Brian Harnetty Turns Deep Ethnographic Research into Music in Shawnee, Ohio

Who can tell the history of a town as it evolves? Brian Harnetty is a musician who makes work around his own ethnographic studies of regions in America. For his Creative Capital Project, Shawnee, Ohio, he focused on the small Appalachian town where his family came from, studying the area’s complex history of mining, labor, and culture from the 19th to 21st centuries. Using images, video, audio recordings, and archival materials, Harnetty composed an album of music and performance that blends all of this to tell the story of Shawnee—its heyday, downfall, and recent revival. Harnetty also blended the performance and music into a film, which will be screened during a free digital event on Wexner Center of the Arts‘ website on March 9, 2021, then available to watch free online through March 23.

We spoke to Harnetty about the story of Shawnee, what the town looked like at its peak, and the people behind some of the archival recordings.

Alex Teplitzky—Tell me about the project in a nutshell.

Brian Harnetty—Shawnee, Ohio is a series of audio and visual portraits of everyday people from a small Appalachian town in Ohio. It uses archival recordings, video, images, and creates a collage of these people’s voices to express the life and history of the town. That includes its buildings, the labor of the people there, disasters relating to mining and extraction, and also their hope for a future that isn’t based on extraction.

Appalachian Ohio has a long history, ever since white settlement, of booms and busts, and extraction through coal, oil, gas, clay, iron ore or timber. The people that have lived there for the past couple hundred years have a strong labor history—the United Mine Workers was secretly formed just down the road in New Straitsville. There’s also a lot of stories about recovery there. The forest which was completely clear cut a century ago has essentially returned.

Shawnee, Ohio tries to capture these different stories and brings them together using archival recordings and my own ensemble of seven musicians as a series of portraits in the people’s own voices, speaking about the town, labor, disasters, protest, or recovery. There’s singing too, where people sing traditional murder ballads or more hopeful songs.

Alex—What’s your connection to the region?

Brian—I’m from Columbus, and I don’t identify as Appalachian, but my dad is from Appalachian Ohio, and my mom’s family is from Shawnee. So I have kind of an insider and outsider status. I feel a strong connection to the people and place, but I also have a bit of detachment. I try to look at it critically, and try to understand it compassionately to figure out residents’ pride, and ways to make it better in the future.

Alex—I loved learning about one piece in which you play a recording of a boy who interviews his grandmother about an explosion at a mine, and the people who died there. In the recording, the boy asks questions but he doesn’t manage to record her answers. The song really brings you into the room with them. What other stories are illuminated through the piece?

Brian—Yeah, I also really enjoyed the vernacular quality of the voices. They seem relaxed and engaged in their conversation, it never feels forced.

There’s one piece called “Judd.” This man has a rich, deep baritone voice. Judd was a mine inspector and he had a long history of working in the mines. He grew up watching his dad work in the mines, not being able to own land, and beholden to the mining companies. He told cautionary tales about cave-ins and the mines, and how people didn’t always get out of the mines. I was touched by that.

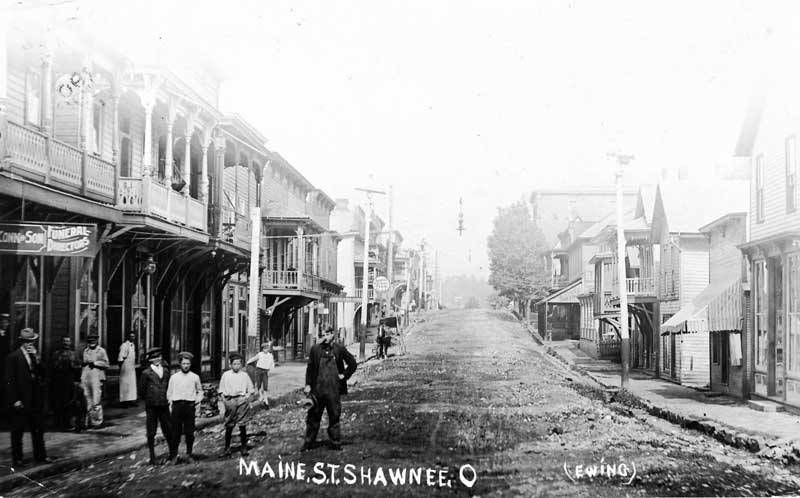

Image courtesy of the Little Cities of Black Diamonds Archive.

There’s one by Sigmund Cozma, who was the last living survivor of the Millfield Mining Disaster, which took place in the 1930s where 80 miners were killed. The way that he spoke about his fellow miners who had perished was very touching. It also became a cautionary tale for the boom and bust cycles and extraction, and what kind of damage we’re doing today.

There’s a woman named Neva Randolph. She was on her deathbed, and people came to hear her sing. When she started to sing, she perked up and became full of life again. And the song she sang—somewhere between a hymn tune and gospel—reflects her Affrilachian heritage (the term for African-Americans of the Appalachian). I thought that was a really nice, hopeful way to end the project.

Alex—How did you discover these recordings?

Brian—Part of the recordings were from the Anne Grimes Collection, which is located in the Library of Congress. She made most of her recordings in the 1950s and ’60s. Those are very well-documented recordings, and that includes some of the traditional songs and murder ballads that were sung.

