Heather Dewey-Hagborg Imagines How Our Biodata Could Be Hacked

We’re just starting to become aware of how digital companies are using our data, but what about our biodata? This question is at the heart of Heather Dewey-Hagborg’s Creative Capital project T3511, which premieres May 11 at MU Artspace in the Netherlands. The four-channel video installation tells the story of a biohacker who secures saliva from an anonymous donor to extract the person’s DNA, grow their body in a petri dish and proceeds to fall in love with them. The work is an imaginative look into what might be possible in a matter of years.

We spoke to Heather about her work.

Alex Teplitzky: Usually I start by asking people to describe their project, but I feel like with your work, there is a personal narrative about how you arrived at this subject matter.

Heather Dewey-Hagborg: Yes, all of the work that I do critically reflects back on the work that came before it. In particular this growing body of work that I’ve been creating since 2012 deals with biopolitics and the biopolitics of data—very personal, intimate, bodily data, specifically DNA. T3511 is, in a way, a critical grappling with all of the elements that have come before it in my work, and it folds into a more personal narrative that puts me as the subject at the center of the work.

I’ve been working in the area of AI and machine learning since I was an undergrad in 2001, and surveillance since about 2007. Then in 2012 I had this pivotal experience where I was sitting in therapy and I noticed this painting across from me on the wall. The glass that was covering the painting was cracked and there was this hair stuck in the crack. It’s a story I’ve told many times, but it really was this critical experience where I was staring at this hair for an hour and just wondering about the person who might have left it, imagining what I could learn about them from this piece of them that they had left behind.

That launched me into this journey that became Stranger Visions. I walked around the streets of New York and collected genetic detritus, like cigarette butts, chewed up gum, and pieces of hair and fingernails that strangers had left in public. Then, I took those to the world’s first community biology laboratory that had just opened in downtown Brooklyn called Genspace. There, I learned how to extract DNA from those samples, and how to amplify it, and how to analyze it. I started generating genetic profiles of these strangers. Then, I put that together with the work I had been doing around facial recognition and facial generation and I started to create these computational, probabilistic portraits that represented what those strangers might look like based on genomic research. So, I would generate 3D models of the strangers and I would 3D print them in full color. I exhibited them as life-size full color portraits alongside the genetic material that they were generated from.

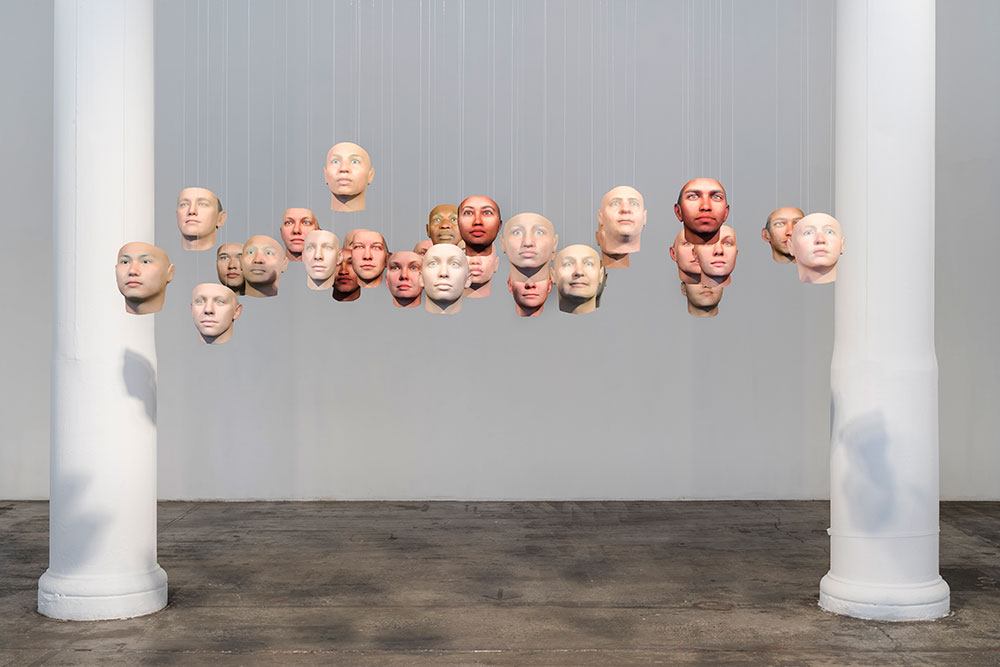

“Probably Chelsea” by Heather Dewey-Hagborg, displayed at Fridman Gallery.

