Know Your Rights: A Tool for Artists

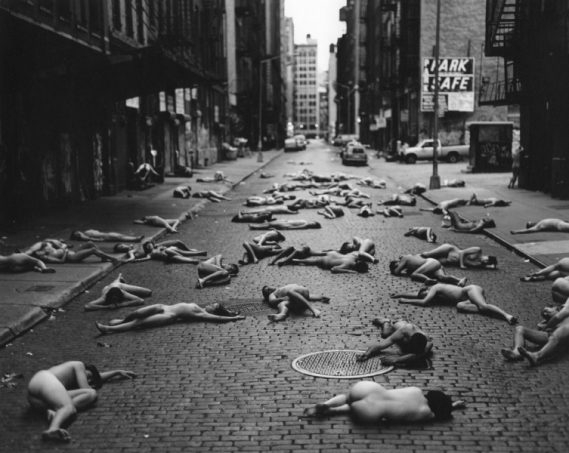

Spencer Tunick, Arrow To Washington, NYC, 1995. Gelatin silver print, 48×60 inches. Edition of 6.

We spoke with Joy Garnett from the Arts Advocacy Project at the National Coalition Against Censorship about a new artist education tool, Artist Rights.

Jenny Gill: How did the Artist Rights site come to be? Who compiled the resources and research available there?

Joy Garnett: Artist Rights was created to address questions that artists may have about their rights under the First Amendment. The site is a collaboration between the National Coalition Against Censorship (NCAC) and the Center for Democracy and Technology (CDT). Previously, NCAC put together an art law database with help from a lawyer and five law students, and the CDT had built a site to address artists’ online rights. The Artist Rights site brings together the content of these two resources into one cohesive, easily navigable site.

The impetus for creating Artist Rights was an incident involving an artist who received a letter demanding that their work, which included nudes, be removed from an exhibition in a public space. The letter contained legalese that the artist found confusing and intimidating; had he been able to penetrate the jargon, he might have realized that the assertions in the letter were incorrect and that he was well within his rights. And so the idea for the website was born.

Artist Rights offers answers to the many different questions artists may have about their rights, as well as a glossary of legal terms and examples of case law involving different forms of censorship with clear explanations for lay people. The idea is to make legal concepts and issues legible to ordinary people.

We’ve also set up a page with a form for questions and comments so that artists can contact us directly about potential controversies or issues they may already face.

It is important to emphasize that the Artist Rights site is intended as a quick reference tool and not as a stand-in for legal advice. While it provides basic information so artists can get a sense of some of their rights under the First Amendment, the information on the site is not a substitute for advice from a lawyer.

Jenny: How can artists use this site to answer questions about censorship and free speech?

Joy: The site is structured around four free speech and censorship issues:

- • protected vs. unprotected speech

- • speech regulated for its content or viewpoint

- • contracts

- • copyright and fair use

Artists can navigate through these categories using the site’s left sidebar, which contains drop-down menus.

For example, if an artist is worried that their work might be perceived as obscene or pornographic, they can click the drop-down menu under “protected vs. unprotected speech” and go to the section “obscenity & nudity”. There they will find the legal definitions for—and distinctions between—obscenity, pornography and nudity, and a list of links to relevant cases.

Another example: if an artist is selling their work in a public space and is told to shut down and move on, they can refer to the drop-down menu under “speech regulated for its content of viewpoint” and consult the “time, place and manner restrictions” or the “public forum” section.

Jenny: What about public performances or speech acts? What protection is there for artists who work in public spaces?

Joy: The government can regulate speech in public places up to a point. Here’s an excerpt from the public forum page, to clarify:

“A public forum is public property that historically has been associated with the exercise of First Amendment rights such as pamphleteering, public debate, and picketing. The public forum category includes streets, sidewalks, town meeting halls, and parks, among other locations. Because of the historic relationship between the public forum and free expression, the government cannot ban expression in a public forum. However, a public forum may be regulated by time, place, and manner restrictions as long as they are content-neutral, narrowly tailored to serve a significant government interest, and they leave open alternate channels of communication.”

