Shadow Play Reinvented for Digital Media Explores Urbanization in China

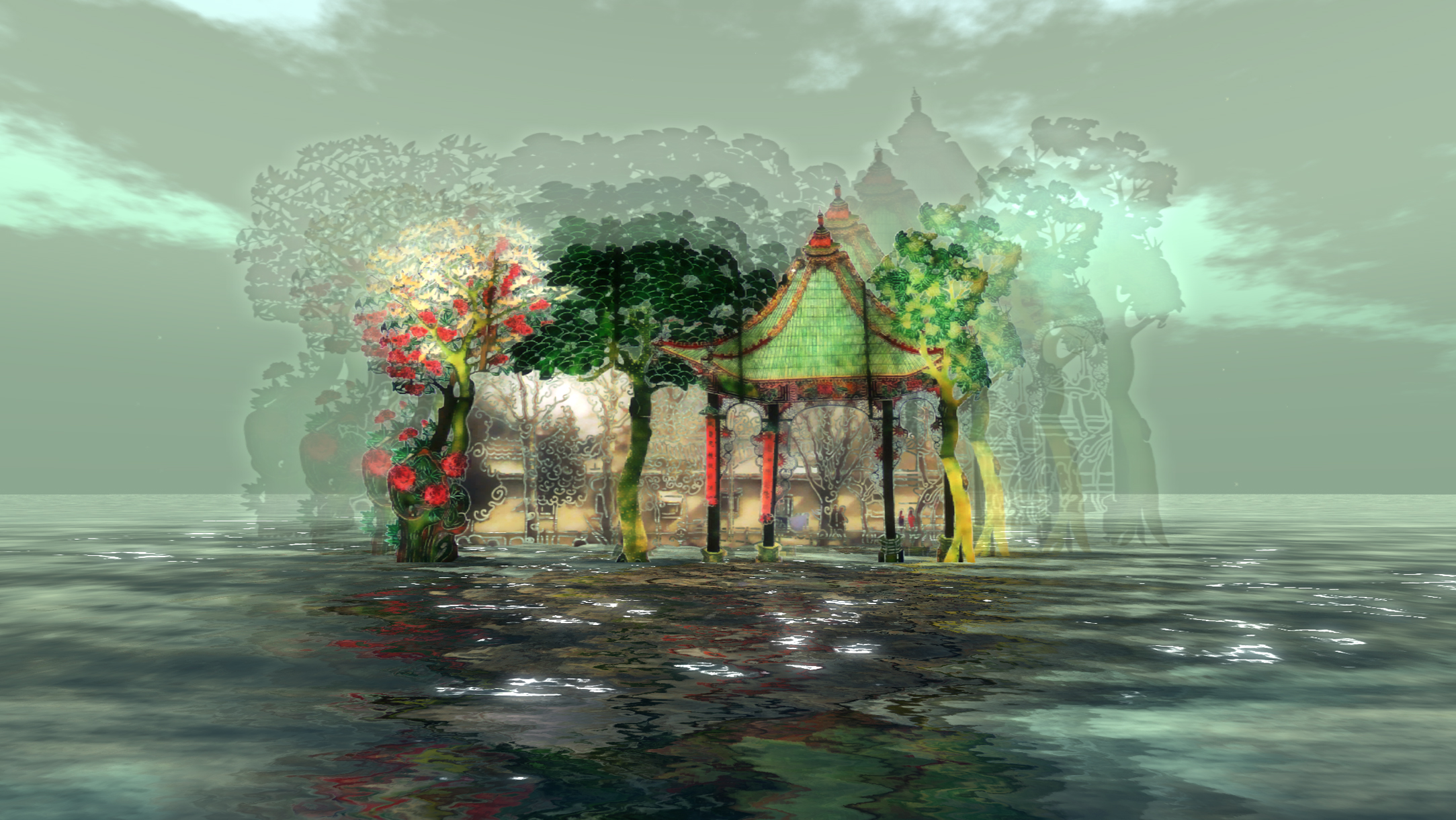

Virtual reality screen still from Shadow Play: Tales of Urbanization in China by Lily & Honglei, 2020.

Since 2013, China has experienced a dramatic transformation due to the agrarian population moving to cities. The artistic collaboration, Lily & Honglei explore how families in China have been torn up by this rapid development with little concern for their well-being in their Creative Capital Project Shadow Play: Tales of Urbanization in China. Experimenting with new media technologies, Lily & Honglei have based the aesthetics of their project on shadow play, a folk art style favored for its accessibility by the very Chinese farmers and laborers at the heart of their story. The project premieres at the Museum San Salvatore in Lauro, Rome on October 20, 2020, but can also be experienced through videos and images on the artists’ website, as well as within the virtual reality network, Second Life.