Alex: So, you were doing that work and all of a sudden you started working with Chelsea Manning?

Heather: That’s right. In July of 2015 I was contacted by Paper Magazine and they were doing an interview with Chelsea Manning through the mail. They wanted some kind of visual portrait of her to accompany their interview. They remembered the work I did with Stranger Visions and had this idea of doing a DNA portrait. So, they brought it up to Chelsea first, and Chelsea had also read about my work, and she thought the idea was totally exciting. They contacted me and that was the beginning of my relationship with Chelsea.

She sent me hair clippings and cheek swabs, and then I extracted DNA from that, and went through the same process that I went through with Stranger Visions. Except Chelsea was concerned about appearing too masculine because of her genetic gender identity. That became a perfect opportunity to push the whole project a bit further in a critical self-reflective direction. In the first iteration of the work, called Radical Love, we decided to generate two versions of her portrait that would hang side by side, one that was algorithmically, so to say, ungendered, more androgynous, and one that would be algorithmically “female.” We hoped that by putting those side by side it would call attention to some of the reductionism and short comings of these technologies, and to provoke people to think about what a female face would even mean, or what it meant to have an algorithmically female face. We were really hoping to provoke questions around that and questions around this new technology.

Alex: I really loved following that work. I remembered after Chelsea’s sentence was commuted by President Obama, Chelsea was all over the news. The power of your portrait of her was transformed, and it became something different. When she was in prison, there was just one low-res image of her circulating that she had taken herself. So, at the time it was incredible that you were able to develop a portrait of her through this new technology.

Chelsea: Exactly, at the time it was so powerful because her image had been completely suppressed. No one was allowed to visit her or photograph her. We premiered the 3D prints of her portrait at the World Economic Forum, so we really intervened and put her face front and center in front some of the most powerful people in the world. When I look back on it, I’m even more amazed than I was at the time. I was just going along, doing my work. Then I stepped back a couple of years later and was like, “Whoa! That was amazing that that happened.” It was incredible.

The follow up piece, Probably Chelsea (30 versions of her portrait) was the celebration of her release. That was where we had written this comic book together that forecast her release from prison, called Suppressed Images, and then it came true, which was amazing. We had this gallery exhibition as it was forecast in our comic book together. We wanted to push it even further and really make it a collaboration. That’s where Probably Chelsea came from. This is one the works that will be in the show at MU. It pushes that questioning of determinism and reductionism even further by showing 30 different possible Chelseas that are really very diverse, showing how many different ways you can interpret the same DNA data.

Also, in that work for the first time I started taking the portraits off the wall. Before that, in Stranger Visions, I was always hanging the 3D portraits on the wall. In Probably Chelsea, I started hanging the portraits in mid-air so that they would hover there, and all together would evoke the feeling of a crowd or a mass movement that was standing with Chelsea.

Alex: So that brings us to T3511. All this past work informed that project—it’s a fictional retelling, but partly true, and you’re dealing with the same issues.

Heather: Exactly. T3511 deals with a lot of issues simultaneously, but one of them was the realization I had that the work I was doing with Chelsea’s DNA was so incredibly personal. I moved from working with this panel of strangers to suddenly working with this one person’s DNA, receiving this person’s bodily material in the mail. I was sitting there with it, spending time with it, thinking about it, touching it, extracting the DNA, dealing with the data, researching it. I got to know this person through their data, their cells, rather than through messages or letters or even having met them. None of that happened until later. We had never communicated when I started working with her DNA.

A year later reflecting on it, I realized we had this very intimate relationship even though we had never met. That started to inform the work I did in T3511, which is all about falling in love or becoming obsessed with someone that you’ve never met, just through profiling their data, and working with their bodily material, in this case saliva and cheek cells.

Alex: Can you describe the work?

