The Ripple Effect of History: A Documentary about a Group of Radical Activists Resonates Today

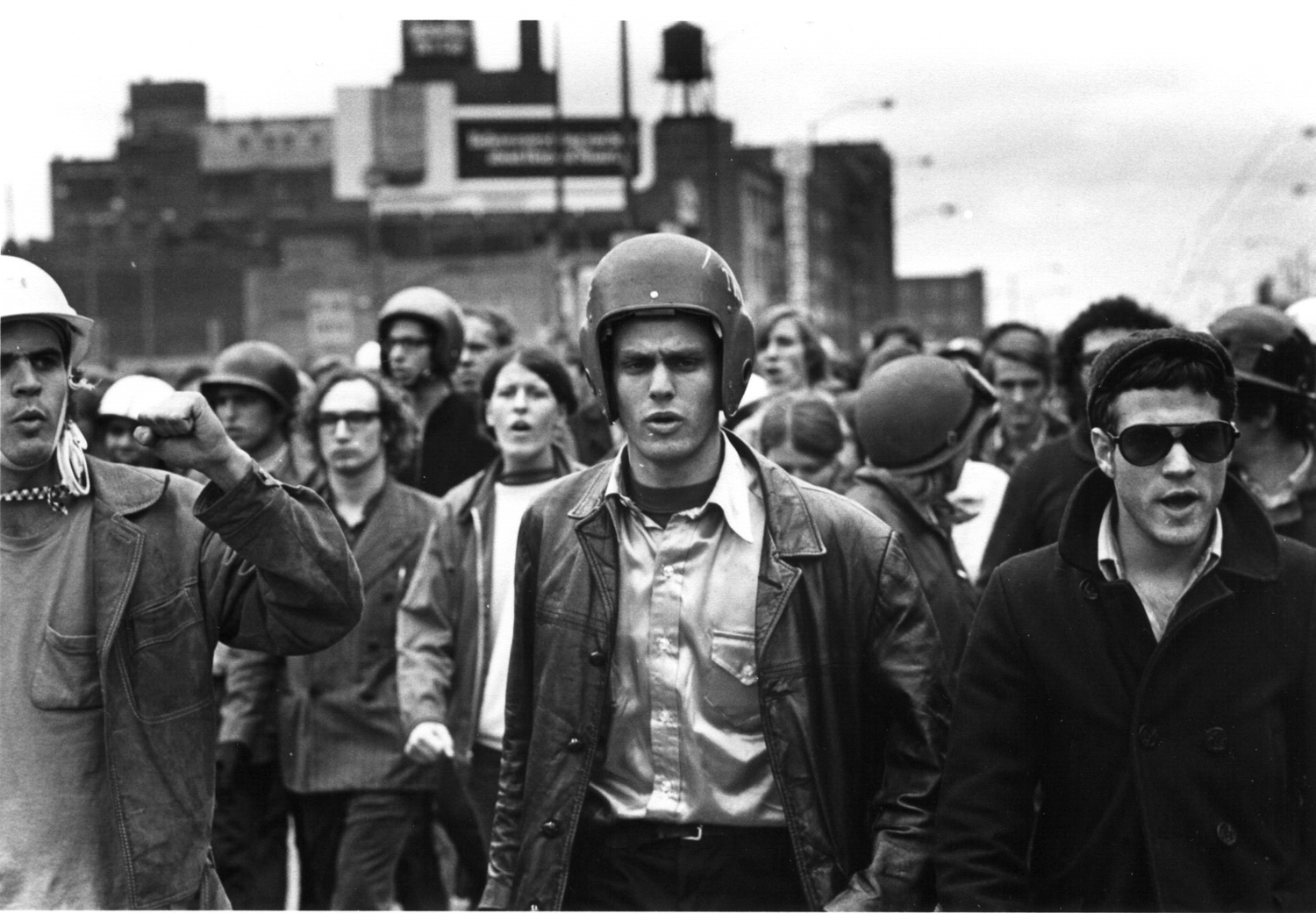

John Jacobs at left and Terry Robbins at right at the Days of Rage, Chicago, October 1969. Photo: David Fenton/ITVS. From The Weather Underground by Sam Green and Bill Siegel

As a more diverse group of Americans join the movement led by Black communities to demand an end to police brutality, some look to historical movements for lessons, among them the radical activists, the Weather Underground. In the hopes of rousing white Americans to the violence being committed by their government, the Weather Underground organized in the late ’60s against the systemic racism that shaped US policy at home and abroad, gaining international attention and criticism through their actions. Sam Green received a Creative Capital Award in 2001 to make a documentary about the movement: The Weather Underground, made in collaboration with Bill Siegel, premiered in 2002 and was nominated for an Academy Award. Green pointed out that although the Weather Underground were “morally right, but strategically” wrong, their story provides a complex, yet instructive example of what happens when a group decides peaceful protest isn’t enough.

