Alternative Models for Artist Sustainability in a COVID Economy and Beyond

Overlord of the Auntie Sewing Squad at her Hello Kitty Sewing Machine, self-portrait of Kristina Wong, 2020.

When the pandemic forced the closure of galleries, museums, and cultural venues, many artists were left with canceled contracts and no prospect of income for the foreseeable future. This sudden shift prompted many to reconsider their relationships with institutions that supposedly shared their same interests. In Creative Capital’s recent online conversation on the impact of the pandemic on the creative economy, Amy Smith moderated a discussion between Daniel Park, Caroline Woolard, and Kristina Wong. All four are thinking about other ways of working in solidarity and community, and maintaining financial stability and wellness as artists.

Artists find themselves among the many other precarious careers in the US. Predominantly freelancers, often underemployed, artists don’t receive many of the benefits that many full-time employees count on—a fact that was made painfully clear during the economic shutdown. “We are basically living in a failed state right now,” Smith, a Creative Capital Awardee, artist and financial advisor, explained, remarking on conversations she has had “almost every day with an artist who is either trying to get an SBA loan, or grant, or retain unemployment, or get on it for the first time.” The “safety nets” that are ostensibly set up to help people make it through moments of crisis are not working. Artists are left to rethink how they benefit from their work, and in doing so, lead creative thinking around what kinds of new models can carry us all out of the pandemic and beyond.

Sewing Squads, and Resisting the “Failed State” of 501c3s

The new urgency and instability of the economic shutdown has forced more wide-spread reflection on what kind of work artists make, how they gain a livelihood from it, and specifically how they can work in solidarity with their community, rather than in competition with it. Wong, another Creative Capital Awardee, and comedian artist based in Los Angeles, pivoted her live-theater practice to organize what she called an “auntie squad.” Together they have sewed over 60,000 protective face masks for frontline workers, operating largely outside the system of capital, or monetary exchange. Wong and the sewing group have been profiled on USA Today, Time Magazine, Good Morning America, and Washington Post, building a new audience and community. Despite the group’s success, she has resisted encouragement to turn it into a nonprofit, or 501c3. “It’s meant to be a stop-gap measure,” she said, but beyond that Wong finds the 501c3 model problematic.

Artists like Wong often keep nonprofits at an arm’s distance by using fiscal sponsorship to support their work. “For organizations of color, a 501c3 doesn’t make sense” because of massive overhead costs, and the need for a wealthy donor base and board of directors. In Wong’s experience, boards for organizations of color can help fundraise, but the access to capital isn’t comparable to predominantly white organizations.

Furthermore, nonprofits and arts organizations tend to suppress financial literacy through a lack of transparency. Cultural workers rarely learn to read financial books by their employers. As a result, discussing finances openly is avoided in the cultural landscape. For artists, in addition to diversity and inclusion, equitable power can come from more financial literacy, the artists in the discussion agreed: open bookkeeping practices, training cultural workers to read profit and loss statements, and making budgets something safe to talk about in the art world.

So, has the nonprofit model failed artists, especially artists of color? Park said that it is working as intended. The nonprofit structure was created and enforced by the government in the 1960s and ’70s, he explained, “in order to regulate the activism that was happening at the time, so that these organizers doing radical work became dependent on particular tax structures, the government, and the wealthy.” Boards of nonprofits are generally not allowed to receive income from the organization that they are governing. That means the fate of the organization, paradoxically, is bound to people who aren’t as tied to it as its workers. That’s why most boards are giving boards, effectively ensuring that “there is no oversight or accountability system to oversee the actions of a board.”

“All of these different forms of oppression that we’re dealing with are deeply interconnected to how we create our art, and what’s going on in the world.” — Daniel Park

Resist, Occupy, and Create

Many artists feel like they either have to benefit from their art practice within a capitalist system at the expense of others, or choose to opt out completely. This either/or dichotomy puts artists at a disadvantage, argued Park, a Philadelphia-based performance artist who also works for the U.S. Federation of Worker Cooperatives whose mission is to build a thriving cooperative movement of stable, empowering jobs through worker-ownership. By turning their backs completely on the capitalist system, “artists have given up their power and the recognition that they are actually labor and integral to these systems.”

Instead of refusing outright to be a part of capitalist systems, Woolard, a visual artist, educator and arts organizer, is inspired by the motto of the Zapatistas: “resist, support or occupy, and create.” While she resists racist and oppressive structures, she also occupies a tenure-track academic position. The university system, she said, while certainly problematic, is also “the largest patron for living artists that the world will ever see.” This “patronage” has allowed her to research, develop, and create an art school of the future. Woolard pointed out that seven out of the 10 most expensive schools in the country are art schools, and the pandemic has furthered a collapse of this system. Woolard has used her privileged position to “reconsider what learning we want in the arts, and who should be accessing that kind of educational system anyway.”

Benefit Societies, Barter Systems, Community Land Trusts, and Worker Coops

The artists mentioned a number of alternative models that operate within capitalist structures, yet in opposition to them, like benefit societies, or mutual aid network, barter systems, and worker coops. These efforts to promote well-being through solidarity and community are concepts pioneered and developed largely by Indigenous communities and people of color, but are not often lifted up in the same way as the white-led initiatives or businesses inspired by them.

One of the first Black mutual aid organizations of its kind, the Free African Society was a pioneering form of the mutual aid network that developed in the 18th century. The network was set up to counteract the second-class experience of Black people in Philadelphia in terms of health care, employment, and education. Founded by two former slaves, Absalom Jones and Richard Allen, the society asked members to pay a “shilling of silver” a month to benefit others in their community. They played a huge role when a Yellow Fever outbreak affected the city in 1793, even outside of their immediate community and member base, by taking care of people and burying the dead. The society supported a community that was ignored by the government, and it has given us “models for things we take for granted today, like insurance companies and co-working spaces,” said Smith.

