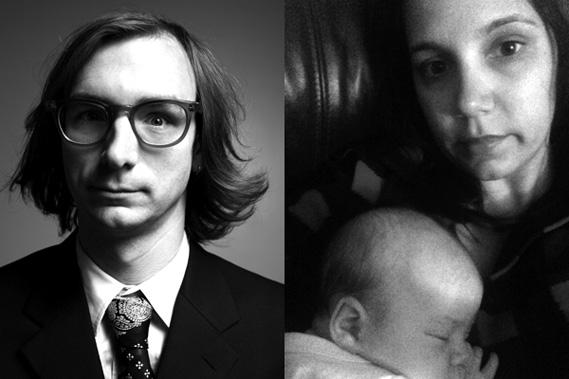

Artist to Artist: Neal Medlyn and Jessica Almasy Discuss America

Listen online to the podcast of this conversation, or subscribe through iTunes.

Neal Medlyn: Hey everybody. It’s me, Neal Medlyn. I’m here with Jessica Almasy from The TEAM at the Grey Dog and we’re going to talk to you about America for Creative Capital.

Jessica Almasy: Helloooo!

Neal: I was just thinking that we would get together because Jessica’s work is somewhat about America and I think that my work is about America, too. I don’t get asked about that very much. So, I wanted to talk about what it’s like to make work about America and have various experiences of people responding or not responding to it. I just wanted to have a wide-ranging and thought-provoking conversation about making work about America. [Laughs]

Jessica: Awesome. I’d like to start by giving a little context for where The Team is coming from. I’m part of the collaborative theater ensemble The Team, and we created a mission statement about ten years ago, which states that we make plays about America. So, if we’re succeeding, then that’s what we’re doing. Also, we had to create an acronym for legal purposes back in the day when we incorporated, so Team stands for Theater of the Emerging American Moment; so again, it’s right in the title. Our job is to think about what is happening right now. We gained our first traction in the UK at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival, so people really read our work as information from America being made by young Americans. We were like a specimen for them. I think there’s a really big difference when you’re out of context than when you’re ensconced in your own culture.

Neal, do you make a lot of your work in New York, or do you debut it here?

Neal: Yeah, it’s traveled a lot in the United States and a lot less in Europe, which is just happenstance in a way.

Jessica: When people see your work over the last few years, how often does the American commentary come up?

Neal: I think because it’s in the United States people separate it out. They feel like there is stuff about celebrity, but I guess for me, celebrity in and of itself…

Jessica: …is American.

Neal: Yeah! It’s like that whole kind of panicky, sweaty, super-intense thing about celebrities is uniquely American in my mind. Not that there aren’t pop stars everywhere else, but there’s something about the way that American celebrities seem to vibrate that says a lot about the national identity.

Jessica: Is that what drew you to it when you first started taking on these celebrity portraits and performance art pieces?

Neal: That was part of it. It was never so much just about the individual people. America as a concept and an artistic idea was super interesting to me. Because also I felt like, when I started out, there was a certain amount of protest to what I was doing. I felt like I saw lots of theater and poetry and stuff like that, and it all felt kind of like… I don’t know. This is not really fair to say that it wanted to be European, but there was a pretense at sophistication or at least a willful ignoring of all these things that were happening in America because they were “low.” And I started to realize that most of these things that were “low” or “beyond the pale,” like, you wouldn’t want to deal with them in an art context, were all just American things. Like our celebrities, domestic people, people in other parts of the country—all of that is not lofty enough to be the subject of art. So initially I wanted to be different than that. Lionel Richie is what I think is interesting about America. You know?

Highlight clip of Neal Medlyn’s Phil Collins/Genesis Show, “Coming In The Air Tonight”

It seems like more people are OK with incorporating pop culture and American-ness into the things that they’re doing, but certainly when I was in Texas it seemed like a crazy thing to do. Everybody was like, “We’re trying to do this thing from the fifties.” If it was theater, it was being Dadaist, or if it was writing it was being like Jack Kerouac. And I was like, “No no no I want to do something with the Madonna album that just came out.” [Laughs] What made you guys do that? To take America so explicitly as your topic?