In the late ’60s, a group of activists in the Students for a Democratic Society organization began to feel that their protests were not being heard. They were working to rise up against white supremacy, the Vietnam War, and other acts of violence committed by the US government, and they felt that white America, as it remained silent in the face of this violence, was complicit in these crimes. This group decided to go underground and bomb buildings, without harming anyone, in the hopes of calling attention to their struggle. “They stayed one step ahead of the FBI for about ten years,” says Green, “and during that time, they didn’t hurt or kill anybody. It was symbolic violence.”

Asked what interested him about the Weather Underground, Green responded, “the story of the group was infinitely complicated to me and still is in a way because I sympathize with what they did.” When he was living in the Bay Area, a friend of a friend introduced Green to a former member of the group. He was surprised and moved by the conversation: “I had always thought the Weather Underground were this crazy group of young people who went off the deep end, had group sex, took acid, and started bombing things,” he said, “but he was a really smart, serious, and articulate person.” It inspired him to imagine what he would have done in their place, and to ask himself, what is a person’s responsibility for the actions of their government? “You know, complicated questions. I really appreciated the moral ambiguity at the heart of the story.”

Green went on to make the documentary, in part, because he felt that the 1990s were a politically vapid period in the US. “There was a lot going on under the surface, but not so much discussion of it in the broader culture,” he said, “I was drawn to make the film because it was so strikingly different from the tenor of the times.” The contrast between the current moment, and the violence and politics of the late ’60s and ’70s felt stark. The mission of the Weather Underground—of waking white Americans to violence committed by the government in their name—felt so far removed from the world of the ’90s.

“I saw the value and rightness of what they did, but at the same time I could see a criticism of them. In some ways it came down to—morally they were right, but strategically they weren’t right.”

Above all, it felt radical. In response to people who pointed out that the Weather Underground’s tactics were violent, Green quoted member Naomi Jaffe, who says in the film, “We felt that doing nothing in a period of repressive violence is itself a form of violence.” She went on, “if you sit in your house, live your white life and go to your white job, and allow the country that you live in to murder people and to commit genocide, and you sit there and you don’t do anything about it, that’s violence.”

It was a line that felt so radical to Green making the film in the late ’90s that he almost didn’t keep it in the documentary. “White people didn’t really talk about whiteness so much back then,” he said. By chance, Siegel’s mother, after viewing a draft of the film, insisted that it be kept in. “I was trying to make something that would work with a broad audience,” Green explained, “young people who were not political at all.” He thought that the line would turn people off, but looking back on it, he now felt that Siegel’s mother was right—it was key to understanding the motivation of the Weather Underground.

The Weather Underground felt that the atrocities being committed against Vietnamese people and in Black communities were too abstract for most white Americans—it was easy to turn a blind eye toward police brutality and war. Bombing buildings without hurting anyone was the Weather Underground’s way of making the violence more real for people, bringing the violence to their home turf, in the hopes of rousing them. Today, with the help of social media and smartphone cameras, this violence is more visibly documented—and more white Americans admit that their silence perpetuates marginalization, as publications like New York Times and Los Angeles Times have reported.

Green stressed that his documentary was not uncritical of the Weather Underground and their tactics. “Violence is complicated,” said Green. “If you put violence out, it can quickly do things that you didn’t intend for it to do.” The documentary shows a timeline of various bombing events, and which issues the Weather Underground were using the bombings to speak out against—for example, the FBI’s murder of Black Panther leader, Fred Hampton in 1969, and the killing of 29 inmates at Attica State Penitentiary in 1971. Looking back on these actions, Green commented, “I saw the value and rightness of what they did, but at the same time I could see a criticism of them. In some ways it came down to—morally they were right, but strategically they weren’t right. They thought their violence would galvanize and create a movement, and it didn’t.”

So, is the Weather Underground important now? Certainly, the story of the Weather Underground—a group of less than 100 people—resonates today with the desire of young Americans to affect change. If the group’s movement didn’t necessarily lead to direct action from the people they were hoping to speak to, they did indirectly. Green explained that many in the group were inspired by John Brown, a 19th-century white abolitionist who led an armed insurrection in Harper’s Ferry to overthrow the institution of slavery in the US. He had failed, but his struggle had not been forgotten. As the group was inspired by Brown, Green said, “I think the Weather Underground are worth keeping in mind, especially for white people, in thinking about how we engage with the times.”

Despite continued stay-at-home orders, many have decided to join protests, some for the first time in their lives, to speak out against deep-rooted systemic racism. Reflecting on how many young Americans of all backgrounds have found The Weather Underground documentary as a source of inspiration, Green said, “the ripple effects of history are an ongoing process. The story of the Weather Underground inspired people after the Iraq War, and the protests around that. Movements for social justice continue ever onward: “it’s a dialogue between the past and present,” said Green “and it’s constantly changing.”

The Weather Underground is available to view on Amazon Prime Video.