Bruce Yonemoto and Juli Carson Connect an Actual Growing Glacier, Lacan and "Fake News"

It’s hard to imagine that there has ever been a time when the globe’s natural history was so intertwined with the world’s political history. Bruce Yonemoto and Juli Carson poetically speak to how several issues demonstrate this connection in their Creative Capital project, The Edge of the World at the Edge of the Earth, premiering at Luckman Fine Arts Complex in Los Angeles (March 25 – May 13). The digital and film installation brings together one of the last expanding glaciers located in Argentina, the burgeoning Lacanian practice in that country, and Argentinian psychoanalytic theorist Oscar Masotta, whose “anti-happenings” are uncannily related to today’s “fake news.”

We wanted to delve deeper into these issues, so we caught up with Bruce and Juli.

Alex Teplitzky: The project combines a few things that rhyme with each other happening in Argentina. Talk about the first one: the last growing glacier in the world. I didn’t know there even was a glacier !

Bruce Yonemoto: While globally glaciers are shrinking, there are isolated areas where glaciers are growing. Patagonia, home of the Perito Moreno Glacier, is one such area. The Perito Moreno Glacier is one of only three Patagonian glaciers that are not retreating. Periodically the glacier advances over the L-shaped “Lago Argentino” (“Argentine Lake”) forming a natural dam that separates the two halves of the lake when it reaches the opposite shore. With no escape route, the water-level on the Brazo Rico side of the lake can rise by up to 30 meters above the level of the main lake. The enormous pressure produced by this mass of waters finally breaks the ice barrier holding it back, in a spectacular rupture event. This dam/rupture cycle is not regular and it naturally recurs at any frequency between once a year to less than once a decade. The glacier first ruptured in 1917, taking with it an ancient forest of arrayán (Luma apiculata) trees.

The last rupture occurred in March 2006, and previously in 2004, 1988, 1984, 1980, 1977, 1975, 1972, 1970, 1966, 1963, 1960, 1956, 1953, 1952, 1947, 1940, 1934 and 1917. It ruptures, on average, about every four to five years. The last rupture was in March-April of 2008.

As a poetic means of approach Juli Carson and I are interested, metaphorically, in the convergence of migratory historical/cultural events and the glacier’s years of rupture. For instance, Perito Moreno’s rupture of 1917 converges with the Northern Hemispheric events of the October Revolution in Russia, the invention of the readymade by Marcel Duchamp, and the proliferation of semiotic theory by the Moscow group. While the Perito Moreno’s rupture of 1966 converges with the Argentinean military coup led by Onganía, the art Happenings led by Masotta, and the proliferation of Lacanian theory by the academy in the South Hemisphere. Interestingly, the 1917 rupture coincides with the European “historical avant-garde.” The 1966 rupture coincides with the Argentinean re-interpretation of the European “neo-avant-garde.”

Alex: I love the idea of showing how natural history and human history coincide. The other two issues addressed in your project are the Lacaninan practice happening in Argentina and the anti-happenings by Oscar Masotta. Can you tell us about those, and how they connect?

Juli Carson: The first connection we made upon endeavoring this project—the connection between “the last growing glacier and the last growing Lacanian clinical practice”—was originally conceived as a kind of poetic “tongue-in-cheek” proposal. One we meant to provoke people in the surrealist, philosophical sense. I personally always thought that the way a glacier “grows” through ruptures—specifically a land-locked one like Perito Moreno—evoked the process of the unconscious, which also ruptures our thoughts through slips of the tongue and what not. So we just kind of went with it: the glacier being the “natural embodiment” of the unconscious in a land where tapping into people’s unconscious was a major industry, in terms of the 1000s of Lacanian psychoanalyists populating Buenos Aires.