Jessica: I think it was two-fold. One was where we came from, and one branch of it was a real appetite for meaning in what we were doing. At first, we were called “political physical theater,” which is not how we think of ourselves nor ever wanted to be categorized because of the very small rubric that puts you in.

Neal: Yeah. Who said that?

Jessica: I think it was when we had to be identified at the Edinburgh Fringe in the big booklet. You know. And we were, like, 24 or whatever so it was very physical and it was about America. It was political; we were drawing on political themes. It wasn’t a kitchen sink drama or a romance. But we had an appetite for meaning and we all formed the company because it wasn’t enough to have graduated from NYU and have taken these acting classes and then just go wait in line and try to put on these plays for an Equity contract that have already been done before. We just all hit that moment really quickly outside of school and simultaneously we were like, “OK, well, what’s important?” And I think the political part of it for some of us is the mythology of America, which is just such a great source material that you can draw so much from philosophically and emotionally. For some of us, it was that we were very politically minded and we wanted to be relevant in the moment. So, I think the reason we chose it was we wanted to do meaningful work, not just rhetorical work. Like, “Oh I’m going to put on this play,” versus, “I’m going to say this thing that might not change anything that anyone does outside the theater but they’re going to reflect on their country and on their citizenship in the theater with me.” That was our appetite for meaning.

And then the other hand was that our leader, Rachel Chavkin, who is the artistic director and really started the idea that we create a committed company, her parents are very political and she grew up in D.C. and they’re both attorneys and they also work for human rights and health care and they’re advocates. My parents are really big in politics in their local communities and my dad studied law. Jill, another company member, her dad is a social worker, and Kristen, her dad is a geologist and works a lot with the environment and got her really interested early on in the environment in our country and abroad. I could go and on. Jake grew up in Berkeley and his dad is an experimental publisher. So everyone was very invested in this country and I think this was our way of claiming that inheritance from our parents and examining that, and I think that’s why our company came together around America instead of just coming together around a bunch of kids who were hoping that they could just make art if they clung to a life raft. And I admire our twenty-something selves for doing that, you know? That’s pretty cool. I think we couldn’t just get it up for putting on a play for a play’s sake, we had to convince ourselves that it somehow needed to be talked about.

Video: Trailer for The TEAM’s “Mission Drift” (2011)

Neal: Yeah, I remember being very excited about that when I first became aware of you guys, just the idea of doing that was exciting to me because—I feel like part of it is just because America hasn’t been around for very long and, I didn’t even realize this until not that long ago, but going to museums and realizing there wasn’t much you could call “American art” for the first 100, 150 years because people would go to school in Europe and study art there—it was just a small market version of what was happening in London or Paris and there wasn’t, like, an indigenous form that separated and had its own thing for a really long time. And I sometimes feel that way still to a certain extent. What I found really exciting about what you guys do is that America is discussion-worthy in a lot of other ways than just Abu Ghraib, other than just American abuse.

Growing up in the South, I’m very used to the idea of being proud of where you are from and being ashamed of where you’re from at the same time, you know? There are all these problems, but it’s also kind of a great place.

Jessica: So there’s that parallel between you profiling or using the celebrity as a source and us kind of using the nation, at large, as a source because I think we think of it, of America, as—if you took all the countries of the world or continents or empires and put them as a family, America is this genius, spoiled teenager that is really running the show in a lot of ways. And other countries are both in love with it—“Oh we love our America. Look at it go! It has this energy that none of us exactly have right now.”—and also, we’re insulting, and we’re in the way. But there is that, like, celebrity vibration to the whole thing. I could say that America walks around as if it’s the celebrity of all the countries. It has that sense of self-importance, like, “Everything I do is relevant.”

