Mariam Ghani Breathes New Life into Five Unfinished Films from the Afghan Communist Period

When the Communist party took over Afghanistan after a coup d’état in 1978, Afghan Communist leaders understood that art and film could be used as a tool, or even a weapon. Mariam Ghani’s new documentary, her Creative Capital Project, What We Left Unfinished, looks at the history of the Communist era between 1978 and 1991 through the stories of filmmakers working at the time. Ghani focuses on five unfinished films that both capture the turbulent events and emotions of the time, and also demonstrate the power and potential of these films beyond their propaganda value. What We Left Unfinished screened at the Berlinale in February, and premieres at the San Francisco International Film Festival, April 11-16, 2019.

We spoke to Ghani to learn more about the film.

Alex Teplitzky—How do you describe this project?

Mariam Ghani—What We Left Unfinished is a feature-length documentary about five unfinished films from the Communist era in Afghanistan. I like to describe it as a “mostly true story” because it is, of course, made with the footage from those five unfinished fiction films, as well as the behind-the-scenes stories of a tight-knit group of people who went to extraordinary lengths to keep making films at a time when films were considered by the government to be weapons. That led to the filmmakers becoming targets for attacks by opponents of the government.

The dreams and nightmares of the rapidly changing regimes of this time also started to merge with the stories that were told onscreen. I like to think of these films as the fever dreams of Afghan communism. I think you can see in them both some of the truths and some of the most important fictions of the time.

Alex—The part that really spoke to me is that, almost immediately, the power of art and film is recognized by the government. You said it’s seen as a weapon, but films were also used as a tool. The difference between that and how the US government now views art was jarring to me. What was the sense that you got of the role that film could play and did play, and how did it change?

Mariam—There are two currents that run through the film. One looks at how the governments of the time used film and thought about film, and the other looks at how the filmmakers of the time thought about their films and wanted them to survive into the future. The governments obviously wanted to deploy them politically, and had specific ideas about how to do that. A lot of those ideas were shaped by the Soviet conception of all films having propaganda value. Even a fiction film that’s a love story or family melodrama should also have some propaganda value.

“These filmmakers sincerely believed that film could save Afghanistan from itself, and they still believe that today.”

On the other hand, the filmmakers of the time would describe their own films as having other purposes beyond propaganda. I think some of them were trying to embed subversive messages into their films. They wanted to use their art as a means of subtle resistance, because if you resisted openly, you would end up in jail or dead. Others were trying to create a record of the time that would preserve for history some sense of what it had been like to be Afghan and to have lived through that period. And others were engaged in this interesting project of not so much recording what was actually happening, as projecting onto the screen an idealized image of what they wished was happening, and really trying to create through film a secular culture, a meeting point for people who wanted to live in a secular Afghanistan that didn’t exist yet.

This is one of the most important takeaways for me from the film, because it’s a project that is still ongoing and unfinished in Afghanistan: the project of creating some kind of meeting place in art and culture that crosses ethnic divisions, political divisions, religious divisions, all of these differences that function as fault lines in Afghan society and are still tearing us apart today. The idea of using film and art as a way to bind the country together, as a way to create a space that is not marked by any of those differences and can be shared by everybody because it exists outside of all those markers is a really valuable one, and still really important. These filmmakers sincerely believed that film could save Afghanistan from itself, and they still believe that today.

Alex—It was refreshing to me to hear the filmmakers talk about their work in the same way that we expect the boldest artists to talk about their work today. Watching the film, I wondered what it was like for you while these films were being made? What’s your personal connection to this story?

Mariam—My family’s story during the Communist period is very different than what these filmmakers experienced, since they were in favor with the Communist regimes, and my family very much was not. It was not an obvious thing for me to take on this subject or investigate this period through this particular lens, because my film doesn’t present the usual story of this time. This is the experience of a fairly narrow slice of the Afghan population, but I think it’s an interesting and different way to enter into this history.

My family’s experience is the opposite. Every male member of my father’s family who was still in Afghanistan in 1978 was imprisoned by the Communist party after the coup d’état of ‘78. Some of them were released during the amnesty of ‘79, but some of them were not. My grandfather was actually in prison for ten years. So there’s a lot of intense backstory and very deep feeling in my family about the Communists. One of my great-uncles was actually executed in ‘78, and some of my other great-uncles were tortured in prison.

There’s a story in our family about one of my great-uncles, who walked out of the central prison in Kabul after the amnesty in ‘79, and saw his own name on the list of dead that was posted on the prison gates every week. He escaped by the skin of his teeth. So it’s complicated for me to talk about Communist Afghanistan. With this film, I deliberately tried to avoid presenting a straightforward history of the Communist period. For every Afghan I know, there’s a different history of that decade—a different and very personal take on the story.

