Artist to Artist: John Sutton and Juan William Chávez Talk Public Space, Environmental Remediation and the Challenges of Community-Based Projects

John Sutton: So, a little bit of background to start: I’m a 2008 Visual Arts grantee—one third of the group SuttonBeresCuller—and I’ve returned to the Creative Capital Artist Retreat for the last couple of years as an artist advisor and consultant. At this year’s Retreat, [Creative Capital staff] Lisa Dent and Jenny Gill introduced us and said that we had to chat because our projects have a lot of parallels and they thought that we could learn from each other.

Juan William Chávez: Great to talk to you! I guess we can start by just describing our projects.

Sutton: Okay. SuttonBeresCuller does a lot of different kinds of work, but our Creative Capital project, Mini Mart City Park, is an ongoing project intent on the creative reuse, revitalization and remediation of former small-site gas stations. Right now, we’re focused on a site in Seattle’s Georgetown neighborhood. Like many of these former gas station sites, it’s heavily contaminated, and ultimately we want to clean it up and turn it in to a pocket park, community center and public sculpture, and gift it to the city, for the site to become part of the parks department. Everybody’s really interested but nobody wants to take on the environmental issues.

When the three of us started this, we leased the property, with an option to purchase. We went through four years of environmental assessments and studies, created a strategic action plan and finally decided that the only way forward was to purchase the property and take on that liability, because we weren’t eligible for certain funding being a leaseholder. We formed a separate nonprofit organization, to purchase the property and further develop this project, and it’s going to allow us to, hopefully, raise the funds to do the remediation, and to challenge the EPA to change policy on how these sites are addressed.

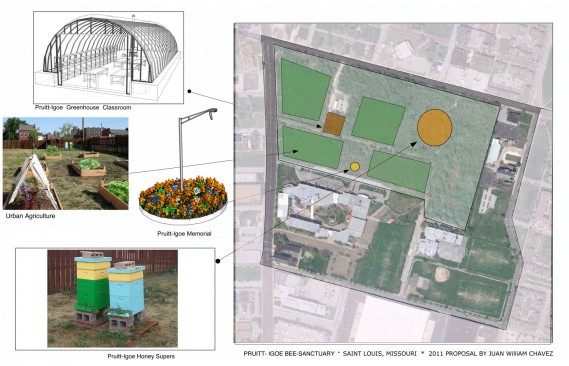

Chávez: That’s great. So I’m a 2013 Emerging Fields grantee, and my Creative Capital project is called the Pruitt-Igoe Bee Sanctuary. The Pruitt-Igeo Bee Sanctuary is a public proposal to the city of Saint Louis that aims to transform the urban forest where the Pruitt-Igoe housing development once stood into a public space that cultivates community through beekeeping and urban agriculture. The project draws parallels to the depleting population of bees (colony collapse disorder) and the challenges of post industrial “shrinking cities.” We hope to redirect the conversation surrounding Pruitt-Igoe by developing creative strategies that both memorialize the past and provide opportunity for the future. That way Pruitt-Igoe can end on a positive note by transforming one of the worst failures of public housing into a leading example of revitalization.

Sutton: In my brief conversation with you at the Retreat, I was really excited about your project and all of the things that it’s encompassing and the parallels with what I’ve been discovering in my own practice, working with different agencies, brownfield remediation of public land and trying to transform properties into public space. So I was thinking we could talk about some of those parallels, and also the ways that our projects have different challenges.

Both of our projects are trying to repurpose former sites for a community-oriented redevelopment project, whether that redevelopment is public space, green space, open space—the bee sanctuary takes a lot of that into account, same with our project. But I think they overlap not only in the intended outcomes and audience, but also in the practice of making that happen: the necessary business structure; since your site is also a brownfield, remediation funding sources—different ways to make that happen. Ultimately, I think where your project has the biggest hurdles to overcome, at least in my understanding right now, is in actually gaining control of the site. If I’m correct in understanding, you have no legitimate access, right?

Chávez: Yes, that’s a good starting point, which is: both of our projects deal with a site, and before you can activate a site you have to have access to it. So, I started going onto the Pruitt-Igoe site in 2010, just kind of documenting it, creating some films. Just documenting the forest itself. And then through that process I started to ask more questions about the history of Pruitt-Igoe, how Pruitt-Igoe was designed and made for a community, and now Pruitt-Igoe is nature, so what community can actually live there? For me, that community was bees.