I love that you that you used the word “panic” earlier. It makes me think of this sense of relevant panic. That the celebrity or the American thinks, “It has to be right now.” It has to be said, it has to be done, it has to be policed, it has to be stopped. It has to be seen, right now, by me, through me and there is a panic to it.

In our Creative Capital project, Primer for a Failed Superpower, we asked people in Britain; we’re going to ask academics and experts; people from different countries like Japan or Germany; we asked an artist from Greece: “What is your advice to America in terms of it learning how to stand down as the ideal, to grow up out of its teenage-ness and become one of the, like, working class of the world? (If that’s even possible.)” And the energy that comes from Japan or Britain or Greece is just, like, “Relax.” [Laughs] You know, just relax! Slow down. The hamburger doesn’t have to be that big. You can actually be satisfied with less. They don’t have the same panic. And even watching Egypt go through its crisis right now and the violence, I mean, there’s definitely a panic there but some of the people who are interviewed on the news seem quite calm. They are like, “This is what’s happening, we don’t have regrets about this, we have to deal with what’s happening.” And I feel like Americans sometimes have, and the celebrities always have, such a crisis of the mind. We’re kind of always saying, “OK, now what else do we need to deal with?”

But I’m curious, how is it dealing with celebrity head-on so much with your Pop Star Series? And also, being a performer, has there been anything interesting for you in terms of the dimensions of performance notoriety? Like, you’re a performer doing shows about larger-than-life performers who are these avatars for you, or you’re these avatars for them. Is there anything in there for you?

Neal: Yeah, there’s a lot in there for me. I feel like when people discuss post-modernism or things being a copy of things or all that Lacanian stuff about the signifiers having lost what they signify and all that… I mean, to me, that’s the way everything looks. It’s not an artistic critique of the world, it’s actually what the world looks like to me. America and James Brown or Michael Jackson, they seem like the same person. They’re separate but they’re the same and they move through and with each other. And when I join into it I am a part of it.

But I also feel like it’s because when I was in college and I would go over to somebody’s dorm room to smoke pot and then they put on something like Sublime, or something like that. And then they’re looking at themselves in the mirror with their braided belt, smoking a joint and singing this song written by somebody in Southern California who they don’t know, they don’t have the same lives, they’re not the same person at all as this little fellow who’s smoking weed. I just remember sitting in this dorm and feeling, “My God, there’s so much about that, that thing, that exchange.” He’s not that person, he doesn’t need to be that person but yet he is that person.

Or you go to a Beyonce concert and there’s 40 year old men, or me, that are there in the audience and mean every single word of all the songs…Or when I was a kid and would listen to Public Enemy or NWA—that’s obviously a wildly different life than what I actually had, but those songs were very important to me. And when I sang those songs, it wasn’t ironic that I was singing those songs because I have this different life, it was like I felt and believed those things as I was saying them and they were entering me and becoming a part of me.

And I feel like, growing up Pentecostal, it was like that. At least the way I grew up, the Christianity that I grew up with, you couldn’t separate the three people. Like they’re three people but they’re not, they’re all one thing. There’s only one God but he’s got three persons. And in Pentecostal stuff, the Holy Spirit enters your body and is sort of like your constant companion, so you are sort of possessed by this thing that is one of the personhoods of this thing, but it’s only one God… So there’s all this confusion of where does everybody stop and start?

So I feel like, for me, it has always been easy to see everything as one thing, if I want, or break it down, Russian doll style, “Oh this is inside of this and this is inside of this.”

When I started out and there was no one around and nobody saw the shows, they kind of did exist more inside my own head or inside my notebook. But now that I’ve done them, and, like Kanye West seeing the Kanye West show, it’s like that starts to become a part of the conversation I’m having.

That sort of stuff is exciting for me because I never wanted to feel outside of—honestly, I just don’t know how to feel outside of it. I don’t know how to remove myself in a “commentary” type of way about America or about a particular star, it gets so mixed up… It’s codependent, I guess. [Laughs]

Jessica: Spiritually codependent.

