How To Write a Grant Proposal With Confidence: Translating Your Ideas on Paper

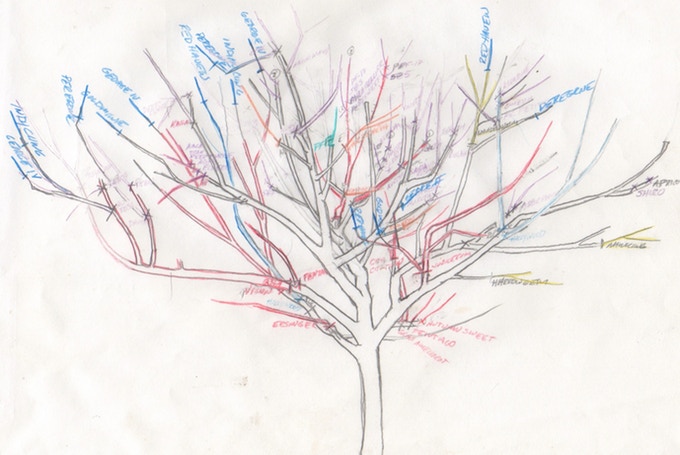

Creative Capital Awardee Sam Van Aken’s diagram showing the multiple grafts on a single tree for his project Open Orchard on Governor’s Island

When you are ready to begin fundraising for the your next creative endeavor, it can be difficult to translate those ideas to project descriptions, budgets, and timelines. Tracie Holder, who leads Creative Capital’s workshops on Grant Writing, has a few tricks and tools to help you put your ideas to paper—after you do the initial research on funding organizations—so that you can write a strong grant proposal.

Use Applications and Grant Proposals as Tools

“A grant is a snapshot of the project in time,” says Holder. The timeline of your scope of work, the project description, the impact you hope it makes, even the budget, all should help funders understand your thinking and paint an overall story of how your project will come into the world. Proposals aren’t the work, meaning the art or project, itself. Instead, Holder suggests thinking of them more as the blueprint of a building—they are just a theory of the project, but their goal should be to give the funders a vivid sense of the project so they can imagine it existing and “see” it in their mind’s eye.

Whatever the trajectory of your project, the way you write about it should make your passion apparent to funders. Speaking of her experience sitting on funding panels, Holder says, “sometimes I’ll read a proposal and the project feels inevitable… every detail has been thought out and that comes through on the page.” The goal is to make a funder feel like the work will get made with or without their support, so that they have confidence in both your artistry and ability to execute it if funded. Make the funder feel like you’ve anticipated every possible obstacle and detail, planned accordingly and will let nothing will get in the way of you realizing your project.

Thinking about the competition when you submit your proposal can give you a fresh perspective on your work. Holder mentions a documentary film project about architecture by a friend of hers. If it was submitted to an organization that funds documentaries, it would have been competing with a huge number of other documentaries. However, the friend submitted the project to an organization that funds projects about architecture. As a documentary, it was unique in a pool of architecture-influenced artists. The artist was able to isolate the project as a distinctive vision.

The strongest proposals, Holder says, strike a balance between context and specifics.

Form Groups to Help Articulate Ideas on Paper

One of the main issues that comes up when Holder helps artists apply for funding is maintaining critical distance when describing the work. “Artists,” Holder says, “myself included, are so often swimming inside the fishbowl of our own minds, and living with our ideas that we have trouble successfully conveying a fully realized vision to a potential funder. We often imagine that what’s clear to us is self-evident without realizing that we need to step back and make sure we’re providing a comprehensive window onto our process, how we plan to get from concept to completion, and what exactly the final work will be.”

For example, often an application might fail to mention basic information about the work, like whether it’s an installation, what it’s made out of, or what kind of media it uses. It’s important to use descriptive, visual language when speaking about your project so it comes alive for the funder and they too can imagine what you have in mind.

Holder suggests that you choose friends who both are and are not familiar with your work. Showing them grant proposals will help determine whether what you have written accurately expresses what you’re hoping to accomplish with your practice. “We’re so immersed in our projects and rarely can maintain critical distance. It’s nice to have someone to come to our work with a fresh set of eyes and give us a reality check. Am I conveying what I had intended? Is anything unclear?” says Holder.

Visit Museums to Influence How You Write About Your Work

When writing about your work, Holder suggests thinking of yourself as a curator who is writing a wall blurb to accompany the work in an exhibition. In essence, your project descriptions should invite the funder to understand the creative process informing the work you are proposing and how you plan to go from concept to completion.

The strongest proposals, Holder says, strike a balance between context and specifics. Like the wall blurbs at a museum, your project description should tease a vision of a bigger universe that will entice funders and panel reviewers.

Next time you go to a museum, picture what the wall blurbs accompanying your work might say. This might help give you the critical distance you need to write an exciting grant proposal to funders who are unfamiliar with your work.

In Holder’s workshop, as an exercise, she asked the artist participants to write a review of their own work, as if they were an art critic, and the work was completed. Reviews only give readers a brief overview of an exhibition, film, play or book but they cover the essential details. They don’t dwell in the weeds. The same is true for a good proposal. What are the main themes of your project? What are the textures, how is it organized? You don’t want to show each painting of your imagined exhibition, but give the reader an overall, big-picture sense of what they will take away after seeing it.

The more grant proposals you read side-by-side, the easier it is to recognize what makes for an outstanding application.

What to Do After You Receive an Answer from a Funder

Remember, Holder says, all funding is first and foremost about relationships. When an application or proposal is successful and you receive a grant from an organization, you have a place to begin next time you work on applying for funding. Study carefully your successful grant applications to help you make informed decisions about how to write about your next project, or even how to best conceive your work. Often, the fundraising process helps artists move the project forward regardless of its success as a grant proposal.

Often working in groups with other artists and sharing your proposals with each other helps cut down on feeling isolated and also can provide valuable feedback. Groups that you formed when writing proposals should continue to meet even after individuals have received acceptances or rejections. The more grant proposals you read side-by-side, the easier it is to recognize what makes for an outstanding application. Organizations rarely share past applications, so forming a pool of applications in which you share writing could work to everyone’s benefit regardless of the outcome.

Artists who inspire confidence tend to be good fundraisers, so don’t be intimidated by the grant writing process.

Sign up to our email newsletter to receive updates on when Tracie Holder leads Creative Capital’s next online or in-person workshop.