Further down on that page is a list of links to relevant cases with brief descriptions. One of the cases listed, Tunick v. Safir, involves the photographer Spencer Tunick, who claimed that New York City shouldn’t be able to interfere with his photo shoot of 75-100 naked models on the grounds that it was part of a public showing of a work of art. When you click through, you come to a page with a longer, detailed description of the case, including any decisions and appeals:

“The court agreed that the city could not interfere with Tunick’s photo shoot because Tunick showed he would incur irreparable injury if he could not conduct the photo shoot and he was likely to succeed with his claim that this exhibition fell within one of the exceptions to the state law prohibiting public nudity.”

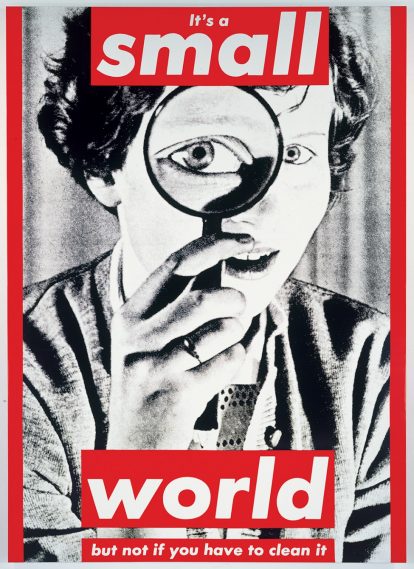

Barbara Kruger, Untitled (It’s a small world but not if you have to clean it), 1990. Photographic silkscreen on vinyl, Dimensions variable.

Jenny: Are there protections for works that contain parody or critique of a public figure, a brand, or other copyrighted material? What do artists who create this type of work need to be aware of to avoid a lawsuit?

Joy: Your question brings up two important but distinct issues. Parody necessarily references existing work; it is classified as a fair use and is a protected form of expression. A description of what may constitute a fair use can be found in an overview of copyright & fair use:

“Fair use is a statutory exemption to the rights granted by copyright law. It is a defense to activity that would otherwise be considered infringement. The doctrine permits the use of copyrighted works for many purposes, including scholarship, journalism, criticism, commentary, or parody (if the parody specifically criticizes or comments on the copyrighted work itself and not just on society in general).”

Public figures and their right to privacy is a separate issue, addressed in the section “privacy and publicity rights”:

“Artists cannot use a public figure’s image completely free of limitations. When the image is used for commercial gains, courts must balance the First-Amendment rights of the artist with the public figure’s publicity rights.”

An interesting instance of artistic expression trumping privacy rights is the 2002 case Hoepker v. Kruger:

“Hoepker, a German photographer, and his model sued Barbara Kruger for copyright infringement and invasion of privacy. Kruger, a well-known artist specializing in composite works combining photographs and texts, had taken Hoepker’s photograph of the model holding a magnifying glass over her eye, and superimposed the words “It’s a small world but not if you have to clean it” on top of it. With Kruger’s permission, the Museum of Contemporary Art L.A. and the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York (also defendants) publicized the exhibit in newsletters and brochures and featured the composite on postcards, note cubes, magnets and t-shirts and in exhibit catalogues.

“The Court found that the model’s right to privacy was not violated. To succeed on a right to privacy claim in New York, one must prove (1) the use of one’s name, portrait, picture, or voice; (2) for advertising purposes or for the purposes of trade; (3) without consent; and (4) within the state of New York. The Court found that Kruger had used Hoepker’s picture without consent within the state of New York but had not done so for the purposes of trade. Rather, Kruger’s work, when displayed in books or in galleries, was pure artistic expression (not commercial speech)…”

Jenny: Do you have any general advice for artists about free speech and anti-censorship rights? Is there anything they should know or do upfront that could help avoid censorship or legal action?

Joy: We’ve encountered many cases where artists will accept unfair and illegal demands without questioning them; these are usually instances where artists dare not risk pushing back for fear of the repercussions, such as having their work pulled from view. But artists should know that there are broad protections in place for artistic speech in this country. And government officials themselves are not always aware of the extent of these protections. So, to defend against ill-conceived, unwarranted, inadvertent or willful attempts at censorship, artists need to become more aware of their rights. The Artist Rights site is one resource they can use to inform themselves. They can also call us, or type in a question. We’re here, and we’re happy to help.

Joy Garnett is Arts Advocacy Program Associate at the National Coalition Against Censorship. Visit the Artist Rights website for more info: http://www.artistrights.info.