Neal: [Laughs] I don’t know where I stop and you begin!

Jessica: So this is a series that’s been going on for a while that you’re culminating with the show King at The Kitchen, and then hopefully you’ll get to do cumulatively as one piece. Then, where does your work go next, in terms of all these ideas?

Neal: I think it all turns into Champagne Jerry.

Jessica: Can you talk more about Champagne Jerry? I haven’t seen him yet.

Neal: Oh. Yeah, well, it’s just this: I’ve been writing all these hip hop songs and I think the idea of who I am inside those songs is a lot the same as what I’ve been doing in my previous shows, but it’s more set up like a music concert. I mean, it is a music concert. But there are all these characters, like one of the people in my onstage entourage is the Ghost of Champagne Past and she sort of haunts me occasionally, we have a song together. A lot of the things that I picked up from Beyonce or Phil Collins or wherever, they are in this show except they’re mine now. Or I’m deciding to look at it like that. All these other people were opening acts for Champagne Jerry. And there are ways I’m thinking about making that really explicit, like drawing a line between those things. Which feels kind of crazy, but on the other hand, I’m so into this thing of creating myths that I’m not going to be other stars or use other stars to make those myths any more. I’m going to be the star making the myth that I’m working with. That’s the direction I’m going.

Because you’re all doing lots of different things now, what do you guys feel is the future of the Team? Does it change as you guys change, given the fact like you were saying that it all started when you were really young and at a specific place in your life and now you’re at a different place? Is that reflected in the group and what you want to do with it? Or is the group, the Team, still conceptually intact?

Jessica: I think the company works as a good metaphor for the country, for democracy. We have these separate states that came together because we really needed to form something in opposition to something else, to an old idea. We have really different needs. Even from the beginning, the first couple of years, you’re already arguing for your vision of what the work wants to be. But I believe that we’ll stay together and keep working, and I believe that we’ll be satisfied and dissatisfied. I can only speak for myself but I feel like I’m more and differently interested in the idea of America. I think, fundamentally, we all really care and we all want to keep going and we will. And it’ll just be a continual series of congresses and voting and the whole vibe. And sometimes we’ll be in a flush era and sometimes we’ll, you know, struggle, but I have definitely found it a worthy investment.

Neal: Have you ever heard of that thing, that “philogyny recapitulates ontogeny” oh wait it’s the other way around “ontogeny recapitulates philogyny”?

Jessica: I don’t know.

Neal: Basically the idea—which is completely debunked but I really like the metaphor a lot—is that when you’re a zygote, your development recapitulates the entire history of the species. You start out as a single-celled organism, then you become a multi-celled organism, then you become a fish-like organism, etc. And that’s not a real biological imperative or anything, but it’s interesting. So it’s fascinating to me that you guys as a group might be recapitulating the history of the country in this way.

Jessica: That’s a rich image.

We’re doing this play about punk rock and we did this play that had to do with the antebellum south and we did a play that had a lot to do with conservative Kansas, and I think each of those plays also made us deal with different aspects of ourselves and then changed us as a group and we’re different afterward. And it’s not something that we just put on and recite. It’s something we have to walk through and be angry about or be happy about or disagree about. And it changes our relationships to each other. And so in that way, yeah, we get to change each other through trying on different aspects of being American.

Neal: I’m also curious about the audience’s role in that, because the people you get feedback from, or press, or just sort of the general perception is an interesting part of that. ‘Cause it’s supposed to not change you, but just its existence adds all these things, particularly with you guys doing stuff a lot in the UK. What is that like? Sort of like you’re delivering a message or representing a message? It’s like the circus coming to town or something like…

Jessica: [British accent] “Oh! We get to see the pandas from China.” Or “Oh! We get to see the youth from America.” It’s both what we’re actually saying, and also just us being in the room with them and them being like, “Oh, look at how they’re handling this…”

Neal: [Laughing] “How you move your hands that way…it’s so American…

Jessica: [Laughs] Yeah, and I think there’s a real generosity and space in that, and then there’s also this sort of uber-complimentariness that you get when you go to your old aunt’s house and she’s like, “Oooooh, you’re just so wonderful!” Whereas if you went into an agent’s office and did the same little play that you did for your aunt, the agents might be like, “Well, let’s talk about what’s structurally not working with this play.”