Woolard has used barter systems as the basis for some of her art work, like her project Trade School, that set up a self-organized learning community that ran on barter where anyone could offer to teach a skill, and learners offered barter items to meet the teacher’s needs. During the time it was operational (2009-2019), the Trade School served over 22,000 people through self-led classes. With the help of other artist organizers, Woolard established classes all over the world wrote a manual based on the experience to help others who want to work with a barter system to establish a learning space, or fill needs of their community.

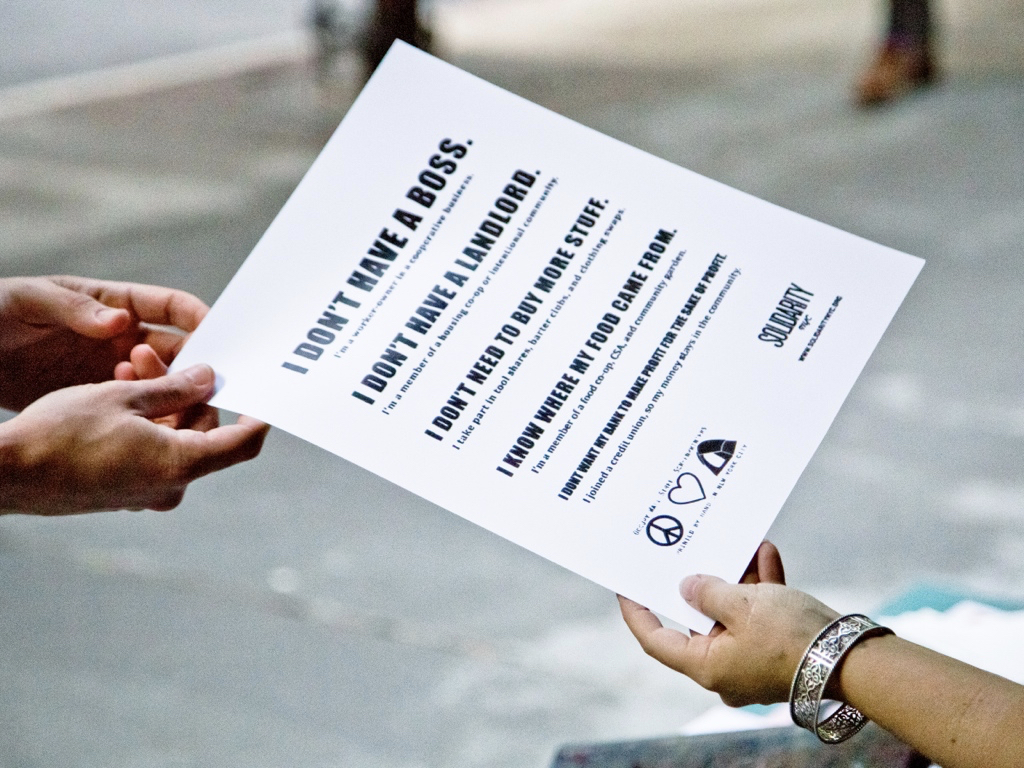

I Don’t Have A Boss by Caroline Woolard for SolidarityNYC, typeset by Andrew Persoff, printed by Patrick Rowe at Exchange Café, 2013.

The Community Land Trust (or CLT) is another system that Woolard finds inspirational. In the 1960s, civil rights organizers recognized that denying property rights to people of color effectively maintained white supremacy in the US. Originally, CLTs were developed to help Black farmers benefit from the labor on their own farmland, but they have since targeted housing crises, especially among communities of color. These community-run, nonprofit landholding organizations help low-income buyers obtain homes, allowing group ownership of the land with individual ownership of houses. More than 200 CLTs exist in the US, and cities like New York and Houston have set forth tax regulation plans to encourage more of this type of development.

The pandemic has made it apparent to more artists than ever before, Park said, that housing justice, health justice, and hunger justice are all artist issues. “All of these different forms of oppression that we’re dealing with are deeply interconnected to how we create our art, and what’s going on in the world, and we can’t separate ourselves from that.” With this in mind, the US Federation of Worker Cooperatives, Park explained, is getting ready to debut a new cooperative initiative called Guilded. Freelancers will pay a small membership fee to join, making each member, essentially, a partial owner of the business. This new initiative is designed to fill in some of the gaps “that the government should be providing, or the clients that we’re working with that should be providing the upfront costs.” For instance, Guilded will provide the administrative support for artists’ gigs, taking care of essential needs such as access to affordable health insurance and payment management. The member-based structure allows artists to be a part of the decision making process, but because they can also employ administrators, some of the hard work can be taken off their shoulders.

Looking Beyond the Pandemic

Rather than downplay or ignore the problems at the heart of the legacy organizations and nonprofits, institutions should acknowledge them through transparency, allowing artists the ability to consent to be a part of their work. The artists felt that this moment of turbulence, uncertainty, and failure of our systems as a time to build awareness of alternative models out of the sheer need that the pandemic is causing from day to day. “My hope,” Woolard said “is that more and more artists, as they are engaging in mutual aid, gift giving, and barter systems, realize that that is connected to worker ownership, and worker dignity. There is a respect to people around me that I’m sharing resources with, and I can be cared about as an actual human.”

Listen to the full conversation between artists Amy Smith, Daniel Park, Caroline Woolard, and Kristina Wong.