Lily & Honglei spoke to us about the transformation they have witnessed in China and the history of shadow play.

Alex—Can you describe the project, and how you started working on it?

Lily & Honglei—Shadow Play is a project that allows us to explore new relationships between artistic form and narrative, as well as traditional media and digital technology. Meanwhile, our living in China for three decades has provided the foundation for the project research that investigates the historic transformation from agrarian to urban society, or, the industrialization process unfolding at warp speed.

Since the early 1990s, we have witnessed rapid changes in the world’s most populous country that has been essentially agrarian throughout its millennial history. But the most drastic transformation didn’t begin until 2013, when the country’s leadership unveiled its plan to integrate 70% of its population into cities. It really made us wonder how the physical and cultural landscape in both rural and urban areas would be altered, and how people’s everyday lives would be impacted. So we formally started the project in 2014. It’s been a tremendous challenge for visual artists to cover various aspects of the urbanization systemically while telling people’s real stories compellingly.

Based on our experiments in new media and a long-term passion in folk art traditions, we decided to utilize virtual reality and augmented reality platforms that could effectively integrate realistic imagery with Chinese shadow play motifs for storytelling.

Alex—Tell me about the history of shadow play as a medium, and why you decided to use this format to tell the story of urbanization in China?

Lily & Honglei—Shadow play, or shadow puppetry, likely originated in China over two thousand years ago during the Han Dynasty. It became a people’s art form because of its portability, and simplicity. Night-time performances were perfectly suited for the working classes. Farmers and laborers engaged in puppeteering, singing, musical instruments and storytelling after the sun went down, which created a tradition that became the heart of their communities. It became one of the most wide-spread folk arts that survived everything from war and famine, to the regime changes and the Cultural Revolution.

Sadly, it has been on a steep decline as a result of modernization of entertainment, as well as urbanization, which reminds us of the crisis that many cultural traditions have been experiencing in the 21st century. In this context, shadow play offers a perfect visual format for delivering stories about the rural population transitioning to urban migrant workers, which is the main focus of the project.

Alex—I’m curious if you can help paint a picture for people who do not know, by selecting one or two of the stories from your work, of what it really is like to experience this move from agrarian to urban society in China?

Lily & Honglei—The project unveils tragic stories of a rural family. While the characters are fictional, the stories are in fact based on real incidents. In Chapter I, the village chief leads a peaceful life with his wife and son in the countryside until one day a demolition team arrives, threatening to take over the land and tear down houses for the purpose of urban development. Consequently, the chief and villagers set up barricades around their homes to prevent the improper demolitions. On a rainy morning, some villagers witness four men in black uniforms following the village chief, holding him onto the ground and running him over with a construction truck. The beloved chief is killed brutally during a land dispute—the type of violence experienced by too many people in rural China.

Is there any hope for the individuals and families falling into destitution as a result of society’s relentless transformation? Perhaps only if people choose not to ignore these tragedies.

In Chapter III and Chapter IV, the main character, the wife of the late chief, moves to a city after her home is demolished and her son goes missing. In order to survive as well as searching for the kidnapped boy, the courageous mother takes on an incessant journey in the city where she observes breathtaking constructions and destructions. She stays with a friend’s family dwelling in the “underground city,” a gigantic structure we created based on the reality that millions of migrant workers live in Beijing’s underground spaces with substandard conditions in order to reduce housing expenses and time traveling to work. She also observes that her friend’s family and other migrant workers cannot afford medical treatments for their children in the city; in despair, some of them abandon their babies in front of the hospital.

As she goes on joining other parents searching for their missing children, a scene of complete devastation unfolds—five young boys are found dead of carbon dioxide poisoning in a dumpster where they take shelter on the chilly night. They are among the countless so-called “left-behind kids” who live in the countryside by themselves at a very young age while their parents have to move to the city for jobs. These real stories signify that the turbulent social change has relentlessly torn apart the social fabric, especially the family structures.

Alex—These stories are heartbreaking, but needed. Is there any part of the story that is hopeful?

Lily & Honglei—Many of us perceive the urbanization process in developing countries, including China as an inevitable step through which more people may elevate their living standard and obtain more opportunities at an individual level. For a country as a whole, urbanization, driven by the invisible force pursuing higher productivity and leading towards a consumerist society, is seemingly unstoppable. In this context, our work isn’t intended to deny the significance of urbanization, but instead questions how people, environment, and cultural traditions are positioned during this process.