Neal: “It’s sort of sagging in the middle.

Jessica: So, America is more about performing for the agents. I think that another advantage is that the British press especially are really great about looking at the ideas of the play and being really open to the way we’re structuring our plays to talk about the ideas. So instead of getting stuck on the popularity contest that can happen in American press of like, “I liked it,” “I didn’t,” “It was long,” “It was not long enough,” or whatever, they’re like, “OK, so this is the structure they’re using. Why are they using it? Why did they put all this time into talking about this idea? What can we see Americans trying to talk about?” And I think Americans take each other for granted in that way because we’re all in the wallpaper of ourselves all the time.

Neal: And also the British, I feel, they also excel at Criticism with a capital C. They’re just so good at it. Sometimes I’ll just read the London Review of Books. I won’t have any idea of what book they’re talking about, but the language is just so amazing, it’s just really a next level kind of experience. But that feels like what we were saying before about America, and I feel like it extends to the press as well. It’s like on CNN, where they can’t even say the beginning of a story without being like, “I don’t really know that much about credit default swaps bu-u-ut today, the SEC…” Why do you have to qualify it like that?

Jessica: The thing you were just saying about the criticism, that’s something that, in thinking about a practical relationship between America and the work we’re making, I would really love to see more practical, common, frequent, mass-marketed actual discussion of the ideas in the plays and the art—wondering what is relevant, what makes a story relevant. There are a lot of plays I go see or pieces of work where I might not actually care for my experience of watching the work, but if I start to really talk to myself about what was in the work, the ideas, it’s really relevant and reminds me why it was worthwhile to be a part of that. I hope that there’s more printed in that way.

Neal: Yeah I hope so, too. It feels like such a transitional moment and I feel like, hopefully, it will get to this place where there’s more being written, and there’s more space for it. I feel like the media companies that are around have been so reluctant and slow to switch over and develop other things and what they do have is so separate from their their overall voice. I also wonder if some of it is just kinda a cultural moment right now where people like. I drove past someplace the other day and there were like 75 people out front of some bakery or something like that? And I really love food but it feels like the cultural conversation right now is about food and not about art. That energy that has been about camping out and trying to get into this show, and having arguments with your friends about this or that show being good or bad or worthwhile, or this person’s all washed up or this person’s full of hype or this person’s great, an undiscovered gem or whatever, is now about cronuts.

Jessica: Yeah that’s a great point. When you get booked for different events, do you sometimes get booked where your work is being read on the most opposite level than we’re talking about, like where they’re like, “Oh, isn’t this just so fun and hip and he’s gonna be doing something with the Insane Clown Posse” or “It’s so snarky and ironic that he’s doing um whatsherface Britney, or whatever,” and then they book you because they wanna drink fancy drinks and watch you do that, or does everybody get that there’s something else going on?

Video: Neal Medlyn, “Wicked Clown Love,” highlight reel of performance at The Kitchen, 2012

Neal: I think they do—they usually do afterward. That happened with the Insane Clown Posse thing. I’m almost positive this one thing that got written about it, they came into it thinking it was going to be something else and then saw a rehearsal and were like, “Oh, whoa,” so then all we talked about was how it was not that thing. I don’t know what percentage, but I definitely feel like I’ve got booked places before and I’ve walked out on stage and the audience was there for something slightly different than what was going to happen. I feel like that probably happens on a relatively regular basis. But I’ve done some things I’ve liked because I was like, “Oh, well they’re definitely going to think this, so I’ll start it out this way,” and either play into it or not play into it for a while, and then flip it or something, because a lot of the times it’s been material that people have feelings about already.

