The Financial Heart and Soul of an Arts Nonprofit: Leslie Singer on 20 Years at Creative Capital

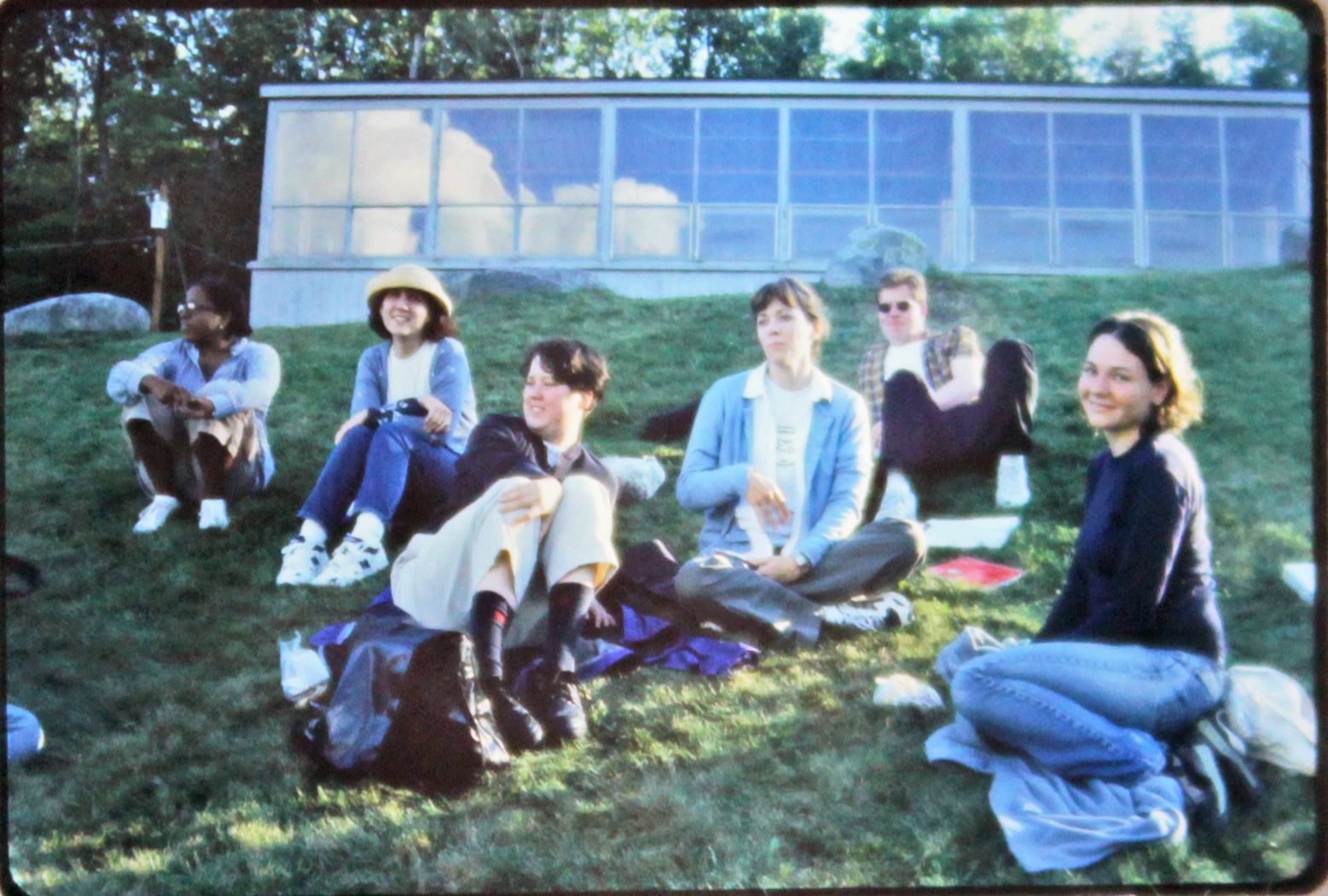

Leslie Singer, third from left, sits with artists and coworkers at the first Artist Retreat in 2000.

In 1999, Ruby Lerner, the Founding Director of Creative Capital, hired Leslie Singer as the first employee. Singer has been with Creative Capital since then serving as COO, and now serves as Interim Executive Director. In her 20-year history with Creative Capital, Singer has not just seen how the organization has grown, but has also borne witness to the changing landscape of the arts and the nonprofit world.

