Arts Writers Grantee Negar Azimi on "Bidoun" and the Iranian Avant-Garde

The Creative Capital | Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant Program is accepting applications through May 15. With a month left to apply, we’d like to share an in-depth look at one of the writers awarded a grant last year.

Negar Azimi, whose project The Shahbanou and the Iranian Avant-Garde won a 2012 Arts Writers grant in the book category, is senior editor of Bidoun, an award-winning publishing, curatorial, and educational initiative with a focus on the Middle East. Irreverent and conceptually adventurous, Bidoun magazine covers an eclectic array of art and culture: its latest, #28, features an interview with Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben about pets and animals, and a conversation with Larry Gagosian in which Azimi turns the art magnate’s attention away from the market to the Armenian diaspora of which he is an influential, but under-recognized part. In addition to her work with Bidoun, Azimi has written for Artforum, frieze, Harper’s, the Nation and the New York Times Magazine, among other publications. I asked her about what’s next for Bidoun and how the idea for her forthcoming book came about.

Kareem Estefan: Bidoun was founded in 2004 as a magazine focused on art and culture from the Middle East. Since then, it’s also functioned as a library, a curatorial initiative, and an educational space with arts writing workshops. Having expanded from a little-known publication to an internationally recognized hub for various critical and curatorial activities, can you reflect on Bidoun‘s mission and what’s next for you?

Negar Azimi: We’re approaching our tenth anniversary, so we’re currently thinking through where we’ve been and where we’re going. I think, in part, we hope to become an incubator for all sorts of projects. You’ve probably noticed that our version of the Middle East includes Los Angeles, Detroit, New Delhi…we’d like to carry this forward by nurturing projects with partners who, like us, think expansively about culture, whether they’re our own fantastic contributing editors or people from outside of our immediate network.

It’s an exciting moment. We’re preparing an exhibition about Reza Abdoh, an Iranian-American avant-garde theater director who died of AIDS in the 1990s, for Artists Space. We’re also staging sort of the apotheosis of the Bidoun library for the 2013 Carnegie International. And we are in the final phases of translating Bidoun # 25, which was made in Egypt, to Arabic and thinking about launch events around that. We’re also going to launch a new web site, which is still in its planning phases.

Kareem: You’ve framed Bidoun not geographically, but rather in terms of an ethic or style, or perhaps through approaches and concepts one could link to the word “Bidoun,” which means “without” in both Arabic and Farsi. Could you expand on the limits of a geographical framework when discussing art and culture?

Negar: The birth of Bidoun coincided with a post-9/11 period when there was a rise in the visibility of the Middle East in general and, in the arts, a rise in the visibility of art scenes in places like Cairo, Tehran and Beirut. Early on we realized that, as a small team, we couldn’t possibly represent all that was happening culturally across the Middle East—nor did we want to. Our version of the Middle East is very partial, and pretty much tied to cities with which we as editors and individuals have relationships. And again, even within this region, these are very different places with very different histories … so the totalizing tendency never interested us. I’d like to think we played a very small role in pushing back against the generalizations.

Kareem: How did your book about Iran’s arts scene in the 1960s and 1970s, as shaped by the Empress Farah Diba, begin? Can you describe its focus in greater detail?

Negar: The project came about in part through an extraordinarily long interview my colleague Babak Radboy and I did with Tony Shafrazi, for Issue #18 of Bidoun. It was conducted over several days at his Chelsea gallery, and he talked very openly for many, many hours—it was like a tsunami of incredible words. It turns out that sometime in the 1970s, after he had defaced Picasso’s Guernica at MoMA, Tony returned to Iran, where he was born, to be a part of the cultural scene there. From there we started talking about what was happening in terms of the arts, which was fascinating, as a very old civilization suddenly had access to vast resources care of the oil in the ground. And there was a desire to invest in culture, a desire that for the most part came from the Empress.

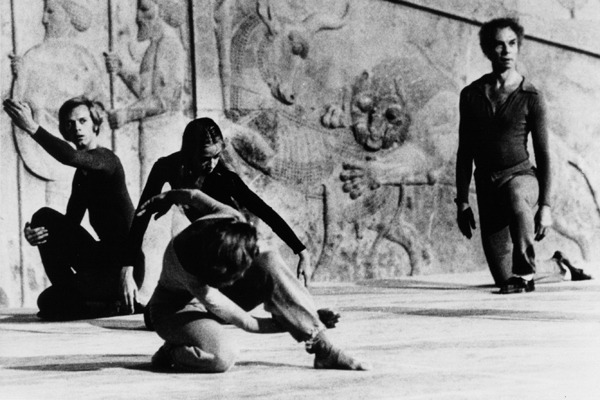

First Ladies are very often patrons of the arts in some way, you know, cutting ribbons at openings or buying two or three oil paintings here or there, but Farah Diba was implicated in a much more profound way. I started doing more research about the museum of contemporary art that opened in 1977, as well as the Shiraz Arts Festival, which took place over 11 years in the desert, and then eventually interviewed people like Bob Wilson who took part in it. He, for example, produced one of his most ambitious, completely idiosyncratic operas at the festival, called KA MOUNTAINAND GUARDenia TERRACE. And from there one thing led to another. The Empress became a pivot for the book; everything comes together around her.

In a sense, the project represents an intersection of two worlds that I care about deeply: Iran, where my parents are from, and then you could say the global avant-garde of the 1960s and 70s. At the same time, it’s inevitably a fascinating political story as investing in the arts was one piece of Iran’s ambitious modernization program.

Kareem: Could you see any relevance today?

Negar: Sure. It’s a familiar story. Take the Emirates or Qatar today as they use their wealth to invest in the arts.

Kareem: Is that something that your book will reflect on? Do you compare the Shiraz Arts Festival to today’s biennials situated in the Middle East, or more broadly, the Global South?

Negar: The project won’t really go beyond the 1970s, I don’t think, but I hope it leaves readers with something to reflect on vis a vis resonance with the present moment. It’s really more about revisiting a history that few people know about—or thinking about the 1970s in a whole new way. In the glut of information about the Iranian Revolution and the Shah, there’s very little scholarly or even popular work on this cultural moment. It tends to be overlooked. So at the most fundamental level, it seemed important to document it, while the people involved are still alive.

Kareem: You mentioned oral history, and I know you’ve also expressed interest in emphasizing instability by weaving your personal voice as well as found texts into this account. What attracts you to this hybrid, less settled form?

Negar: At the very beginning, I thought this project might completely take the form of oral history, in the tradition of George Plimpton and Jean Stein’s Edie. My co-editor Mike Vazquez gave me a copy of Edie a really long time ago—I’m totally grateful to him for that—and from then the idea stuck. The characters in the Iranian story are amazing, colorful, even cinematic. In terms of the instability you mention, like any moment in history, everyone’s account is partial, so you find that there are often contradictions and inconsistencies and aberrations of all kinds about who did what and when and so on. I quickly realized that this was part of what made this moment so interesting to me. I guess I hope to be faithful to that in the form of the text—though it might be too early to tell how it will all play out.

Negar Azimi received a 2012 Arts Writers Grant for her forthcoming book The Shahbanou and the Iranian Avant-Garde. The Arts Writers Grant Program is accepting applications for its 2013 grants through May 15. Read the guidelines and apply online at www.artswriters.org.