Jessica: Well, you’re working with such potent mass images.

Neal: It actually took me a while to realize how people were reading it, I think, because I was alone so much. I probably did shows for five years? Six years? In front of between two and 15 people, so it was a long period of time where I was doing whatever I wanted with the material and there was no conversation really coming back at me about what was happening.

Jessica: That was probably positive in a way—I mean either way has positive effects, if you have a lot of people watching from the get-go or if you have this really intimate almost transaction, versus performance…

Neal: Definitely. At the time I didn’t like it because it was so much work and no one saw it. Everybody has that thing and it’s brutal, but it is funny to later on start to become somewhat nostalgic for it and be like, “Oh, that was kind of awesome and we just did that and we just slapped it together and nobody saw it, but whatever.”

Jessica: It’s hard, it’s hard. It takes a lotta spinal fluid to get through that.

Neal: Yeah.

Jessica: This is sort of a non-sequitor, but it reminds me of—on the celebrity front—one of the first shows I did with The TEAM, when we went to Scotland for the first time, was a solo show that I did with Rachel [Chavkin], and one of the most recognizable characters I played in the solo show was Richard Nixon. But now I’m looking back and I’m like, “Wow, I was like a 25 year old girl playing Richard Nixon for like, three people, in Scotland.” And then it reminds me of another time—many years later when we had a much bigger audience and a lot of support—when I was playing Margaret Mitchell. Usually in Scotland when you do your first showing it’s like at 11am or something and it’s like a half price ticket, so it’s mostly senior citizens. And they all had read what the play was, and I guess someone sets it up that I’m entering and I’m the woman who wrote Gone with the Wind or whatever, and I remember I walked out and they clapped for me! Because I was Margaret Mitchell. It was one of the coolest, most enlightening moments for me where I realized that the audience had so much to do with everything that was seen, because they really brought this hologram of this person that was alive when they were alive when they were younger. I just stood there—I was the pole and they just projected this avatar onto me. And applauded for it. And I felt excited for them that they were getting to see her. I didn’t feel that way in any of the other performances because the audience wasn’t conspiring as a group to see that celebrity. So what you were talking about earlier, this idea of channeling celebrity and, like, things not being separate… In that moment, I wasn’t acting like Margaret Mitchell, we were, like, just dealing with her, all of us together, and that’s pretty cool.

Video: The TEAM’s “Architecting” (2008)

Neal: I find all that stuff super fascinating—that place where like drag is not about impersonation or something like that. It’s an alchemical type thing that happens with the audience. It almost can’t exist without the audience because it needs to be seen. If you are at home dressed as Margaret Mitchell you’re not Margaret Mitchell.

The other thing I think is sort of interesting about America in general and about a lot of different artists, like R Kelly and the Insane Clown Posse in particular, that becomes this whole conversation is whether they know that it’s funny. I think that whole idea is very foreign to me but fascinating, because it’s this whole idea that your response to what they’re doing somehow supersedes what they meant for it to be, and then it’s not a conversation, y’know? Because I think most people figure that there’s an artist who creates a thing and they say what it is, and your responsibility is to get it or not get it. This must happen with you guys a lot given the fact that you’re talking about such a huge topic, like an entire country with a long history and a lot of different aspects and parts and millions of different individual people who make it up…

Jessica: People in the audience have more determining power than I think they’re reminded of. I watched the play learning itself while being performed for other people, and then some days, the play couldn’t be just anything else but what those four people in the audience insisted they saw, and they only let us know what they saw by their response or lack of it. Then the next night it was this whole other thing because of the way the people saw it. We didn’t change the game-plan. So it really blew my mind in terms of—yeah, how much you might try to control it and how much you can’t…

Neal: And—I mean, maybe this isn’t true—but have you guys done very much of The TEAM stuff in America? Is the reaction really wildly different? The feeling of it…

Jessica: I think the feeling is different. The first thing that comes to mind is when we did a show in 2006 at PS 122 called Particularly in the Heartland, which was a nice success in the UK. The play opens with all of us, preset, singing American songs, and inviting the audience to sing them with us—everything from “This Land Is Your Land” to “Bye Bye Miss American Pie,” or any rock song with America in it. And when we did it in the East Village, it felt really vulnerable? Like people thought we were joking. It was like being the earnest kid in high school.