It may seem normal today, but Creative Capital was founded on the unusual idea that an organization should give money directly to individual artists. That premise “seemed like a brand new, shocking thing at the time to do,” explained Singer. In the 1990s, the National Endowment for the Arts stopped giving directly to artists after some of the artists it funded became the subject of political controversy leaving many in the art world worried about its effect on the artistic profession. Creative Capital was formed to operate from a place of trust when it came to artists; giving to the artists directly, unafraid of powerful and possibly controversial work.

Singer is an artist herself, and expected to go to art school in the late ’80s and early ’90s, when she was experimenting with film technology and music. Her work was a raw reaction to the politics of the time, “Iran-Contra, anti-Reagan sentiment, and the AIDS epidemic.” In the mid-90s, Singer went to work with Lerner at Association of Independent Video and Filmmakers as a bookkeeper, then moved to Creative Capital when Lerner became its founding director. Singer saw Creative Capital as “not your grandfather’s foundation.”

Speaking about the early days of the Creative Capital, Singer certainly captured the fun and heady time when they supported the first year of artists, some of whom were already well-known in the art world. Singer recalled meeting artists like Xenobia Bailey, Barbara Hammer, Elisabeth Streb, and the young Sandi DuBowski after the first award cycle. For Singer, “these were people who were really legends and to actually meet them, that was a big deal.” Singer said that despite their stature and accomplishments, they all retained a sense of humility, which was inspiring to her.

I talked to awardees who have said the money we give them is keeping their families going… That’s something that is very precious. It has to be treasured.

Early on, the Creative Capital team realized that there would be no “cookie-cutter” or “one-size-fits-all” way to meaningfully support artists. In working with artists on financial planning and time management, “you set out on a journey with an artist, and it can be personal and tricky. From day one, we’ve all tried to be as respectful as possible.” Working with individual artists so intimately, and bringing them all together to learn from each other, presented challenges, especially without the technology that we take for granted today. Describing the last day of the very first open application, Singer recounts artists walking into the downtown Manhattan office on a hot day in August 1999, and filling out the applications by hand. Referring to the work samples section of the application, Singer said, “it was the day of the slide carousels. We had to go over to East Village where Spectra Photo used to be. I walked there from our office with garbage bags full of slide carousels.”

The vision for Creative Capital was that it would be a place that understood artists and employed them—it would be responsive to artists’ unique needs. It was initially set up as a five year experiment, and Singer explained, “there was a lot of drama as we were trying to find our footing. We were all crammed together, sharing a little tiny office with the Warhol Foundation.” Singer described having to share a computer with other coworkers, and that everything was done over the phone. When asked about the first Artist Retreat at Skowhegan, she laughed, listing the unforeseen challenges they faced: it was freezing, even though it was August, and it rained. “It was kind of like Woodstock,” she said.

Today, Creative Capital has come a long way from those early, trial-and-error moments. When Suzy Delvalle came on as Executive Director in 2016, she often called on Singer to explain the reasoning and history behind how Creative Capital functioned. “There was always a backstory to everything,” Singer reflected. “It’s like a soap opera.” Using Singer’s institutional memory as a starting point, Delvalle and the staff evaluated and codified a lot of the processes of supporting artists. Singer reflected on how these updates have helped improved Creative Capital’s work: “we’re better at getting out of our own way. We don’t overthink the process any more, and because of technology, we’re allowed to be more responsive, but in a more balanced way.”

Recently, the pandemic has demonstrated how Creative Capital was designed to respond to artists’ needs. “I talked to awardees who have said the money we give them is keeping their families going. I’m always amazed at the goodwill and gratitude. That’s something that is very precious. It has to be treasured.”

Asked if she was worried when Lerner had stepped down as Founding Director in 2016, Singer reflected on what Creative Capital has become: “It’s its own entity. Ruby built something bigger than us. We all did something bigger than us that’s going to live on.” After 20 years at Creative Capital, Singer pointed to the people as the key reason why she has stayed on for so long. “The people I work with, the awardees, the funders, the people in the field. That’s what keeps me going. You always wake up thinking, ‘Oh lord, what is it going to be today?’ But wonderful things happen too, every day it’s something new.”

Once, a colleague pointed to a stack of checks in Singer’s office, funding requests made by awardees to continue their work on their projects. They stated that the checks symbolize the people Creative Capital supports: “Every week these checks are going out. All of these are people who are counting on you.”