In 2012, I did a site-specific installation of these beehives that referred to Minoru Yamasaki’s design of the original public housing buildings, so that was kind of the beginning of the project in terms of how I went into the site and started to think about it. What came next was researching the idea—if there was a preexisting model of bees in pubic space, where was that and how did it function? I found an example in Paris, France, at the Luxembourg Gardens.

The other step was to develop a pilot project, to do a test run of what this site would look like. I run a nonprofit, the Northside Workshop, that’s very close to the Pruitt-Igoe site, where, for the last two years, we’ve implemented a small bee sanctuary in an urban garden, and I’ve been leading workshops of creative strategies for activating vacant spaces for urban gardening and beekeeping, and then working with the community. So, the Creative Capital Retreat really came at the right time for me, and especially being paired up with you, because I’m thinking about the next steps: How can I take this from research to pilot? How to create the actual steps? The Retreat definitely sparked a new direction with a bigger picture.

Sutton: Great! So there are clear parallels, but the details are not quite the same. I mean, for one, the site you’re interested in working with is enormous—33 acres—and ours is 5,300 square feet—a small site. Seattle is very much a boom-town, at least in terms of real estate, which is very precious and it’s hard to find available space. So part of the idea is that we were looking at sites that nobody else wanted to touch, because there wasn’t any economic incentive to clean them up. For example, in fair market, if it didn’t have any of the environmental issues, our property would probably be worth $250,000 for its size and the neighborhood that it’s in, but it’s probably going to cost well over $2 million to clean it up. So we’re kind of taking on something that nobody else wants. With your project, it’s a little different story because of the size of the site and potential interest for developers, but it’s been sitting in—I don’t want to say “neglect” because nature’s taken root—but it’s been vacant for about 30 years, right?

Chávez: Yeah, the Pruitt-Igoe site is owned by the city of St. Louis; it does have some interest from local developers. So, when I came back from the Retreat, the first thing I started working on was drafting a strategic action plan for developing the site, creating partnerships, working with landscape architects to come up with a visual of what this thing could possibly look like, how much it would cost to manage it, the details of building a trust that could help sustain the project, and then working with people who can actually help me initiate and negotiate a conversation with the city and local developers. That’s what we’re currently focusing on: building partnerships and creating a strategic action plan that we can present to potential stakeholders, developers, the city, to get people on board about the project and help with fundraising and marketing, and release a citywide campaign for this project—definitely getting people involved to help support the idea. Those partnerships and those conversations just help advance the project, and it starts to seem more that it’s doable rather than a kind of conceptual proposal.

I think how the site is managed is definitely something we’re trying to figure out right now. That’s, like, the biggest thing. Once you do have access to the land, what do you do with it? This huge chunk of land… And my philosophy is kind of: A space is a space, but you have to activate it with programming. That’s how a space can really seek its full, full potential. And with the current economic climate in St. Louis, the city taking on any type of responsibility of managing another park is something that’s probably not going to happen. So, I’m trying to find alternatives, alternative structures, definitely creating a trust or an endowment, connecting several nonprofits that could help program the site, and then have an overall entity that oversees the day-to-day operations of the site. In that respect, we’re still in the very, very beginning phases. At the end of the day, my goal is that this project might start as an individual artist talking about it, but hopefully it ends with a group of people, because it’s going to take a huge group effort for the space to reach its full, maximum potential.

Public space is definitely a huge challenge right now, in the Midwest, I think, especially because of the lack of funding to manage these spaces. So you see a lot of public spaces actually being developed through private entities, which—you know, they have their pluses and minuses, too. So it’s just really trying to find a middle ground of how you can develop a public space with potential private investors, or universities, or nonprofits, all coming together and having input.

Sutton: Yeah, I think the different socio-economic aspects of our cities are going to have a big impact on how things go. I like that it’s starting off as an idea, and how does that idea get out there into the world and actually start to become a space? How do you program that? In our project, we’re hoping that the space eventually goes to the city, but that is just one outcome. I think, with your project and with ours, it’s really important moving forward, and when you’re developing a strategic action plan, that you retain some fluidity to any potential outcome; that things can change along the way; that you need to be open to finding new partnerships or alternative funding sources.. I’d be interested if you could see partnering with a developer that has an economic incentive to develop the site, but you retain a portion of it, so that you’re not having competing strategies but maybe finding a way to make these two things work together.

