translated into other languages, and what did you discover from that process?

Tracie: No, I haven’t had them translated. I’ve used other languages. In my first chapbook, I had a bilingual poem; in my second one, I had a couple of poems that were in English, French, and various African languages, that is actually, I feel, somewhat untranslatable. My last book had sound poems. It has a CD. I don’t really put my sound poems on paper. No, I haven’t worked that much with translation, but I’ve read a bit about it, and I’ve read translations of other people’s stuff. It’s a whole other art. In the last ten years or so, NYSCA has started funding, under the category of creative work, translation as a separate category. I’ve read bad translations of poems, and it’s painful to read them.

Queen GodIs’ For Claire: Claire Huxtible Tribute

Queen: It can make a great writer seem like they’ve never written in their life, or it can make a mediocre writer seem like they are the best thing walking on the face of the earth. It really is amazing. When I was in South Africa, some of the poets that I met there were actually in turmoil because they felt like they could write good poetry in English but that was not their native tongue. I never understood a pain like this, because many of them actually did not know their native tongue because when they became teenagers—when they came of age and couldn’t decide where to be in the world—they had to make a choice: did they want to stay in the village or the bush and learn their traditional language from the elder who was the only person who could teach it to them, because it wasn’t something that schools had picked up and were able to teach, or did they want to move out and about, make money, see the world, and try to develop resources for their family? Many of them made the decision to see the world at the sacrifice of not knowing their native tongue and maybe never getting a chance to know it and, as a result, not being able to write poetry in their first language.

Tracie: And then you have people like Ngugi wa Thiong’o, who writes books, novels, only in Kikuyu because he’s like, “Ain’t gonna work in English. I’m not trying to write it in English, so it’s for Kikuyu people only.” And he’s fully, fully bilingual. He lives in near Los Angeles in Irvine. So, I think this leads to an issue which is: how much do you want to be liked? How much do you want to be accepted by people? How much do you want to be accessible? And I’m very ambivalent about those things, not just even in the mainstream, I mean just period.

Queen: On a scale of one to ten, how accessible are you as an artist?

Tracie: I have no clue.

Listen online to the full podcast (45 Minutes)

Subscribe to Creative Capital podcasts through iTunes