The other recordings were created by the community members themselves, mostly in the 1980s and ’90s. This was an effort by them to capture the stories of that place before that generation passed on. It also helped redefine the region and see it in a more positive, diverse light that also pushed against stereotypes—not only focused wholly on the idea of poverty, or that there are only white people there, or that they were helpless. It was a really wonderful set of recordings, but they were just handed to me in a cardboard box as a group of cassette tapes. I took up the task of transcribing and digitizing all of them. In doing so, it helped me learn about the region in a more intimate way.

The other quality that I like about those recordings is that you can hear the grain of people’s voices, you can hear their vulnerability, or their laughter, you can hear in-between moments like when a door closes or the birds outside. All of those things contribute to the richness and the complexity of the recordings.

Image courtesy of the Little Cities of Black Diamonds Archive

Alex—So, then did you take the recordings and make music out of them, or did you have music you were already working on? How did you blend the music into it?

Brian—All of my projects have a really long research period, and this one was the longest. I spent about five years doing ethnographic work in the region, and writing about it, before even tackling this project. Part of what I do is research the music that people may have been listening to, or performing, or playing at that time. Since my own grandfather was from Shawnee, I was able to pinpoint that he played saxophone and piano with the Shawnee Orchestra. I was able to find some of the sheet music that he performed along with other community members. I also found a lot of old labor songs from the 19th century, from the Knights of Labor, and a couple other small labor groups from the town.

From there, I transcribed the sheet music and spun that out into my own music, the idea being that there’s a certain logic to the music. It’s connected—not exactly, it’s not quotation, but it’s connected somehow to the music people were listening to when the recordings were made.

Alex—Can you paint a picture of Shawnee as it has evolved over the last century, from its heyday to now?

Brian—Sure. So, about 40 years after the Shawnee people were forced to leave the region, the town of Shawnee was founded in the 1870s and it was directly connected to the coal mining boom in the region. That’s when my mom’s family moved there—they moved there as Welsh coal miners. The way that it looked in its heyday, which would have been at the turn of the 20th century, there were two- or three-thousand people there. There was a thriving main street. They had not only one, but two opera houses, which was pretty stunning for such a rural place. It’s been joked that it was called “the Paris of the coal fields,” and that kind of stuff.

By the 1920s, there were labor disputes. There was also an underground mine fire that started nearby in the 1880s and ravaged under the ground. Those combined events along with the Great Depression really sent the town into a spiraling economic depression. It has remained in that state since then. For nearly a century it’s been essentially economically declining. I think there are about 600 people living there today.

The interesting thing about it is that the whole area was clear cut of all the old growth trees. As part of the Franklin Delano Roosevelt New Deal, the whole area was designated as a National Forest without any trees in it. Maybe the biggest difference today is that now the forest has returned. Now, the town is completely surrounded by trees that are 80 years or so old. It’s a very beautiful place. You drive down a hill and you see it rising up against the back of another hill. You can see the opera houses and the remaining buildings that are there.

When you drive into town, it’s a little different—many of the buildings had to be torn down because they weren’t structurally safe. There aren’t many businesses there at the moment. However, I think it’s changing. I think it’s having a revival, and one not necessarily based on extraction. So, I think there are actually a lot of exciting things happening to the town recently.

Alex—And at the end of the film there is newer footage, so it seemed like you are hinting at something more recent.

Brian—Yes, that footage is from 2016, and that’s even before some of the revival happening right now. I worked with a filmmaker and cinematographer named Jon Johnson, doing some of the contemporary images to balance the archival footage.

Alex—You’re premiering this project at the Wexner. Can you talk about that?

Brian—Shawnee, Ohio was originally a live performance. I have my own group with eight performers. We had video playing at the same time of the archival images and video of the town. Obviously, during COVID it’s been harder to do performances. We had some great performances at the Wexner, who was the lead commissioner of the project, along with co-commissioners Duke Performances and Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati. It had many other performances, too, such as the Liquid Music Series in the Twin Cities, and even in the town of Shawnee, performing for local residents.

So, I felt like it had a nice performance run, but I also felt that the project translated really well as a film. I’ve been working to reedit the visual material, and bring it together with the album version of the music to create this new film. I think it adapts well to the medium. It captures the essence of live performance, but also allows the viewer to get lost in some of these landscapes and voices. So it was a perfect mix.

Alex—You mentioned you did a lot of research for this project. Was Creative Capital helpful in any of that?

Brian—It’s been five years since receiving the Creative Capital Award, and it’s been a complete game changer. It’s completely changed the way I think about how my work lives in the world. It’s also taught me how to communicate with other people. And this is in addition to the financial support.

It’s opened up all of these possibilities that I’ve pursued since then. When I received the award, I had recently finished a PhD, and I was moving between the academic world and the creative world. Creative Capital allowed me to have a home base and a place to establish myself as a creative artist who does a lot of research, and tries to bring all those worlds together.

They also allowed me to work very deeply on the project. I didn’t just bring it to a premiere and then let it go, which seemed to happen a lot before that for me, partially because I was excited to start new projects. But they urged me to slow down and develop strong relationships with both national presenters and the local residents of Shawnee. What that’s meant is that all the projects I’ve been doing alongside Shawnee, they have all been complementing one another, and it’s allowed me to have a larger sense of my own work.

Sign up to watch a digital live screening of Shawnee, Ohio at the Wexner Center on March 9, 2021.