Chávez: Definitely. We’re hoping that the strategic plan highlights other potential things that could serve multiple layers, besides the idea, the economic impact, how much it’s going to cost to clean the site… The site could be used not just for a bee sanctuary but also to basically serve as a huge rain garden for the city, or for a big portion of the city, to help alleviate some of the overflow from our sewer system getting overwhelmed by stormwater.

So going back to what you were saying, it’s been really interesting, trying to find mutual ground with the city or developers. You really have to have the fluidity of the artist, and the problem-solving approach that artists tend to have is that when you get information, you can quickly transform it or incorporate it into the overall project. Which is exciting, because what I think gets big ideas off the ground are people that have a stake in it. The more people have a stake in it, that are benefitting from it, that have a say in a project, then it’s more of a “raising of the barn” kind of experience than a “this is a big quick fix idea, this is a good idea, this could help.” It’s more like, this idea has the potential of aiding and helping on all of these levels with multiple groups. In a way (not to go too metaphorical) I’m also looking at how bees work and applying it to this project. It’s not just one bee doing all the work, it’s a huge effort from various bees that have various jobs that come together for this common goal of survival, which is what we’re connecting as an overarching theme in this project—that if you help the bees and give them an environment you actually help the humans and help the environment, so on and so forth.

Sutton: I love that idea. Awesome. The strategic action plan seems like a huge step forward in being able to approach people and conversations about how to actually gain access to the site, whether that be an intermediate or more permanent plan. And I really like that you’re doing something off-site that’s actually directly related to the site, in close proximity; that you have this staging ground, per se, to start doing interventions, to start actually cultivating and curating happenings, events, gatherings, workshops and dialogues.

Chávez: Well, in one of the focus sessions at the Retreat, you were talking about brownfields and the challenges and how to address those. I found it really interesting how you were activating your site through different programs and events while you were also working on the nuts and bolts. You know, when it comes to writing grants or coming up with these programs, a lot of times you find yourself in front of the computer, and then it’s really easy to forget: I have this site, I have this site in public space! Can you just tell me a little bit about the different ways you’ve been activating your site during this duration?

Sutton: Well, we first signed a lease on the site in early 2008, and it was boarded up and basically condemned. The building was an operating gas station up until the mid-70s, when it went out of business due to the Arab oil embargo, and it turned into a florist for a little while and then a dry cleaners and then actually stored some trucks for, ironically, an environmental remediation company that would go around and take out underground storage tanks from people’s residences. That was a nonconforming use, and so the city evicted that business in 2002; we took control of it in 2008. So it had been sitting vacant for about ten years, and by Seattle regulations, anything that’s been vacant for more than five needs to be brought up to code, it needs to be seismically retrofitted, and so on and so on. So, we couldn’t really allow people to enter into the building because we couldn’t get an occupancy permit. And the building was in very poor repair.

So what we did at first is we painted the exterior of the building; we mowed down this mountain of blackberries and tried to clean up the site, and put up a new readerboard and lit the sign, and all of a sudden, after sitting derelict for so many years, there was this new visual life brought to it. It’s on a really busy road that connects two major neighborhoods in Seattle. It’s right next to Boeing Field, so we’ve got probably tens of thousands of workers driving by it every day. So, we made this visual impact, and we had these little slogans we put on the old readerboard, like: “Testing, testing, one, two, three!” when the EPA showed up to do some site work. It was a visual way to let the neighborhood, community and commuters know that something was happening at this site after so long; there was a sense of pride being instilled back into this little place. We started hosting a couple of community barbecues and events and got some different bands to play, and so it was all just a means of trying to get people to engage the site and talk about what was happening.

We were still in the very early development of our strategic plan. We kind of knew what we wanted to do, but we were still playing around with a lot of different designs and ways of going about that…and just learning about the site, doing environmental testing, and so on. So it was mostly community-based events. Then we started doing some panel discussions, got invited to a national brownfield conference in Tacoma and went and served on a panel for that. So we were talking about this little art project that was happening up in Seattle in front of a national audience. There were executives from Shell Oil and BP and Exxon as well as policymakers from the EPA and private consultants that work on those things. So that started growing the audience for the project.