During and after a civil war, history tends to splinter because everything we knew about ourselves is shattered. I don’t think we’re yet at the point in Afghanistan where we have reassembled those pieces into any kind of coherent whole with respect to the Communist period. In making a film that looks at that time, even if through film, I wanted to be careful to insist on the gaps and contradictions in the stories that were being told. Not to present the history in a way that presumed it was complete, or that it was the only way this story could be told.

Alex—I’ve heard you talk about the film for a while, and in the meantime I’ve seen some of your other work. For instance, The City and The City, and I recently saw Dis-ease at the Museum of the City. Both films have this artful method of presenting nonfiction material, so I was curious how you would present this film. How did you decide to approach it as more of a straightforward documentary rather than a video art piece or something like that?

Mariam—Well, as you mentioned I’ve been working with the material in What We Left Unfinished for quite a long time—about six years now. I did a number of things with it in the art world in the early years of the research. I made exhibitions out of the research materials, I did live cinema events with the silent rush prints where we activated them in different ways, I organized panel discussions in different parts of the world to try and think through them with different people, and I did all the normal things that I do as an artist with material like this.

Then I reached a point where I felt like the material wanted to be a film. This made sense, since it’s filmic material. I felt like making a feature was the best way to pay tribute to what these filmmakers had originally intended to do with their footage. I will say that my first idea was to make a fiction film out of the unfinished fiction film material, but that felt too much like trying to finish someone else’s work, and somewhat disrespectful to the directors who are still alive. So, I felt that the right approach was actually to make a documentary where we could bring the films back to life, but still in their unfinished or fragmentary state. We cut together scenes from the raw footage and did Foley for them. We commissioned a score from composer Qasim Naqvi (my long-time collaborator) that combines strings and tabla with period synthesizers, which is a modern riff on the instrumentation of film scores of the time. I think what’s exciting about this format is that within the documentary, you get to dive into these moments of fiction and tap into the cinematic potential of the material, but you also get to step back and analyze it. The documentary form allows for both of those movements to happen.

But yes, it is one of the more conventionally formatted films that I’ve made. That’s probably because I worked with an editor for the first time (the fantastic documentary editor and filmmaker Ian Olds) and collaboration always changes the final form.

Film still of Yasamin Yarmal being interviewed in What We Left Unfinished by Mariam Ghani.

Alex—Can you talk about some of the stories of the directors and actors, and your relationship with them? There are so many interesting stories within even the first twenty minutes!

Mariam—I have known some of the people that I interview in the film for a while, most notably Latif Ahmadi. When he came back to Kabul after 2001, he was the first post-Taliban director of Afghan Film, the national film institute and archive, and he was in charge when I first started working with them. I’ve also screened some of his films as part of my curatorial work with the archive. His films are truly astonishing, really rich and deep. I had also met Juwansher Haidary, the head of the Afghan filmmakers’ union, and one of the first people I was able to track down when I was researching What We Left Unfinished. He was easy to find through the union, but it took a little longer to track down some of the others.

Yasamin Yarmal serves as a very important function in my film, as the voice of women in film during that time. She is completely unafraid of contradicting everything that the men say. She’s a strong feminist in her own right, and has been active in a lot of different ways in Afghanistan. She actually stayed in Afghanistan during the Taliban period, and hid herself in a remote village while she ran a secret girls’ school.

The stories that get brought out in the film have to do with how dangerous it was to make films at the time, not only that the filmmakers were targets of attacks by opponents of the regime, but also that they were working with limited resources at the time. While they had government support and access to the army, they didn’t have a studio, so there were no sets and no special effects: they were doing everything for real, on location, and (according to them) had no blanks to stage gunfights, so they just used live ammunition.

Throughout the history of Afghan cinema, there’s a real blurring of the line between document and fiction. Because so much of what happens in fiction films is real – the plot was borrowed from police files, the scriptwriter is an actual intelligence agent, all the people playing soldiers are actual soldiers— the degree to which something is staged is actually under question. Or something staged becomes real, such as during the filming of The April Revolution, a filmic reenactment of the coup d’état of 1978. When the filmmakers took down the Communist flag over the Presidential Palace, and put back up the Republican flag, some people saw this and thought the Communist government had actually fallen, since it had only been three months since the coup. There was a faction of Communist party members who were known for their luxuriant mustaches, and seeing the Communist flag come down, some of them shaved off their mustaches to hide their party membership. Hafizullah Amin, the deputy party leader, heard about this incident and had them arrested for disloyalty to the party. So there were real consequences to fake events.