Heather: It’s a four-channel video installation, a ten-minute narrative piece that follows a biohacker, that’s me. I become increasingly obsessed with this anonymous saliva donor. It starts with the biohacker purchasing the saliva online and sending it off to different genetic profiling companies, and also beginning to culture their cells in a petri dish. Then it gets a bit stranger and intense, more intimate and personal. And you realize it’s an unrequited relationship—that the biohacker is more into this person than they are into her.

Alex: Your work is often speculative fiction, but you’re playing with cutting edge technology that actually exists. So it’s not just speculative, these are very real possibilities. The idea of taking someone’s data and being able to download it, and access it, and do what they want with it, is super real for people right now, right?

Heather: It’s so interesting how it’s changed. I’ve been working on this piece for about two years. The context has definitely changed pretty dramatically. When I started working on it, it began with research into biological commodification. I was looking at the legacy, for example, of Henrietta Lacks. She was an African-American woman who had cells taken from her in the 1950s at Johns Hopkins Hospital, and turned, without her permission, into the first ever, immortalized cell line. It’s been the subject of lots of articles, books, movies, and a book made into a movie starring Oprah. It was a much-discussed case of biological exploitation: using someone’s body, their data, their cells and DNA without their permission and making lots of corporate and academic profits off that. I became really curious, in reading about Henrietta Lacks, in how widespread the practice actually was. I began to wonder how much we are all participating in a network of biological exploitation without knowing it. So, I started digging into that research and I realized that indeed our bodies were being used all the time without our permission.

The twist that happened also in thinking about that, very much as a parallel in what happens with our digital and electronic lives, where we’re semi-knowingly giving away our data to be exploited, and a similar thing happens in the biological realm with companies like 23andme and ancestry.com. Each has a million users or participants who have sent them saliva and received a genetic profile, and more or less knowingly given away some amount of their privacy. It’s really a question of how much, and how much people understand of that, and what is the awareness of the implications of all that? We’re really in the early days of biological information. We’re just now understanding the implications of Facebook and Google, and what happens with all that digital information, so we’re quite a bit away from understanding what happens to biodata.

That said, the case with the Golden State serial killer is an interesting one because it’s been all over the news. Suddenly it’s giving the public a lesson in biodata privacy, and showing how easy it is to track someone down through their relative’s DNA. It’s not just about what you and what you choose to do with your biologic information, but you also implicate your family members and relatives as well.

Alex: There’s so much at stake, I can’t imagine how it all ties together in the project.

Heather: I was researching biological commodification, while I was thinking about my relationship with Chelsea, and thinking about other romantic relationships, and everything got kind of blurry and overlapped in a way in the writing. The whole narrative of the video is told in a voice over in this series of love letters that I’m writing to the saliva donor. The donor is this pastiche of all of these different characters, people I love or have loved, or strangers whose DNA I’ve spent time with. It’s meant to call attention to this data relationship as being actually an intimate one that we should all take a little more seriously.

Alex: Whenever I read about your work, I think about all this technology and science you’re working with, and I have to remind myself that you’re first and foremost an artist. It’s so overwhelmingly driven by these huge implications, that it’s easy to forget that this is art. How do you balance the disciplines?

Heather: I don’t know! I never worry about it too much. I studied art alongside computer science in undergrad, so it’s continuous territory for me. I’m lucky to have engineering as a tool at my disposal alongside the more artistic toolbox. I think I just try to focus on concepts and questions and see where they lead, and try to be really authentic to my interest and my research in the project, and not get too caught up in worrying whether it looks like art or not.

But I have to say that this piece, T3511, is definitely a departure for me in that it’s so incredibly personal. That’s not something that I’ve put out into the world before. It’s intimidating to share so much suddenly about myself.

Alex: I’m excited to see it! Can you talk about how Creative Capital was helpful to the project?

Heather: Absolutely. Creative Capital has been amazing, so supportive. I love that this idea was just a seed when I wrote the proposal three years ago. I didn’t really know what it was going to be at all. I just had this domain of interest that I was looking into. I love that Creative Capital took a chance on the project in the first place in supporting me.

I would also say that through the Creative Capital network, I’ve met so many amazing artists, curators, just great people that have become friends and have not only helped the project, but have just become part of my personal and artistic life. So I’m really full of gratitude.

T3511 will be on view at MU Artspace in the Netherlands May 11 – June 8, 2018.