Versus in Scotland—it doesn’t mean that they all wanted to sing along or something, but they were just like, “Oh, here’s some Americans being American and they’re enthusiastic,” but being an enthusiastic American in New York City was not appreciated.

Neal: I always felt like corniness is such a thing that makes people really freaked, particularly in New York, particularly about anything artistic. It seems to make people kinda grossed out or upset, like, “How dare you!”

Jessica: “How dare you pull us back there when we’ve all gotten through that to this wiser thing? We live in New York.” And it’s like, yeah, we didn’t wanna be corny but we did wanna mean what we said.

Neal: But if you had come out on stage and cut your arm or peed on the floor or something like that, that seems like totally within bounds—I feel like you would feel less of that weird energy coming back from the audience than you would if you were…

Jessica: …being happy and…

Neal: …singing “This Land is Your Land”…

Jessica: …singing about America, yeah.

Neal: That’s what makes people feel upset, which is always fascinating to me because living in a more urbane or sophisticated place as you are, there is this assumption that it is impossible to make anybody feel anything uncomfortable for real because they’re just too smart for that. I found in other parts of the country it feels like you can get away with some of that stuff, but you can’t get away with anything that’s sexy. It just doesn’t have a place in anything that’s artistic. It really starts to freak people out. So I’m just sort of fascinated by that and by how the more intelligent you are, the less jingoistic, the less enthusiastic you are about the United States.

Video: Trailer for The TEAM’s “RoosevElvis”

Jessica: I think the sexual component of America and of the performance talk is really relevant and it feels like that’s a place that we’re just entering into in our work. I think the celebrities are so fetishized and so sexualized so I feel like that’s all over your stuff whether you are addressing it or not it’s just in there, but sexuality hasn’t really been a major color palette in our work. When we think of what we’re addressing it usually falls low on the on the totem pole. But this newest piece that we’re doing, RoosevElvis, is a two-person piece—it’s two women—it has a lot to do with gender. One of the characters is a lesbian and is living in a part of the country where that’s not supposed to be talked about, and she’s having this identification with Elvis, so that’s her gender. It’s really one of the first times sexuality rose on the totem pole inherently, so it’ll be interesting to see how we bring that into our very genuine American theatre, because we’re not we’re not being television about it; the writing is still genuine and simple and clear, and like all of our other plays, there’s really no tricks. We’re not winking at all.

Neal: Yeah that’s interesting. I think it’s really interesting, too, what you’re saying that you guys don’t wink a lot. Maybe this isn’t an accurate statement, but I feel like in a lot of “downtown theatre,” there is that aspect of going back and forth between winking a lot, or overtly winking as a style and other wacky elements. It’s part of a language choice or something. So it’s interesting to me that you guys don’t do it that much. I find sincerity in going about things in that way so fascinating because it just seems like it feels really weird when you’re dealing with “America” or “celebrity” or any of those types of things, it feels radical in a way to just be sincere about something. Of things you can do that are wild, it’s weird that that’s something that feels so dangerous.

Jessica: Yeah.

Neal: I don’t know. It’s interesting.

Jessica: Definitely… Well, I think lunch is done. Thanks for a great talk, Neal!

Neal: Yeah, thank you. That was a lotta fun!

Jessica: OK. Bye!

Listen online to the podcast of this conversation, or subscribe through iTunes.

Neal Medlyn’s “King,” the culmination of his Pop Star Series, premieres at The Kitchen in New York ,October 23-26, 2013. The TEAM’s “RoosevElvis” premies at The Bushwick Starr in Brooklyn, October 8 – November 3, 2013.