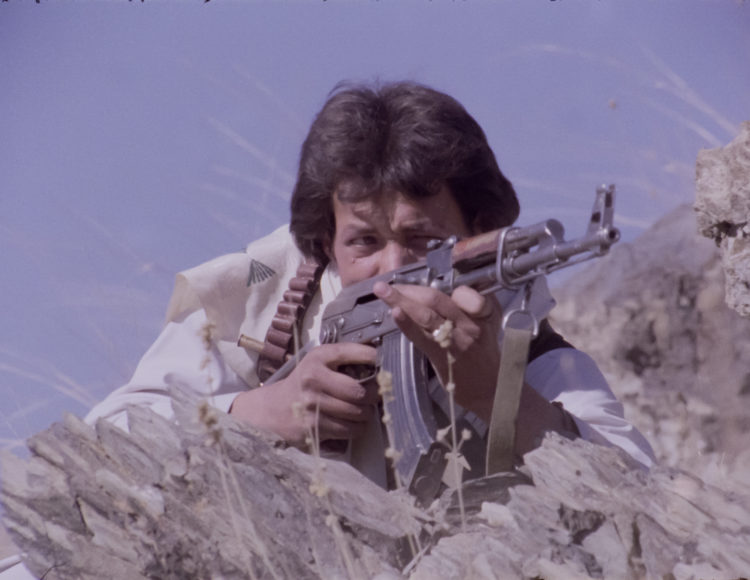

Film still from Kaj Rah starring Saboor Toukhan by director Juwansher Haidary, featured in What We Left Unfinished by Mariam Ghani.

Alex—This blending of fact and fiction that comes up in your work, using this raw material from the archive, reminds me of how W.G. Sebald uses actual photographs of anonymous people he finds in flea markets to make his fiction feel more real.

Mariam—I love Sebald, that’s a great reference.

Alex—So, what was it like to work with the archive in Afghanistan? Did you have unrestricted access to the archive?

Mariam—No, I wouldn’t say unrestricted—it’s always been a very rich but very complicated relationship with the archive. During the course of post-production, the Afghan Film archive was absorbed into the National Archive of Afghanistan, so it physically changed location and jurisdiction, the decision-makers changed, some of the staff changed, and there was a three-month period where no digitization was happening because the film reels and telecine were physically being moved and re-organized. It disrupted my timeline, and I had to rebuild my relationship with the new structure and new staff.

Archives are mutable because they’re made up of people. For me, it’s been really rewarding working with the archive because I’ve worked with some of the younger staff for years, and I’ve seen them learn and grow over that time. During production of my film, we ran a training for the archive’s new telecine setup with my DP Adam Hogan, and actually the material for my film was the first material to be digitized with the new telecine at Afghan Films. I was basically the guinea pig for the digitization process, having to give notes like “This whole section was scanned with the wrong emulsion side down, so we’re going to have to do it again.”

“The world premiere at Berlinale was also a beautiful full-circle moment, because I met Stefanie Schulte Strathaus, the head of the Berlinale Forum Expanded program, at the Creative Capital Retreat, the very first time I pitched the project.”

As my film circulates out into the world, we’re using it as an opportunity to restore and show at least one other film each time my film screens. So at the Berlinale, we were able to show a short essay film and two features directed by people I interviewed, one of which also stars Yasamin Yarmal, Latif Ahmadi’s film Hamas-e eshq (Epic of Love). In Berlin, two other stars of that film were able to come to the screening because they were already living in Germany, and their kids came as well because they’re married to each other! He’s also in my film, because he’s the star of Agent, and appears on the poster for my film.

For the SFFILM Festival, we’re trying to restore Wali Latifi’s film, Difficult Days, since he’s living in San Francisco. We’re going to try to finish restoring and subtitling this film in time to show it after the festival, because some of his family out there have actually never seen his film. So, it would be really neat to screen it for them in San Francisco—it hasn’t been seen since the ‘70s.

Alex—As you mentioned, your film is going to be in the San Francisco International Film Festival. Are there any other reasons, besides what you just mentioned, as to why it’s a good place for its premiere?

Mariam—I’m really excited for it to premiere in San Francisco because there’s a big community of Afghans in the Bay Area. Also because San Francisco is a bit of a hub for Asian foreign policy. So for those reasons it’s a great place for the North American premiere of the film.

The programmers at SFFILM really love What We Left Unfinished, and it’s always nice to show at a festival that supports the film whole-heartedly. The world premiere at Berlinale was also a beautiful full-circle moment, because I met Stefanie Schulte Strathaus, head of the Berlinale Forum program, at the Creative Capital Retreat, the very first time I pitched the project.

Alex—That’s great! How else has Creative Capital helped you with the project?

Mariam—EMPAC—where the retreat was hosted in 2015—gave me a post-production residency, where I did all my sound for the film, and the first pass of the color grading. That was an incredible help for finishing the film—especially because I had run out of money and I couldn’t afford to finish it otherwise. Particularly because all the archival footage was silent, and doing Foley for it made an enormous difference in waking the footage up, and making it feel like film rather than document.

At EMPAC, we did the Foley in this super-DIY manner, where we built our own mini-pit, and collected sound-making objects from the theater prop department and the shop, and just experimented. I would estimate that 70% of the footsteps you hear in the film are mine. But DIY is how they would’ve done it at the time, so it feels very authentic.

Read more about Mariam Ghani’s film and see it at the San Francisco International Film Festival.