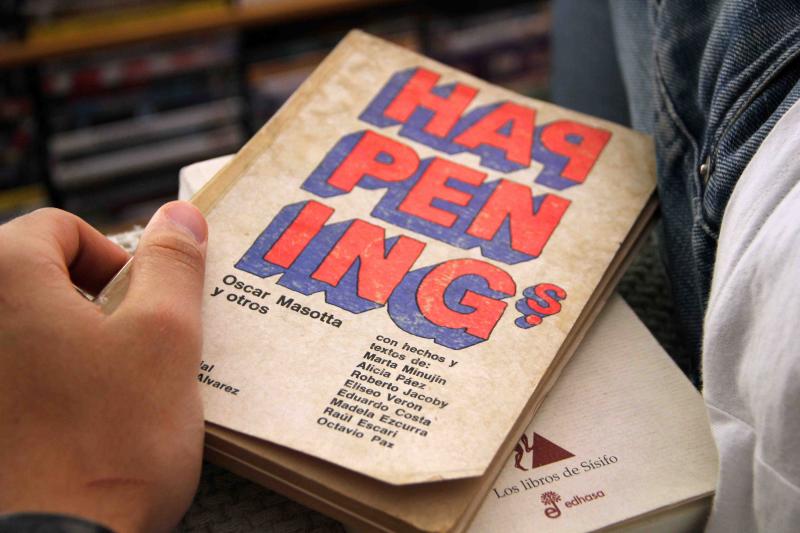

Image of a text by Oscar Masotta’s, “El Helicóptero”

Upon researching our project in Argentina, we later discovered the fascinating art practice of Oscar Masotta, who did two things in the early sixties. First, he single handedly introduced the writings of Lacan to a mass art audience, subsequently launching the industry we see there today. Second, he applied these Lacanian principles to his own art practice by way of conceiving the “anti-happening,” predicated upon the psychoanalytic principle that an utterance claiming that something happened was valid on it’s whether or not the event happened at all. Pushed to the extreme, perhaps the utterance is even more important than the event.

I think it’s uncanny how all this talk today of “fake news” resonates with Masotta’s “anti-happenings.” He wanted us to question if it happened to tangentially question the right-wing military accounts of daily events represented through news media. – Juli Carson

Masotta’s anti-happenings were examples of this. Specifically in the case of The Helicopter, of the two groups participating in the happening, only one group would have seen the helicopter, while the other group would experience it anecdotally from the first group. Did the helicopter happening really happen then? We don’t know. In that way, today we’re historically aligned with the second group. Masotta says it happened, so we presume it happened, even though there are only three easily constructed documents—which is to say rather sketchy documents—of the event: a picture of a distant helicopter, a play bill, and picture of visitors to the Anchorena train station.

I think it’s uncanny how all this talk today of “fake news” resonates with Masotta’s “anti-happenings.” He wanted us to question if it happened to tangentially question the right-wing military accounts of daily events represented through news media. We are struggling with that dilemma right now vis-à-vis Trump’s endless method of distraction by saying and tweeting spectacularly outrageous things. It’s even more prescient when you consider that today the current cover of Time Magazine asks: Is Truth Dead?

Alex: An interesting tie in to fake news, which feels especially chilling. So, how do these three issues connect in the digital film installation?

Bruce: Our parallel research projects will be tied together through our in-depth investigation tracing the effects of Masotta’s political, psychoanalytic, and aesthetic throughout the Southern and Northern Hemispheres. As a poetic means of approach this subject we are interested, metaphorically, in the convergence of migratory historical/cultural events and the glacier’s years of rupture.

Poetically speaking, Perito Moreno’s growth reverberates with the ruptures of history. But in Lacanian terms the manner in which it grows also echoes the operation of our unconscious drives. As described above Perito Moreno grows through a continuous flow of pressure, blockage, and fracture. This is also how Lacan describes the manner in which a subject’s desire grows. When considered together—the operation of the glacier, the operation of historical rupture, and the operation of subjectivity—a playful though serious platform arises upon which we can consider the vital exchange of nature and culture between the Northern and Southern hemispheres. The result is a non-hegemonic view of this relationship in political, aesthetic, and environmental terms.

The installation The Edge of the World at the Edge of the Earth premieres as part of a survey exhibition of Bruce Yonemoto’s work at Luckman Fine Arts, The Imaginary Line Around the Earth on view March 24 – May 13. Click here for more info on the exhibition.