Then we got to a certain point, after all of this research and all of these tests, where we sat down with the results with Ecology and starting talking: Alright, here’s what we found out; this is a worst case scenario, as far as contamination goes; it’s a little overwhelming to us because we’re just a group of artists trying to turn this into this public project; and what are you going to require from us? What are we going to need to do to clean this up, to let the public in? One of the first things that they wanted us to do was to limit access to the site because it is contaminated, even though it’s all below ground. They wanted us to fence the property off, and we understood, but that felt like it was negating some of our ultimate goals. But, to move forward with the remediation, we had to completely close the property off to public access.

We put up a construction fence, and we got four by eight panels and primed them, and we invited a bunch of artists in the neighborhood to create paintings. So now there’s artwork up around the fence, and we’re still doing stuff on the readerboard, and we’re in discussions with other artists to do some more installation-based works that happen behind the fence and continue to activate the space.

We’re probably looking at a couple of years of environmental remediation. The endgame for the project is still a ways out and we’ve got a big task of raising the funds and negotiating the bureaucracy to make that happen, but we’re committed to the site, even in it’s deteriorated state, as being a public asset—something that is continually changing, that’s visually appealing, that’s always increasing the stakeholders and the bigger picture. I do miss the music events and the barbecues and all of those things, but there’s not an ideal space anywhere around it to make that happen.

This was always meant to be a pilot project, a model for how to address other similar sites. We’ve talked about hosting temporary interventions at other gas station sites, not only in the King County/Seattle area, but when we travel somewhere else for a project. For example we’re going on a residency to MacDowell Colony and there’s a gas station out there, so we talked about having a one-night event at a site like that to engage a different community in how this idea might pertain to them. We’ve been thinking a lot about longevity and the story, and the “thing” itself is almost an aside at this point. The project, the art that we set out to make, has become more about the discovery and the process of learning and how to create something out of that. It’s changed our practice quite a bit, and we’re open to letting it influence what it wants us to do, which has been an interesting avenue to take.

Chávez: Yeah, I think, on that level, the Pruitt-Igoe Bee Sanctuary has totally transformed my practice. I mean, I’ve always been somewhat of a spacemaker, with the history of running an artist-run space to the nonprofit that I run right now, the Northside Workshop, where we actually saved this brick building from collapsing. But this is the first time where I’ve found myself kind of stepping outside of an actual structure, really talking about land and how building something may not always be the best option. I’m facing the challenge of the blank piece of paper, the vacant lot, and asking, how to you create a project that a community can connect with, and how can an individual also have a relationship with a site?

At the end of the day, when you work on these projects, they kind of weave in and out of artistic practice to learning a new language of a developer, or having to collect data of the economic impact of creative placemaking at a site this large or something like that. So, you kind of learn as you go. But you’re still an artist, you still act like this project is an art project. I think, when I came back from the Creative Capital Retreat, which I think was a very enlightening moment for me and the project, it they kind of took me out of the “art world” and placed me in “the world,” and now all of a sudden the world’s resources became my resources.

Sutton: I love that.

Chávez: Part of this project has been me going around and talking about it, splitting my time 50/50 in arts institutions or cultural centers and then in neighborhood meetings and stuff like that. I’ve engaged with other people and community groups, and I’ve talked to churches and stuff, but I had never thought before about developing a strategic action plan or learning about how corporations set up their structures or how developers get things done. And to be able to grab from those toolboxes to help me with this project—it’s like having a whole new set of toys I get to play with that are totally strengthening the project to go forward, to take it to the next level. In that way, the Retreat and the Creative Capital network are a total resource because—I forgot who said it at the Retreat—“artists create the roadmap for other people to follow.” And I feel like the network, that’s what it really has done for me. The things that we’re doing, they’re being done on different scales, wanting different outcomes, different desires, and we’re in this unique area that challenges or addresses cultural, historical, then environmental issues…and it forces the conversation to expand or shrink, or highlights a different part of the conversation, which is, I think, pretty exciting.

Sutton: I totally agree. In a way, I’ve had this love/hate relationship with this project in particular because of how much of an impact it’s had on my practice. I am, traditionally, a maker of things. I do a lot of work in the public sphere and I like to engage the community, but I generally like to engage through the things that I have made, not the process of making them. And this has changed that quite a bit, in that the process has become the project. Meeting with the Department of Planning and all those different agencies and funders and the lawyers—in every little step I’m not reinventing the wheel but I am having to learn how that wheel works. I’m learning how to be a bureaucrat.