By shedding light on tragic, real human stories, Shadow Play aims to remind us that urbanization should go beyond economic advancement as a sole consideration. It is an open-ended story in which the protagonist will never stop searching in a city depicted as a maze without exit. Is there any hope for the individuals and families falling into destitution as a result of society’s relentless transformation? Perhaps only if people choose not to ignore these tragedies.

Alex—Can you talk about the show in Rome? Is there something that is online that people around the world will be able to view or engage with?

Lily & Honglei—Since the project’s completion, we have been looking for an ideal venue that may present Shadow Play in a comprehensive way. Because the work involves different digital platforms, presenting the project might pose some technical challenges for the venue and the curators alike. Meanwhile the project’s subject matter may require understanding somehow rooted in lived experience.

A solution was finally reached when a curator of the Museum of Contemporary and Digital Art in Italy contacted us for an exhibition that will be held at Museum San Salvatore in Lauro, Rome. In a place recalling high Renaissance glory, the large-scale event showcases new media art projects produced by artists around the globe, including some very influential ones. Shadow Play will be presented comprehensively as videos, prints, augmented reality, virtual reality and paintings. Entitled “Renaissance 2020,” the exhibition sets up a perfect stage for our project that integrates new media with traditional visual forms.

One thing a bit special about Shadow Play is that its digital nature allows the presentation to be delivered in high quality via the internet. In fact, we plan to launch the project online as part of the upcoming premiere. The project website serves as an all-in-one platform through which the audience may access not only over a hundred images and video clips as documentation of the project, but also live interfaces of the virtual installation and augmented reality sections.

For example, on the webpage, there will be a link to Second Life virtual world where the audience can explore our project in cyberspace on and after the day of the project premiere. Following viewing instructions on the webpage, the augmented reality work can be experienced using a smartphone. We hope these interactive components will enhance the audience experience. Meanwhile, they also demonstrate our perception that online presentation may play a more and more significant role for exhibiting visual arts in today’s world.

Alex—Tell me more about the Second Life component. In this time of the pandemic, I wonder if it could be an interesting model for other artists to use?

Lily & Honglei—Second Life is similar to an online video game platform, but with no set objective. Users may create their own environment for different purposes including education, arts, entertainment etc. We began experimenting with building virtual installations in Second Life back in 2007, when the platform gained global popularity among individuals and institutions alike. The program’s ability to construct elaborate structures with meticulous textures convinced many visual artists and designers to sign up. In fact, we came in contact with quite a few highly respected media artists through Second Life and began fruitful collaborations on numerous exhibitions.

Since then, we have produced several projects involving the virtual world due to two major reasons: first, it serves us well as an efficient design software by integrating 2D images with a 3D environment to generate unique visual outcomes; second, as an online multi-user platform, it has the strength in delivering presentations to a worldwide audience and allows them to interact with the artworks and artists in real time—this nature has motivated us to launch the premiere in the midst of the pandemic.

It’s not hard to imagine that the virtual world has seen a surge of users since the pandemic lockdowns—an increase of 60% new visitors was reported in April 2020. And surely it would be great fun if more artists join us here, either for virtual exhibitions, live performances, or simply building an artist community in a place that transcends geographical distance and physical barriers.

Alex—You received the Creative Capital Award in 2015. How has Creative Capital been helpful to your project?

Lily & Honglei—The help to our project we received from the Creative Capital Award is immeasurable. Besides the obvious tremendous financial support, Creative Capital helps us to better organize our timelines of research and production. For instance, in 2016, with the funding support, we were able to attend an immersive technology conference in Toronto, which greatly inspired us to utilize new digital imaging applications during the early stage of the project.

Creative Capital also sets up a framework that assists us to achieve the completion of a very challenging project—under Creative Capital’s advice and requirement for funding, we reflected on the project progress periodically and were therefore able to take concrete steps towards the materialization of a relatively complex plan.

Creative Capital is also extremely helpful with making recommendations—our advisor reached out to another local art organization in order to help us receive more support at a local level. Last but not least, the community at Creative Capital, especially our small “cohort” consisting of nine very talented artists, has been a great inspiration for us throughout these years and always will be in the future.

All in all, during the long project production process, Creative Capital has been not only the most significant financial support, but also the moral support through recognition, organizational connections, and building artist communities.

Read more about Shadow Play: Tales of Urbanization in China by Lily & Honglei on their project website.