I guess I’m an accidental environmentalist. We didn’t set out to address one particular problem; it was more about sites and how those could be reimagined. Learning about how things are remediated, how policy is dictated, through the process—this art project—has really made me want change or have an impact on the policy itself. So that idea of making something that is more about an experience and leaving something behind that isn’t just an object has been a really interesting avenue to pursue. The amount of time that spent on the computer and in the meetings and doing the planning—all that stuff is not particularly fun. I want to be in the studio, I want to be working with my hands, but it’s made every aspect of my practice stronger. And that’s, in large part, thanks to Creative Capital and that network, but also just being able to understand how my actions as an individual and a maker and a collaborator reach beyond my own personal practice. So it’s been fun and frustrating at the same time.

Chávez: Yeah, I mean, I think I have some of the same challenges… For me, it comes in cycles because the project started with me taking photographs and creating a film and creating a sculpture, and now most of my time is spent writing emails, trying to set up meetings, talking. So, where did the art go? Is it still there? But I think that’s just a healthy way of constantly evaluating what you’re doing—making sure that the art is always there and making sure that you’re thinking about this in an art way or that it’s going through some art filter. I feel like, as makers, essentially that’s how we experience information in the world and, especially for me, the pilot project almost had to be done. I had to physically make garden beds, I had to physically design the landscape that the bee sanctuary would go in because I had to fuel that need to make. Because then, once you make it and you see people interact with it, you can adjust and see where things need to be improved. It’s like going back to classic art school, you know, evaluating your audience or asking, how is your audience interacting with your work?

Sutton: One thing I’ve noticed is that when I’m making work outside of this project—the studio-based work and the installations—I take so much more pleasure in it, or I’m more aware of that than I used to be, because this project, with all of its different aspects, feels largely out of my control. I can do my best to shepherd it along and to try for this outcome, but ultimately I am just acting as an agent to try push this forward and to meet with the right people. It’s open to change and it has to be fluid. But the work that I make in the studio, I take a lot of pleasure in the fact that I can control every aspect of it, that nobody gets to see it until I’m ready for them to see it. That’s a much different thing, and I can escape the frustrations and the multiple layers of the Mini Mart project in the studio by focusing on one specific thing at a time, which is really nice. It’s made my practice and my ability to engage with people in the world all that much stronger.

Chávez: For me, it’s this really big project, but it has these strings of connection to the studio practice that’s really evolved how I think about art-making and how I approach the project itself. The interesting thing about Pruitt-Igoe is that I’ve been kind of engaged in this site, unofficially, for quite some time, just because when I ran my artist-run space I’d always get these emails from artists inquiring if they could come and do a residency in St. Louis because they wanted to do a project about Pruitt-Igoe, and my response was, “Oh, you know, it’s gone. There’s nothing to interact with.” And it was that amount of inquiry about the site, from the outside, that really highlighted the potential energy that this site does have. It’s a very interdisciplinary subject matter. Architects are really interested in it. Social workers are really into it. People who lived there, people who worked there—on so many different levels, people have a connection to what has been referred to as the worst example of public housing.

Pruitt-Igoe, when it imploded, was kind of marked as the death of Modernism. These very epic statements and the kind of horror, and attractiveness, of something so big being destroyed has really dominated the conversation about Pruitt-Igoe. That was the number one thing that really attracted me to the site—that there were multiple people interested in the site, and that they were all focused on the end of Pruitt-Igoe. So, it’s really important to me that this project continues the conversation surrounding Pruitt-Igoe, that the history books are still open, and that as a city, or as individuals, as groups, we can imagine different outcomes. We’re not stuck with a result. You’re able to control your future in some way by imagining this positive outcome.

Sutton: That’s great. Wow, well we’ve covered a lot of ground. I think we can wrap it up for now, and hope to continue the conversation as we both go forward on our projects. I feel very fortunate to have met you through the Creative Capital network! Please keep in touch and let’s keep thinking about how we might be able to share knowledge, use each other as resources, and glean from each other’s work.

Chávez: Likewise! It’s been a pleasure meeting you, and learning about your project. Let’s stay connected, and if you ever find yourself in St. Louis, my doors are always open!